Alone Again, Or: Two projects exploring life in Tokyo’s evolving fabric

Mohsen Mostafavi: Kuma-san, I’m really happy that you’re here to talk with us about the future of urbanization in Japan. I know that you care deeply about architecture, the way in which architecture happens in Japan, and the relationship to site. Can you explain in more detail your position in relation to architectural ideas, the role of materials, and the role of tradition?

Kengo Kuma: To begin, I want to say a word about the older generation—Ando-san, Ito-san, that generation. They were born in the 1940s, and I was born in 1954. So there’s a ten-year gap between us. For Ando-san’s generation—including Isozaki-san and Kurokawa-san [born in the 1930s]—there were two schools in Japan: modernism and tradition. On the tradition side, there was Togo Murano, Isoya Yoshida, and Junzo Yoshimura, and modernism was the total opposite. These two schools were directing two different cultures and two different philosophies in Japan.

Kengo Kuma, Nezu Museum, Tokyo, 2009. External passage under eaves. Photo: FUJITSUKA Mitsumasa

Kengo Kuma, Nezu Museum, Tokyo, 2009. Gallery looking toward the garden. Photo: FUJITSUKA Mitsumasa

For me, the border between tradition and modernism makes no sense. I see no different philosophy, no different method, no different material. Whether it is tradition or modernism, it is basically just designing the city. I often use traditional vocabulary, including the hisashi, long eaves and screens, and material-wise, I often use traditional materials as an important protagonist for the project. This design method is very different from the one used by the older generation.

Sometimes Maki-san and Kurokawa-san used the reference of traditional design but as an abstraction. They tried to transform traditional design and translate it to contemporary design, with a totally different look. They were trying to avoid similarity as much as possible. But I’m not afraid. Similarity is not a problem. This is my attitude, both for singular buildings and for urban design. In urban design, I am trying to bring back Japanese street culture—narrow streets, intimate streets covered by hisashi—and maybe semi-outdoor spaces as well. We try to bring that urban design to contemporary urban design.

Mohsen Mostafavi: I want to ask you about this relationship between modernity and tradition but also about your own history. In Japan, I think people often have a particular lineage. For example, Ito-san worked with Kikutake-san and also had a close relationship with Mr. Shinohara, and these are two quite different contexts between Kikutake and Shinohara. How did you develop your interest and your commitment to this idea of not having a clear boundary between modernity and tradition? What was the formation of your ideas?

Kengo Kuma: I had two mentors at the University of Tokyo. One was Hiroshi Hara, who at the time was doing research on villages in Africa, South America, and the Middle East. This was very new for me because the design did not belong to traditional Japanese buildings or to modernism. I accompanied Hara-sensei to the Sahara Desert and found that the villages had a warmth, a naturalness…and the geometry of those buildings was very different from traditional Japanese villages. So that was one influence.

Kengo Kuma (at right) during the research into Saharan desert villages led by Hiroshi Hara in 1979. Photo courtesy of Kengo Kuma & Associates

My other mentor at the University of Tokyo was Professor Uchida, who taught construction methods, everything from traditional Japanese construction to contemporary construction, including Buckminster Fuller. Professor Uchida knew Buckminster Fuller personally, and as Uchida-san taught me, the open system of Buckminster Fuller’s buildings had some similarity to the Japanese open system. I was very inspired by that comment.

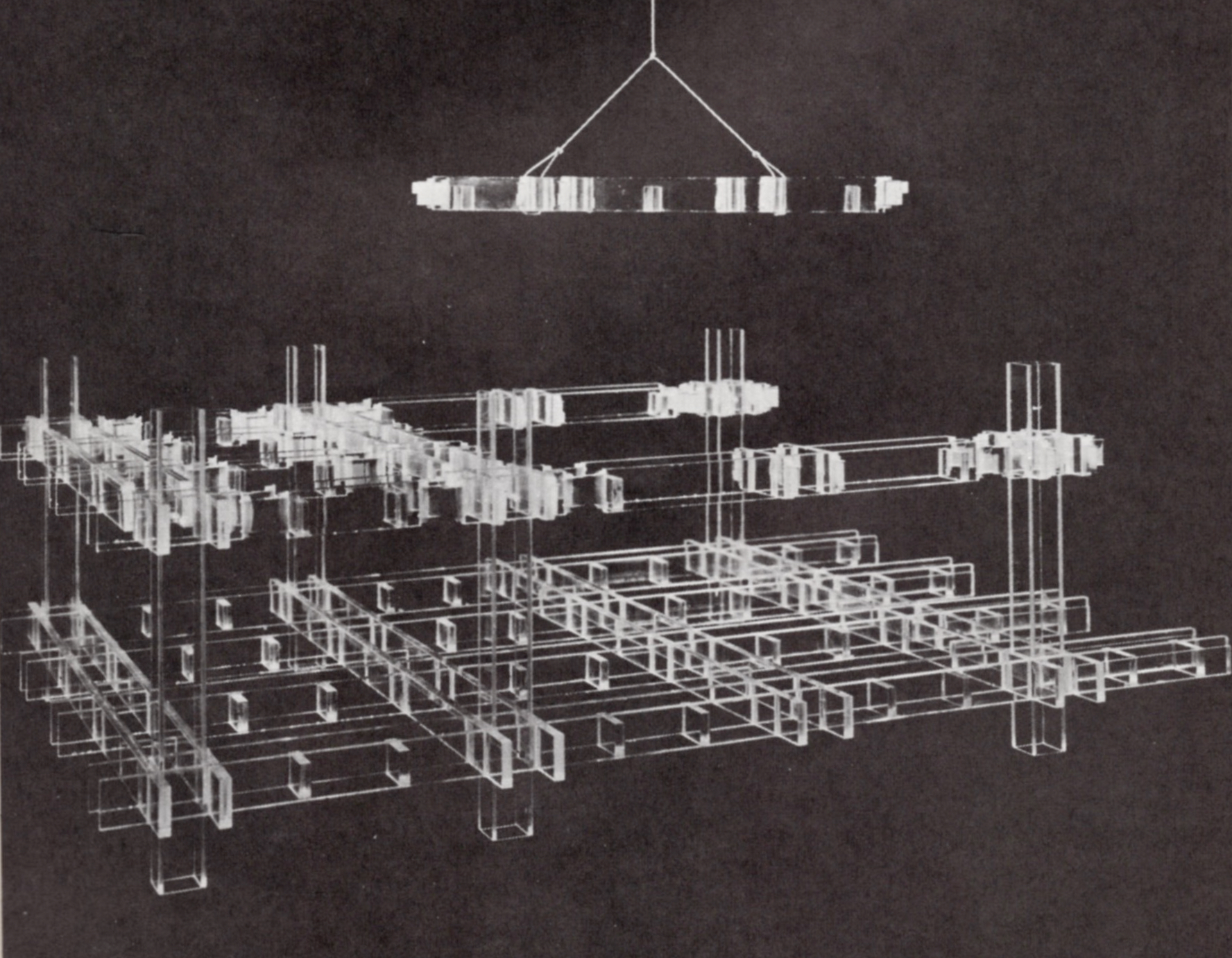

Yoshichika Uchida, director, A Project of Prefabrication System for “BOX-UNIT HOUSING” by Uchida Laboratory, The University of Tokyo (GUP-VII PROJECT). The photo shows a part of the process of assembling an industrialized housing unit. Published in Kenchiku Bunka (April 1972)

Mohsen Mostafavi: So, on the one hand, there is this tension between modernity and tradition. On the other hand, you also have very specific ideas about the role of what you call the anti-object, of architecture as something that—whether through its materials or through its making—has a relationship to the environment, to a site. Do these ideas come from your collaboration with Professor Uchida and Professor Hara? Or is that something that evolved later? Can you also speak about this relationship of architecture to a site or a location or a situation?

Kengo Kuma: The basis of my philosophy of the anti-object came from Hara and Uchida. But I didn’t use the word “anti-object” until the 1980s, when I started my own practice. At the time, postmodernism was still very influential. Japan was in the bubble era and people wanted monumental, unique buildings. I hated those monumental concrete buildings, so I began to write about the anti-object. But during that period, I still couldn’t find my own design, my vocabulary. There was just a kind of criticism, and in my frustration, I began to write books. Through writing, I slowly found my way to a new kind of design, totally different from those monumental buildings.

Mohsen Mostafavi: In terms of your writing or your thinking, when did you first become interested in urbanism, in the relationship of the architectural project to something bigger than just its site?

Kengo Kuma: I think it was in the early 1990s. Every project in Tokyo was canceled when the bubble burst. And so I had time to travel to the countryside of Japan, and luckily I received a commission for a small project in Yusuhara, a town in Kochi Prefecture. It is very remote, with a population of only 8,000 people. But over the next 30 years, I designed six buildings in Yusuhara. And through the experience in Yusuhara, I came to feel the big potential of small villages in Japan.

In these small villages, there are no traffic jams, and people enjoy a peaceful life, surrounded by nature. Craftsmanship still survives in those towns. And I could design building by building and think about the relationship between the buildings. I could design the space between the buildings as well. So my interest in urban design started in Yusuhara. Afterwards I applied those methods to the big city.

Kengo Kuma, Yusuhara Town Hall, 2006. Photo: FUJITSUKA Mitsumasa

Kengo Kuma, Community Market Yusuhara, 2010. Photo: ©2010 Takumi Ota

Kengo Kuma, Yusuhara Wooden Bridge Museum, 2010. Photo: ©2010 Takumi Ota

Kengo Kuma, Yusuhara Community Library, 2018. Photo: ©Kawasumi • Kobayashi Kenji Photograph Office

I think the most important urban design for me is Nagaoka City Hall. Nagaoka is a typical rural city with a population of 280,000. It used to have a very intense, active city center, but all that disappeared as people began to rely more and more on vehicles to get to the big shopping center and the big museum on the outskirts of the city. I designed a community plaza that connects with City Hall in Nagaoka. It is a very successful project because the plaza has become a magnet for the people of Nagaoka, and now more than one million people gather in the city center every year.

Kengo Kuma, Nagaoka City Hall Aore Nagaoka, 2012. Assembly hall. Photo: FUJITSUKA Mitsumasa

Kengo Kuma, Nagaoka City Hall Aore Nagaoka, 2012. Roofed plaza. Photo: FUJITSUKA Mitsumasa

The method for the plaza in Nagaoka came from Yusuhara, using local materials and taking special care with the materiality of the floor. Instead of granite pavement or ceramic tile, we used rammed earth, a very soft material that is typical for farmhouses and narrow streets in Japan. And we brought this soft materiality to the plaza in the city.

In this way, my ideas were gradually realized. At first, I worked in very remote places, but slowly I moved from Yusuhara in the early 1990s to Nagaoka in 2005 and then to Tokyo and the center of Japan. And finally in 2019 I, along with Taisei Corporation and Azusa Sekkei, realized the national stadium, officially named the Japan National Stadium, one of the main venues of the Olympic games in Tokyo in 2021.

Mohsen Mostafavi: I’m glad you mentioned the Olympics because one of the things that we’re studying is the way in which Japanese urban development goes through a series of interruptions, for example, the war and the bubble economy. But also you have phenomena like the Olympics, which Japan first organized in 1940 (although that Olympics didn’t happen) and then the 1964 Olympics, which had a big impact on Tokyo with the development of many highways, the widening of streets, really the creation of parks and public spaces to some degree.

Did this history of the Olympics play any role in your thinking for the design of the stadium? And what role do you think the 2020 Olympics plays in urbanization in terms of transforming Tokyo beyond the stadium itself?

Kengo Kuma: The 1964 Olympic Games were very important for the country because before 1964 people were just working hard to build their own house with a TV and a big fridge and that kind of American lifestyle. That was the goal of the Japanese before the 1964 Olympics. But in 1964 people began to ask themselves, what is Japan? What should be the culture of Japan? And Kenzo Tange showed us a very beautiful answer to that question. His Yoyogi Stadium is the symbol of Japanese culture after the Second World War.

For the 2020 Olympics I want to do the same thing. I want to show the new image of Japan as we face many problems, including the declining birth rate, the aging society, and the economic downturn. Even with these difficulties, we should find happiness, the kind of happiness that exists in nature in Japan. Wood can be the symbol of the new Japan, and we used wood as a protagonist in the stadium.

Mohsen Mostafavi: How do you think your audience, people who visit the building, will understand the symbolism of the building? How will the building communicate to them these qualities that you mentioned?

Kengo Kuma: For Kenzo Tange’s Yoyogi, the symbolism is very much related to the beautiful silhouette of the building, which can be seen from afar. The two towers and the curvature between them is a very monumental gesture toward the city. Our stadium, by contrast, is basically flat: we dropped the height of the stadium as much as possible. In Zaha’s scheme, the first scheme, the height was about 70 meters at the top. The highest point in our stadium is about 47 meters from the ground, much lower.

We also want to use the same material throughout the stadium. The gesture is very subtle, but people can feel the wind, which flows under and inside the stadium, as well as the warm material in the eaves around the exterior of the stadium. Kenzo Tange’s gestures and the gesture of our stadium are totally opposite. We want to show the contrast between two attitudes.

Mohsen Mostafavi: Many of the qualities you’re discussing have to do with the experience, they’re experiential qualities—the wood, the wind, the scale. And you mentioned the reduction in scale. I know Maki-san was very much in favor of making a smaller building on this site. Do you think this modesty is also an important quality of the stadium?

Kengo Kuma: I totally agree with Maki-san’s allowance for modesty. But the reality is that a contemporary national stadium needs a big space for TV, a big space for sponsors, and we should have that floor area. Maki-san ignored this reality. We tried to make the impression of the building as low and as small as possible and that is our attitude.

Mohsen Mostafavi: Let’s continue the conversation about the relationship of architecture to the city. You’ve also written about new forms of development in the city. In Tokyo, for example, there are a few large-scale developers—companies like Mori Building, Mitsui Fudosan, Mitsubishi Estate—that have a great deal of influence in shaping this city. They maintain a very close relationship with certain parts of Tokyo, and they’ve been developing those areas for a long time.

Tokyo seems to be evolving not through its neighborhoods, not through its communities, but really through these large-scale developments like Roppongi Hills and Tokyo Midtown. Now we have the Nihonbashi area. What are your thoughts about the nature of large-scale development in the city? Are there pros and cons?

Kengo Kuma: Those developers are very well connected with government, and for those big developments—Roppongi Hills, Tokyo Midtown—they got a lot of government support that allowed them to gain bonus floor area. It is unavoidable, but the bonus floor area really isolates a development from its neighbors. The context of Tokyo is based on the Edo system—it’s a narrow street and small greens—but those mega-scale developments are islands totally separated from their context. Economically, it was necessary, but in terms of urban design, it is a tragedy for Tokyo.

Mohsen Mostafavi: But you worked on Tokyo Midtown and participated in that project. So I’m curious, based on your experience and the critique that you just made, what are your thoughts about how the city should develop?

Kengo Kuma: We should find a new way of development, not like Midtown and Roppongi Hills. Continuity with the context, continuity with the existing street system, is very important for Tokyo. Currently we are advising on the urban design for the Takanawa area and really trying to show the new model for urban design based on the street and also recovering the connectivity to the city. I think that some people from the government understand those ideas, and I am not so pessimistic about the future of Tokyo.

Mohsen Mostafavi: You’ve been involved in Shinagawa station and the Shibuya development. What do you think about the role of the railway companies as developers and the way that railway stations are really also providing new forms of public space in the city? What’s the difference between a development done by the railway company and one done by the big developers?

Kengo Kuma: There are big differences. The big developers buy the land themselves, and the land is very expensive. By contrast, the railway companies already own the land and haven’t been using it for many years. Recently they realized that there is a potential for the linear land they own adjacent to the railway, and our Shinagawa project uses those linear spaces adjacent to the railway. It is a totally different site and a totally different economic condition. There is big potential in the railway company.

Kengo Kuma, Takanawa Gateway Station, Tokyo, 2020. The complex facility is designed to work as a nexus for the surrounding areas as well as a new gate to Tokyo. Photo: © East Japan Railway Company