Alone Again, Or: Two projects exploring life in Tokyo’s evolving fabric

Mohsen Mostafavi: I know that you have devoted a good part of your career to studying the question of aging, especially in the Japanese context. Could you tell us some of the key characteristics of Japan’s super-aging population and how the Japanese condition differs from that in other countries?

Hiroko Akiyama: Currently, Japan is going through a major transition toward the era of 100-year life spans. New ways of living are starting, and the society is being reorganized. For several centuries, up to the mid-20th century, 50 years was considered to be the typical life span in the country. But life expectancy increased rapidly during the latter half of the 20th century, and now we are talking about a 100-year life span.

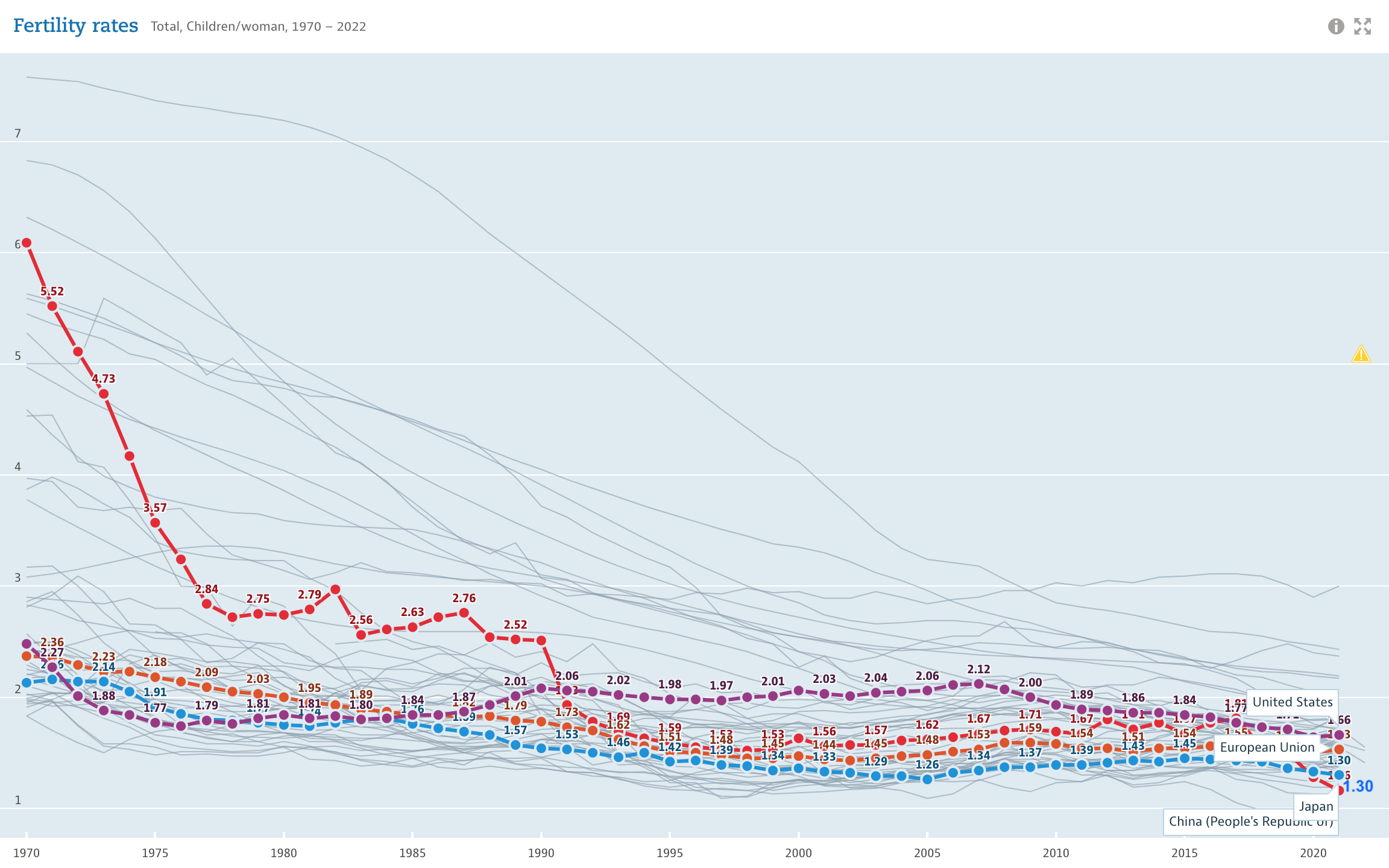

Fertility rates, 1970-2022.

Source: OECD (2024), Fertility rates (indicator). doi: 10.1787/8272fb01-en (Accessed on 10 April 2024)

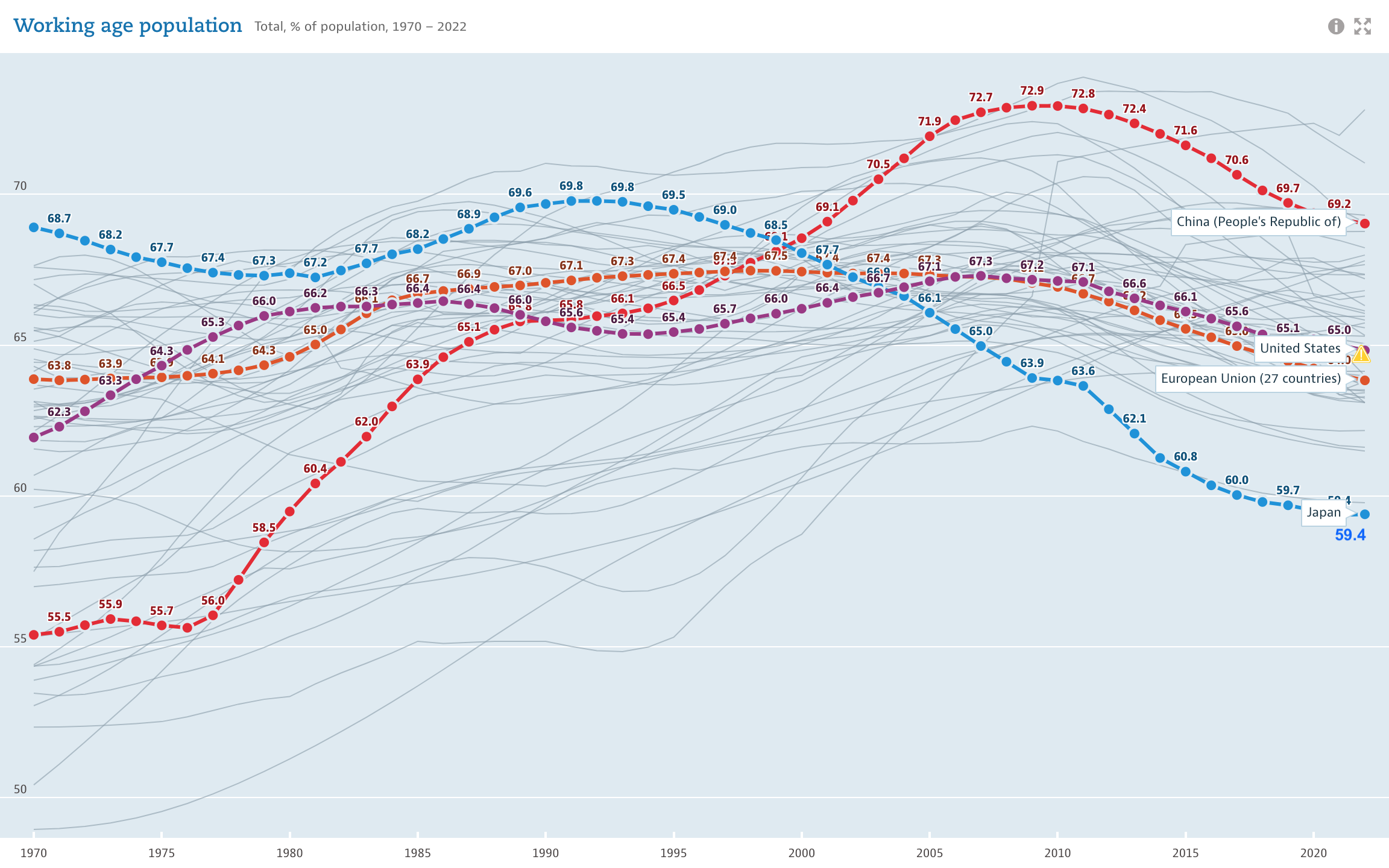

Working-age population, 1970-2022.

Source: OECD (2024), Working age population (indicator). doi: 10.1787/d339918b-en (Accessed on 10 April 2024)

What complicates this situation is the low fertility rate, which is 1.30.1 And this is a big factor in the shrinking of the total population, which started in 2008, and the decrease in the working-age population. Our question is, how should we approach these challenges in a society of 100-year life expectancy, which no one has experienced?

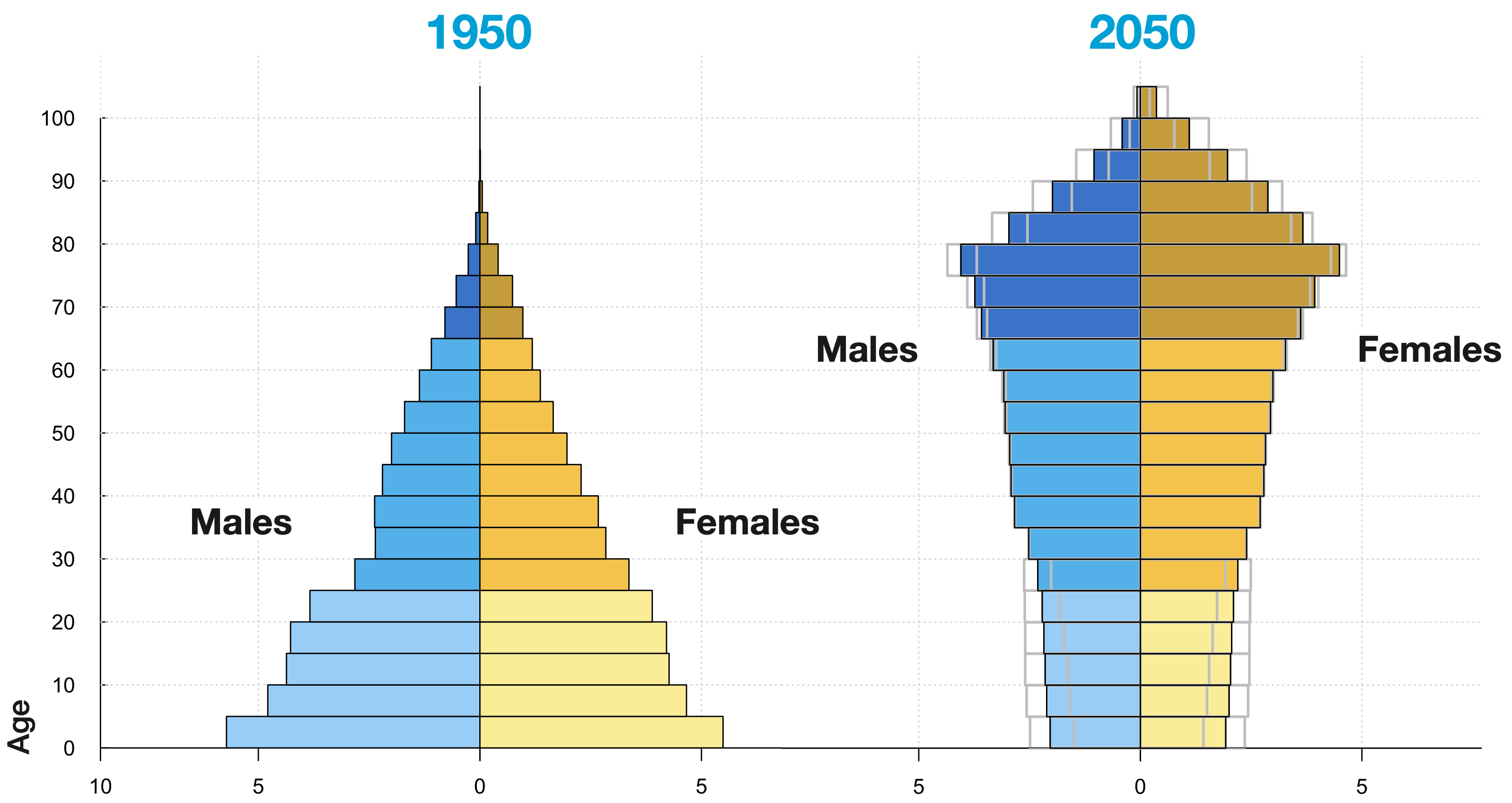

Mohsen Mostafavi: I understand that roughly a third of Japan’s population is over 65 years old at the moment, which makes the country a “super-aging society.”2 Am I right?

Hiroko Akiyama: Right. To be precise, 28.8 percent of the population,3 so nearly 30 percent, is over 65 years old currently. The figure will reach one-third of the population by the year 2030.

Mohsen Mostafavi: How does that compare to the US or European countries, for example?

Hiroko Akiyama: I think the figure in the US is about 17 percent. But every country in the world, including the countries in Africa, has an aging population. It’s just that the speed of aging is different, and there is some time lapse. In five to ten years some other countries will be in the same condition as Japan is now. Aging is a global issue—it’s not only about industrialized countries.

Population pyramids of Japan, 1950 and 2050.

Sources: Source: © 2019 United Nations, DESA, Population Division. Licensed under Creative Commons license CC BY 3.0 IGO. United Nations, DESA, Population Division. World Population Projects 2019, Volume II: Demographic Profiles. 2

Mohsen Mostafavi: Are there any significant changes that are happening in Japan in terms of family structure?

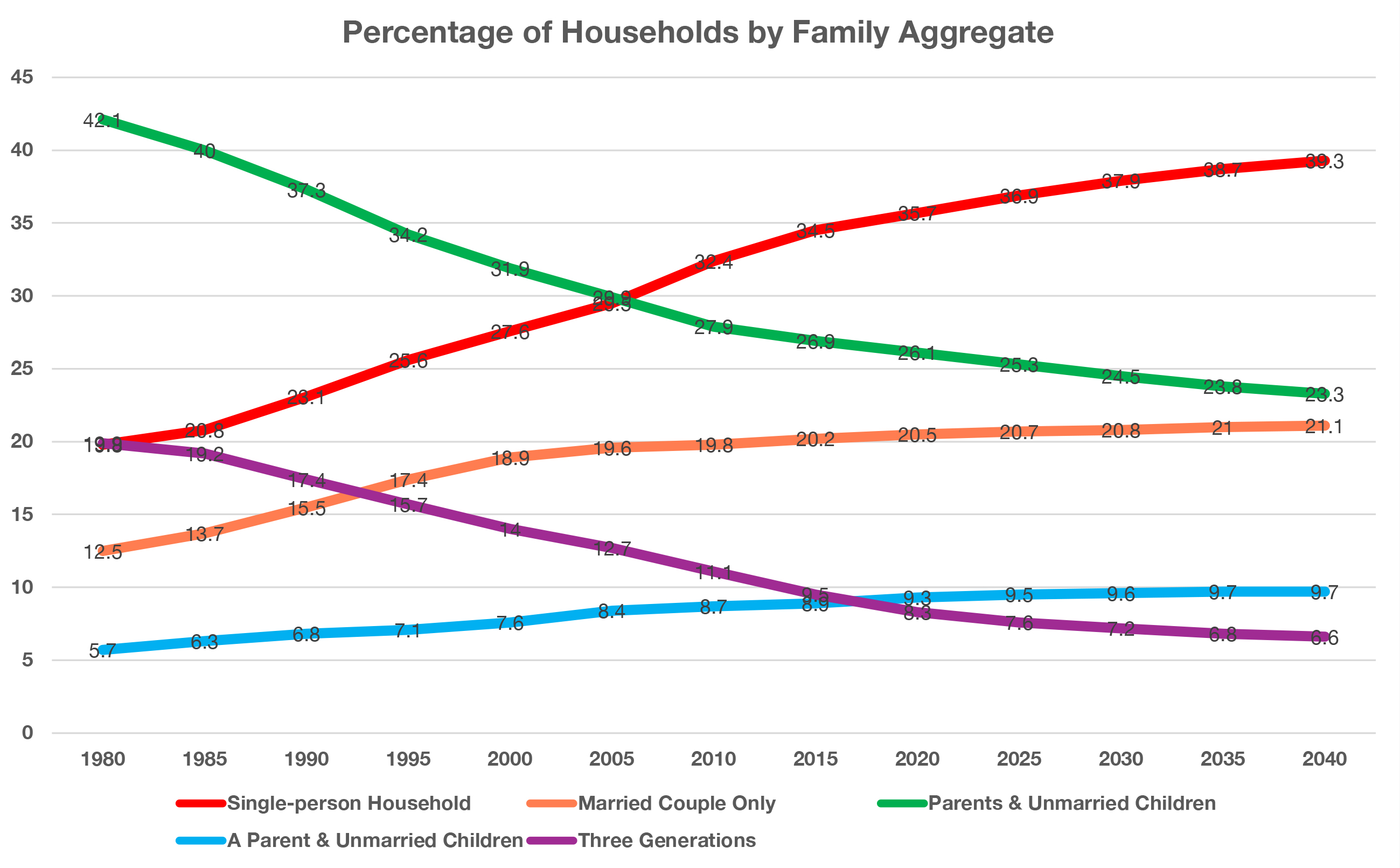

Hiroko Akiyama: Yes, there is a big change. The typical elderly household in Japan today is just a husband and a wife, or a single person. Three- or four-generational family households comprise about 30 percent or less of the total number of households. It’s quite different from 50 years ago, when the three-generation family was the typical household type and the majority of elderly people lived with their children’s family.

Percentage of households by family aggregate in Japan, 1980-2040.

Source: Equality Bureau, Cabinet Office (Accessed on 10 April 2024)

Mohsen Mostafavi: What is your prediction of what might happen in the next 20 to 30 years?

Hiroko Akiyama: I think we’re going to see the current trend of elderly people living alone or with a spouse will only accelerate, especially since they want to live independently from their children. That’s the choice they make.

Mohsen Mostafavi: So a large portion of the population—and many of them are a couple or one person—would be reasonably healthy and are going to live longer. What seems to be really critical is people who are reasonably healthy but alone: people who need some level of sociability and assistance though they don’t need to be in a nursing home. I know there are the elderly people who are pushed to the periphery of the city, who are living alone in slightly more difficult circumstances, or who are not able to take care of themselves. Are there any specific patterns that you have observed about such people?

Hiroko Akiyama: A large portion of the elderly population in poverty are single women, who lost their husbands or lived single for their entire life. In terms of social isolation, an equally critical pattern is single men who lost their spouses: they might be well-off in terms of money but they could be socially isolated, having no social network.

Mohsen Mostafavi: So you have to find a way to put them together.

Hiroko Akiyama: Right, yes! [laughter]

Mohsen Mostafavi: I have a friend whose father was in a nursing home where he was able to find female friends even though, sadly, they passed away one after the other. Finding a new partner can obviously be a very important part of the future of super-aging society. You need places where you can meet and socialize.

Hiroko Akiyama: Yes. Now there is matching business for seniors. Going back to your question, a large portion of the poor elderly are women, yet over 90 percent of elderly people own their house. So they stay there with a small income until reaching an almost extreme situation and then they move to a public nursing home. That is the typical pattern of poor people, both men and women.

Mohsen Mostafavi: The statistic that you give on homeownership seems unusually high.

Mohsen Mostafavi: What sort of environment would be the most productive and inspiring for that part of the population? I think that could be an important issue for the future of the city.

Hiroko Akiyama: I agree. In the big picture, we need to redesign the existing infrastructures of Japanese cities, both in terms of hardware and software, in order to meet the needs of the aging society. The existing infrastructures were built when the population was much younger. But now we have to rebuild cities to accommodate people who can live for 100 years, staying healthy, active, connected, and having a sense of security. That’s the overview of what we are working on.

Mohsen Mostafavi: Which brings us to what you are undertaking at the Institute of Gerontology at the University of Tokyo. I’m interested in research at the institute in terms of the spatial or urban dimension of aging. Can you tell us about the current activities and the key issues of research at the institute?

Hiroko Akiyama: First of all, gerontology is a multidisciplinary field of science: it overarches medicine, economics, engineering, and education, among others, and there are different issues in each area. The major role of the institute is to make a network of scholars and researchers in those fields, who work with towns, for example, as a means of changing the society.

We solve social issues together. We call it “action research.” We have chosen two communities to work with: the city of Kashiwa4 as the urban site and the city of Fukui as the rural site. There are a lot of common yet different issues in the rural and urban domains.

In Kashiwa, for example, we are working on several projects at the same time to address the needs of the highly aged society. One of the projects is about mobility, which is a big social issue in an aging society. A team of professors in the schools of mechanical engineering, physiology, and law works with automobile companies such as Toyota, the local government, the national government, and the citizens. They all work together to change the transportation system in the city. It’s a kind of intervention research, which we evaluate ourselves. It’s different from science-science research.

Mohsen Mostafavi: That’s brilliant.

Hiroko Akiyama: But we also need to overhaul and change the long-term health care system, which is another big project in Kashiwa. Scholars from the schools of medicine, engineering, and economics, among others, collaborate on this project. They design, create, and put things into practice, then evaluate the system. And based on the outcome of this process, they make a policy recommendation with scientific evidence.

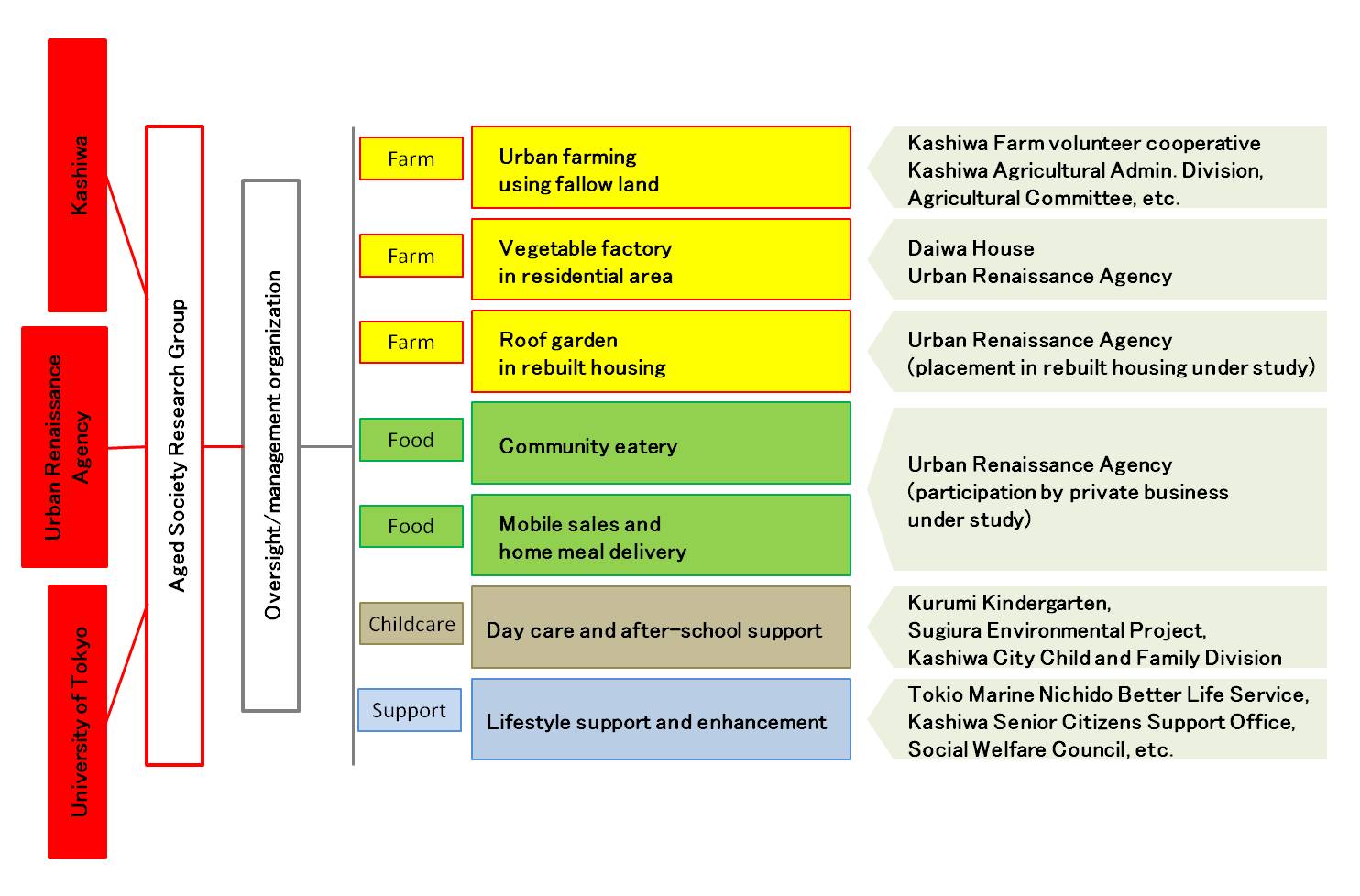

Community for 2030, an “age-in-place” project pursued by the Institute of Gerontology in collaboration with Kashiwa City and the Urban Renaissance Agency, to turn the rapidly aging neighborhood into a senior-friendly community with medical and nursing facilities and workplaces for the elderly.

© The Institute of Gerontology, the University of Tokyo (Accessed on 10 April 2024)

Organization structure for creating workplaces for the elderly in Kashiwa.

© The Institute of Gerontology, the University of Tokyo (Accessed on 10 April 2024)

Mohsen Mostafavi: That’s great.

Hiroko Akiyama: We work with the vision called “Aging in Place.” I believe the concept started in the United States, but it’s also consistent with the Japanese government’s policy of enhancing community-based health and social care (chiiki hokatsu kea). They are pushing hard to enable people to stay in place and live there as long as they wish. The program under the policy provides healthcare, including medical care and social care services, delivered to the home.

Mohsen Mostafavi: Delivered to the existing home?

Hiroko Akiyama: Yes, to their own home. They make a team of a physician, a visiting nurse, a visiting home helper, and so on. They provide professional care as a team and social care services such as transport, the so-called meals on wheels, and other kinds of service. They also create jobs for elderly persons to have a role and engage in the society and feel they are valued.

Part of my work in Kashiwa was to make a workplace for life’s second act. We created a number of jobs in places where people can walk or ride bikes from home. We also created a flexible scheme of working. Since elderly people are diverse in terms of physical strength, when they have free time, what kind of lifestyle or value system they have, we needed to allow them to choose when and how long they want to work.

The opportunity we created can be a lifelong engagement, a lifelong learning opportunity, and an arena for socializing. The place we created is for everyone—not only elderly people but children and working-age people—to be engaged in the society.

Mohsen Mostafavi: It sounds very inspiring.

Mohsen Mostafavi: At the beginning, you mentioned that super-aging and the low birth rate are occurring at the same time and, as a result, the population is declining. I think there is also a slightly more controversial topic, which is the labor force and immigration. Japan will have fewer people, living longer, and a smaller workforce: there needs to be a different economics, which is to create pensions for an increasing number of people based on the labor of fewer people.

I wonder how immigration might kick in with the challenges of labor shortage along with depopulation, super-aging, and low birth rate. It seems that these factors together form rather a complex landscape in Japan. Among the people in your field, is there any specific opinion about the mixing together of all these elements and its consequence on aging?

Hiroko Akiyama: Well, to face the challenge of working-age population decrease, we have to come up with a good solution to build a sustainable society. We are working on several solutions. One, which is the first priority, is to raise women’s labor force participation, which has been relatively low. To do that, it’s necessary to create an environment where both young men and women can work and raise children at the same time.

The second is to make the workplace age-friendly. The current generation of seniors are healthier, better educated, and more willing to work compared to the previous generations. We need to develop a scheme for seniors as well as people with disabilities to be able to join the labor force within their capacities, so that each and every person can contribute to the society for their entire life. That is what we are pushing.

Another challenge is immigration. Japan is gradually opening up the labor market to other countries, especially due to the shortage of care workers. This is a common situation among all the OECD countries. Typically, Japan has young workers from the Philippines and Indonesia who take care of the elderly in nursing homes. But their own home countries are going through the same process of aging. So, in terms of care services, I don’t think relying on immigrant workers will be the ultimate solution. We must use technology, for example, which I believe has pretty good possibilities.

Mohsen Mostafavi: Right. What you are saying also relates to the economics of care and the economics of aging from perspectives of both the state and the individual. Let’s say people used to have a life expectancy of 55 or 60 years, whereas now you’re moving toward 100 years in Japan. What are the repercussions in terms of personal savings, the way people live, and how they can survive?

This question is about the financial component of sustainability, which requires some level of support from the government, but presumably some of the burden will also be on the individual. I’m wondering how the dynamics of the economics of aging is changing and how it might change in the next 20 or 30 years. Will the government need to invest more and more in this area? Where will the money come from?

Hiroko Akiyama: On the individual level, elderly people today live on pensions and social security. There is national health care insurance and long-term care insurance. So these costs are covered by national insurance, to which the elderly have contributed. Poverty does exist, but the majority of the elderly are not really struggling financially. Even if they need care for being bedridden, they don’t need to worry about money. The copayment for people over 75 years old, for example, is only 10 percent of the total cost.

But we’re not sure about the future. Baby boomers are now turning 75, and the total cost of their medical care and long-term care needs will increase rapidly. Actually, the national long-term care insurance may eventually have to pause or cut the services. We might then have to buy private services.

I’m not an expert in macroeconomics, but the imminent shortage of financial resources for both the pension system and health and long-term care is a growing issue for the society.

Mohsen Mostafavi: But it sounds like, in Japan, the situation is so much better than many other parts of the world in terms of the support that is coming from the government.

Hiroko Akiyama: Yes, so far.

Mohsen Mostafavi: Before closing, can you tell us a little about how you organized the team for a new kind of research institution?

Hiroko Akiyama: Well, the importance of interdisciplinary research has been talked about only for the past 30 or 40 years. And easier said than done. Many universities have set up funds to conduct interdisciplinary research, but there’s almost no success. Yet I’m optimistic about the positive achievement of gerontology.

I was asked to set up the institute 15 years ago. My background is in psychology, and I myself am interested in the aging society from the individual perspective. So I looked around at what the professors and researchers at the University of Tokyo who were enlisted at the institute were doing and found that some of them, about 30 people, were doing research related to aging. Then we had a two-hour meeting with everyone. The economists talked about their issue, people from the medical school about their issue, and I thought it was just like silos. They were not listening to other people. So I said, “We have a common field so let’s address and solve issues together!”

In fact, to set up a real network and coordinate was very difficult. Soon after starting the institute, we realized that we psychologists, for example, cannot solve an issue by ourselves; we need to work with engineers or experts from other disciplines on a common site. You have to collaborate—and not only among different disciplines but also with the city and industries as we’re actually doing now. It’s also important to produce a solution as some kind of “product” as a team.

Mohsen Mostafavi: That’s so great. We collaborate with a number of different institutions and professionals for our research, but I imagine the action of taking part can be quite challenging.

Professor Akiyama, this has been an incredible pleasure. Thank you so much for giving us your time today.

The total fertility rate for the year 2021, when the interview was conducted. The 2023 rate decreased to 1.26.

A super-aging society is a society with an aging population rate exceeding 21 percent.

The aging population rate for the year 2020.

A medium-sized, typical bedroom city in Tokyo suburbs.