Crucial Changes Sprouting in Regional Cities

The distinguishing characteristics associated with Japan, the country and the society, go through dramatic permutations over time. In the 1980s, Japan was perceived as the nation boasting the world’s most rapid economic growth—as touted in Ezra Vogel’s book Japan as Number One—and as a high-tech wonderland. But Japan has changed much since then. Today it is distinguished, above all, by being the world’s most rapidly depopulating and aging society.

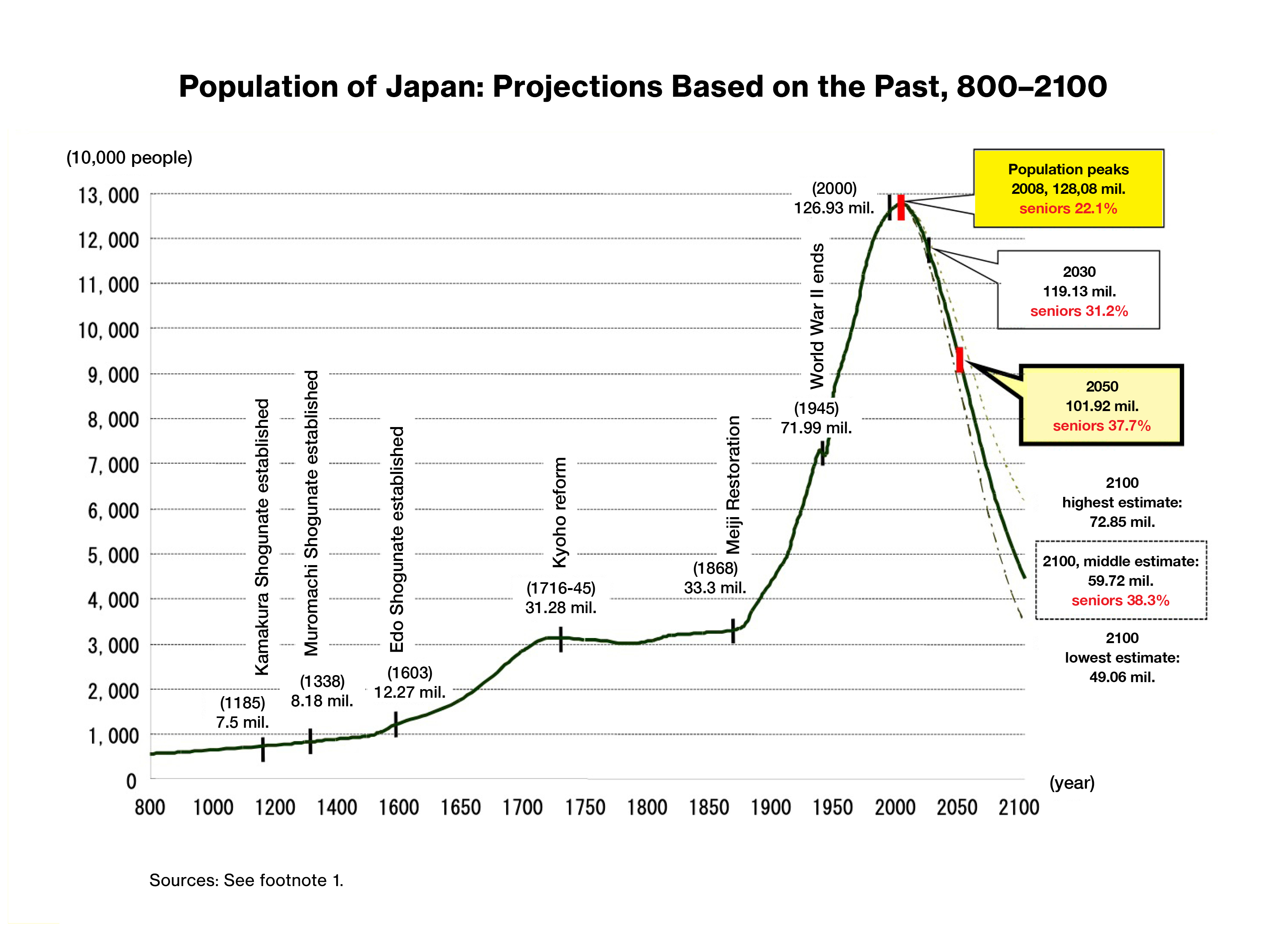

A look at long-term trends in Japan’s population reveals that it stabilized at around 30 million during the Edo period (1603–1867), then began a precipitous, nearly vertical climb after the Meiji Restoration of 1868. Since peaking in 2008, however, the population has steadily declined. If Japan’s fertility rate remains as low as it is now (1.36 in 2019), the population is forecast to fall below 100 million shortly after 2050 and to keep falling. The roller-coaster-like curve suggests that Japanese society is entering a phase unlike any it has ever experienced before.

On top of that, Japan is also at the forefront of the aging trend among the world’s nations. In 2020 the country’s aging rate (the percentage of the population aged 65 or older) stood at 28.7%, making it “number one” in the world. The current forecast is for Japan to maintain this front-runner status until at least 2060.

What sort of impact will these two trends—depopulation and aging—have on the physical and spatial configuration of Japanese society? Two effects come to mind.

The first will be on the relationship between Japan’s metropolises—notably Tokyo—and its regional cities, towns, and villages. The era of continual population growth was marked by a relentless flow of bodies in the direction of Tokyo. Millions of people, particularly of the younger generation, moved from the villages to regional cities and thence to the capital. This was accompanied by the increased concentration of political and economic power in Tokyo as well. The result was a rapid hollowing-out of Japan’s outlying cities that turned their downtown shopping districts into what became known as “shuttered streets." A contributing factor was the Japanese government’s post-boom policy of promoting the development of suburban shopping malls sustained by a roads-and-cars lifestyle based on the American model.

The main street of Wakayama city (population approx. 370,000) shows a typical condition of Japanese regional cities today, where the main shopping streets are becoming so-called “shuttered streets.” Photo by the author

The main street of Imabari city (population approx. 160,000). In addition to smaller cities (pop. less than 20,000), larger cities (pop. 300,000-400,000) are also being hollowed out. Photo by the author

More or less concurrent with the outset of Japan’s population decline in 2008, however, people’s values underwent a shift. In a reversal of the trend up to that point, they began leaving Tokyo for other parts of the country, as well as exhibiting a more “local” orientation. The prevailing perception of residence in Tokyo as an absolute positive gave way to a more favorable view of life in the provinces. This tendency is evident among students and other young people I meet. It will be very interesting to see how it evolves in the future, as well as what changes will occur in regional cities and towns around Japan.

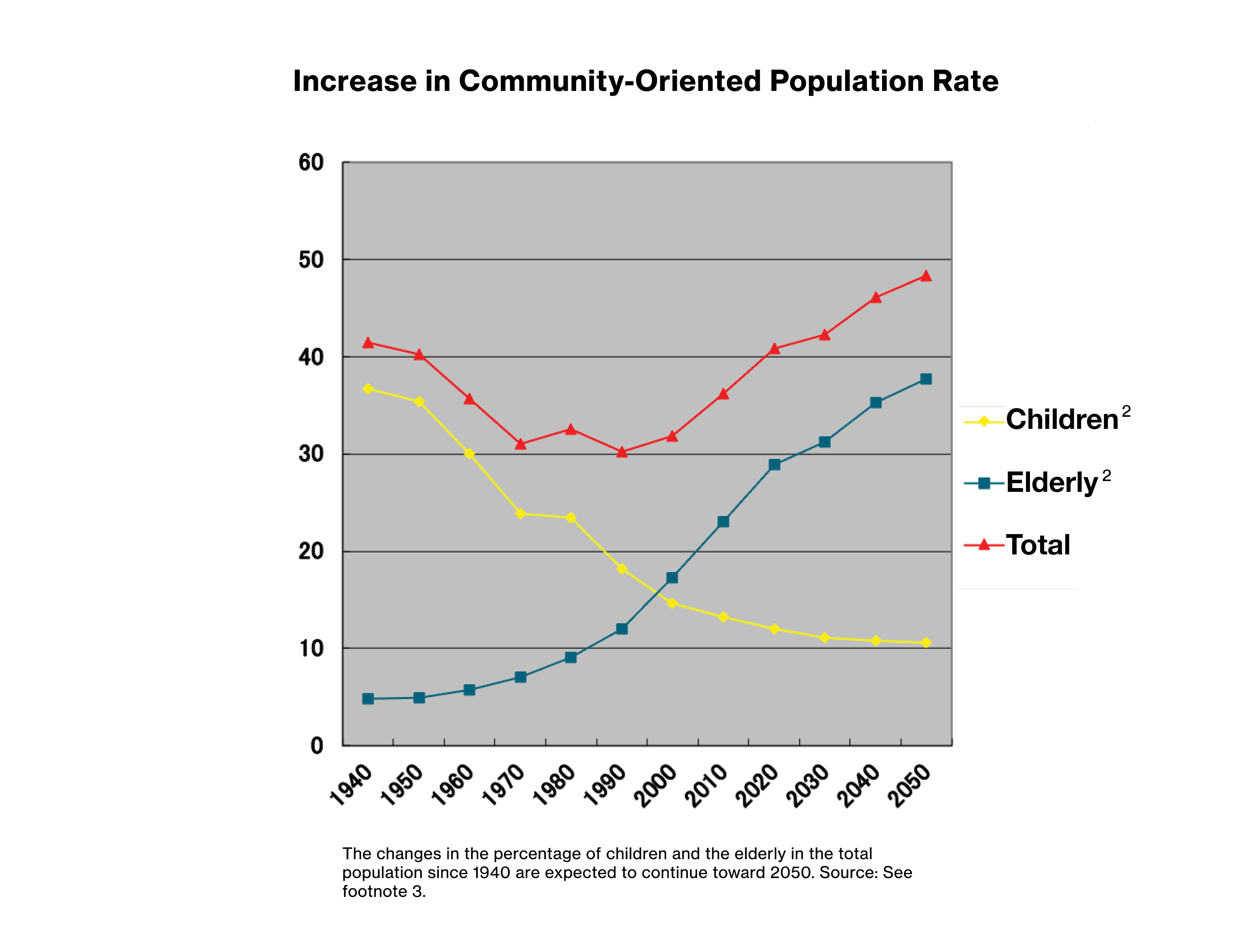

The graph below shows the changes from 1940 to 2050 in the percentages of children and elderly out of the entire population. The percentage of children has continued to decrease while the percentage of elderly increases. Of particular interest is the cumulative percentage of children plus the elderly, which I call the “community-oriented population rate.”

The second effect of the depopulation and aging trends will be an increase in the community-oriented population of localities around the country. Children and the aged are more closely connected to and dependent on their community than people at other stages of the life cycle. Hence the percentage of the population composed of these age groups is of great significance to communities.

As the graph shows, changes in this community-oriented population rate form a shallow U-shaped curve. The rate declined while Japan’s population was growing, but now it is rising—primarily due to the growing number of elderly—even as the overall population decreases. What this means for the Japan of the future is that ties between individuals and their community will become closer, and the importance of the communities that support these populations will inevitably grow.

Today we see many elderly people for whom it is a daunting challenge to take care of their shopping needs because it entails driving a car to a distant mall. The risk of getting in a traffic accident is also high for this age group. Meanwhile, the coincident trends of aging and depopulation in Japan have caused a surge in the number of single-person households, dooming many people to a life of isolation and loneliness. Sadly, the World Values Survey indicates that contemporary Japanese society suffers from the highest degree of social isolation among the developed nations.

Yet this situation—and the aging of our society in particular—also offers us a golden opportunity to design cities and towns that prioritize local community spaces and pleasant, walkable living environments. Indeed, it is crucial that we do so. The creation of new kinds of community that meet the changing needs of our era is the biggest challenge facing Japanese society today and tomorrow.

Sources: compiled by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, based on the population census, the population estimates, and the intercensal adjustment of current population estimates (2000–2005), all taken by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. The population projects for Japan (2006–2055) and the outline of results, methods, and assumptions were done by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, and the long-term time-series analysis of population distribution change in the Japanese archipelago (1974) was carried out by the National Land Agency.

“Children” are under 15 years old. “Elderly” are 65 years old or older.

Source: compiled by the author based on the national census up to 2010 and the “Future Population Projections for Japan” (2017 estimate) for 2020 and beyond.