Alone Again, Or: Two projects exploring life in Tokyo’s evolving fabric

Mohsen Mostafavi: We are involved in an exciting research project that’s looking at the future of urbanization in Japan. Partly what we are interested in is what was happening during the same period outside of Japan, in terms of people who are doing really innovative and exciting projects. And your Habitat project falls in that category. That’s why I wanted to ask you a little bit about the origins of your Habitat project, how you started. I know this was something that came out of your thesis at McGill.

Moshe Safdie: It began with a traveling fellowship that was granted to one Canadian student of architecture in each school in Canada. We traveled across the entire United States and Canada and visited both public housing projects and suburban developments. A real cross section. What impressed me was the inhumanity of public housing and most forms of high-rise housing regardless of income. At the same time, I saw the powerful force that propelled the population who could afford it to suburban single-family houses. I came back with this notion that people prefer to live in houses. And if we could give them the quality of life that you get in a house within an apartment building, then this might be a game changer. The idea was for everyone a garden, houses in stacked houses to form apartment buildings, rethinking the apartment building.

My thesis was entitled “A Case for City Living.” Just as I was doing this, Sandy van Ginkel arrived from Holland and gave a public lecture at McGill. He had been the partner of Aldo van Eyck. I was very taken with the ideas of Team X that he exposed me to.

I asked Sandy to be my thesis tutor, which was approved. I worked with him through the sixth year on the development of the thesis. And in the end I developed three housing systems. One of them was a superframe with prefabricated modules inserted and spiral formation forming gardens on the roofs of the units below them. The second was the load-bearing box system, prefabricated boxes which went up to 12 floors and were load bearing. And the third was a wall system, which was a series of walls that changed direction and set back and was maybe less interesting than the other two.

Moshe Safdie, Thesis 1960 and University Projects

Later, van Ginkel showed up in Philadelphia and announced that the World’s Exposition 1967, which became known as Expo 67, was coming to Canada. It was going to be in Montreal, and he had been put in charge of the master plan and was putting a team together. He wanted me to come back and work on the master plan with him. And in my young enthusiasm, I had the chutzpah, if I can use the word, to say, “Okay, I’d love to do that. But I’d like to have permission to develop my thesis as a potential exhibition pavilion in the World’s Fair.” And that was agreed to.

As a student, I was very into Le Corbusier, but Unité d’Habitation felt to me like a betrayal. There was, at the end, just a block building, the internalized streets in the air. These really dark corridors didn’t make sense to me. The building floating on pilotis had very little connectivity to the city. And there comes Sandy talking about the casbah organisée—I remember the term, it’s an Aldo van Eyck term—showing photographs of Dogon villages, Italian hill towns and projects that Giancarlo De Carlo was doing in Italy. And it just connected for me. I could see another path: a path that was a counterpoint to modernist orthodoxy.

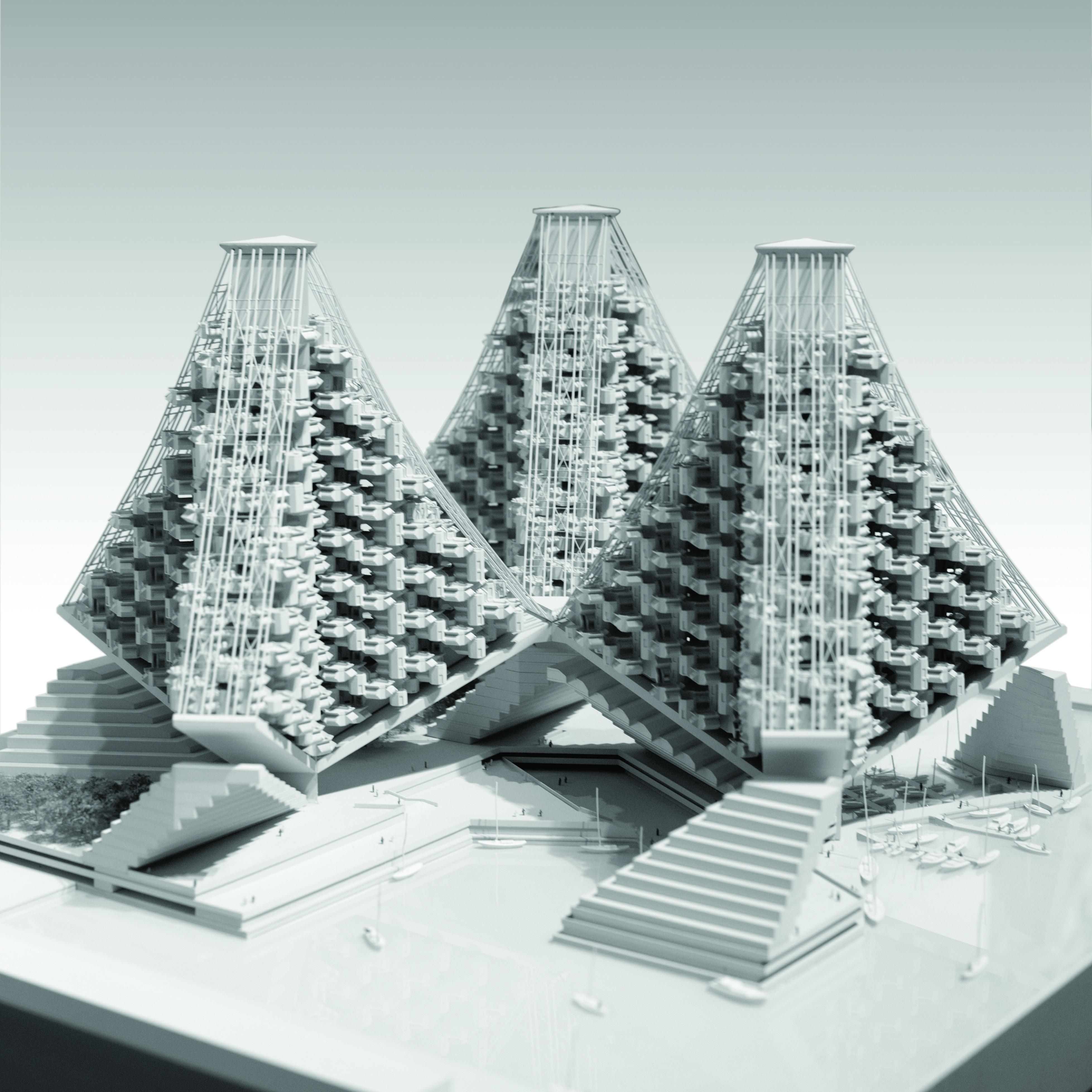

There was a master plan for developing Habitat. And the original proposal was for 1200 units covering the entire peninsula, going 25 stories high and including a hotel, school and some office space and shopping. It was a community.

Montreal Expo 67. Master plan

With that plan and the model (a big model of the original scheme, which still exists), we traveled to Ottawa to present it to the cabinet. But they decided that they could not support the tax relief program that was proposed to realize the entire program and simply gave us a budget of $15 million. With those terms, they suggested, “Build what you can.”

At first, I thought, “This is…I’m not going to do that.” I considered walking away. The dilemma was that the factory itself would cost $5 million. But then I figured out I could build a small section, about a fifth of the original, and also it was going to be located at the end of the site, which was much more constrained in its width. We ended up building a twelve-story section. I would say that if the original design was aspiring to be a section of a city, the project we built was more of a village.

The original scheme was trying to suggest where we go if we can organize mixed uses three-dimensionally in a way that goes beyond the extruded individual building, each on its own parcel. It also started creating a hierarchy of component parts of the city—the hillsides, where people live, and valleys below, where communal activity of the public realm occurs. None of that could have been demonstrated in the project that’s built.

Moshe Safdie, Habitat 67 in Montreal Expo 67. Original proposal, 1963. Sketch

Moshe Safdie, Habitat 67. Original proposal

Moshe Safdie, Habitat 67. Original proposal

Moshe Safdie, Habitat 67. Original proposal. Exterior view showing module connections

But the built project still had its power. It made people realize that in a multistory building, which could extend even beyond 12 floors, you could have the quality of life they associate with a house. There is no question, in terms of the public response, that this really resonated with people.

Mohsen Mostafavi: How would you describe, if there are one or two main differences for you, between what you were trying to do and what you think the Metabolists were trying to do? What do you think are those differences?

Moshe Safdie: I was approaching it more from the individual building block. I started with a house, and everything I was doing was taking the house, assembled, accumulated, aggregated, with a question of—how does that fit into the city as a whole? As I went forward, I became more and more concerned and interested in the mixed-use and how things work together. In the New York project there’s a whole lower level of other facilities below the housing. I would say that the Metabolist work started from the consideration of the whole complex. They were all about the totality. I think there was less focus and concern with the quality of life, of an individual family or the individual person within the complex. The texture was very different. There was less emphasis on the identity and balance of community and privacy which were the underpinning of Habitat.

Moshe Safdie, Habitat New York II, 1967–1968

Mohsen Mostafavi: What do you think now reflecting on the Metabolists and reflecting on the first version of Habitat? You’ve gone on to do other projects that are inspired by this. I’d like to know what your own reflections are about the original Habitat—the pros and cons, what didn’t work. What did you try to address? Is this sort of a visionary dimension that Habitat had for you? Do you feel you still want that in other projects that you’re developing in China or other places?

Moshe Safdie: When I go there now, it’s as if somebody else designed it. You have distance, and your first question is, how the hell did anybody get away with this? How could “they” ever realize that? When I go there now and I see the complexity of the detailing, and the technology that went into it, and I think of a bunch of kids who never built a building before, because my office was all made up of people of my generation. It’s very hard to comprehend the sophistication versus the lack of experience.

I think at the level of the environment, the living environment, it is extraordinary. I look back 50 years, extraordinary. You go there, if you built it today, it would be as fresh and relevant, and still utopian in many ways, if you realized it today.

Moshe Safdie, Habitat 67, Montreal. Current view

Mohsen Mostafavi: Many of the projects linked to the Habitat model, they really are about large-scale projects that construct a community by themselves. Because you’re on an island, or you’re inside, the idea is that you don’t build housing only but something that could have an infrastructure to support it. Today, more and more people are also interested in what could happen to the future of cities beyond just housing. I wonder how you see the current of large-scale development practice.

Cité des Îles, Montreal, 1968. A proposal for post-expo expansions of the islands to form a linking city in the river

Moshe Safdie: I would say, in the big picture, there is a new typology that’s very troubling but very commonplace. It’s mostly in Asia, but I see it in many other places. Developers get a large-enough parcel where they would do a multilevel mall as a podium and three or four or five towers above. Generally, they will do office and housing and hotel towers, and a million or more square feet of shops, and lots of parking. The general approach is extremely introverted. It’s a typology that actually demands a response—because it’s introverted, it does not connect to the city’s street system. In itself, it becomes a collection of towers that are independently conceived with little concern for how, collectively, they form a city.

The other issue is that there are certain limits to what you can do with towers, each on its own parcel in terms of light and exposure and connectivity. Whether it’s Habitat-like or not, bridging between towers to achieve certain spaces up there, connectivity that’s meaningful in terms of the programs of the building, and even connectivity from project A to project B beyond the street level. What are the possibilities of incorporating parks and landscape spaces at various levels of the city to increase the amount of green and park space in cities? The connectivity potential and the public realm. I don’t think we’ve cracked that yet.

And what’s the next evolution in transportation? It’s coming, but we don’t know what it is. There’s a whole batch of things there that I think involve the big picture but also the small picture.

Mohsen Mostafavi: I learned that you have to be patient, and you have to try different things. It’s really amazing what you said about going to visit Habitat now, 50 years after the fact, and being able to see it distant from yourself, seeing yourself as somebody else, who was the person who did this? You know, it’s a sort of privilege in some ways.

All images courtesy of Moshe Safdie Architects unless otherwise specified.