Alone Again, Or: Two projects exploring life in Tokyo’s evolving fabric

Mohsen Mostafavi: I’m so happy that you can take the time to speak with us about your work on urban dramaturgy, the role of entertainment, expositions, and urban politics. You have spent a lot of time working on urban issues and especially the development of Tokyo. Can you tell us a little bit about how you became interested in Tokyo? What were some of the first things that excited you about that investigation?

Shunya Yoshimi: I entered the University of Tokyo in 1976. The mid-1970s were a turning point, moving from a time of political activism toward cultural activities and performances. In my case, I joined a theatrical performance group. I was crazy about the theater in the 1970s.

From my perspective, the city and urban activity seemed to be a kind of theatrical performance with a scenario, a stage set, actors, and so on. My question was, how are these cultural performances organized? What is their structure? In order to understand that, I became very interested in the relationship between spatial formation and people’s behavior.

In my undergraduate days, I took a class taught by Professor Hiroshi Hara, a very famous architect in Japan. I was a student of sociology and the humanities, but nevertheless he invited me to join his lab for one year. There, I met Kengo Kuma, Riken Yamamoto, and many other exciting young architects. Although I had no knowledge and no ability and no training in architecture, we had many interesting conversations. After one year, I came back and wrote my sociology thesis, which became my first book, Dramaturgy of the City.1

In that book, I tried to analyze the structure of the gathering in the city, and this was my starting point to understand and get involved in a study of the city of Tokyo.

Mohsen Mostafavi: This is a fantastic story. Could you say a few words about that book in terms of what kind of material you were actually reading?

Shunya Yoshimi: I wrote the book in the mid-1980s, and in those days I was mostly interested in the relationship between those kinds of performances and power. Of course, Tokyo has been the center of political power and economical power, but in those days I was more interested in power as it was understood by Michel Foucault. My hot concept in those days was the gaze and visualizing.

Shunya Yoshimi: In these urban spaces, I think a new gaze—a new system of visualization—was implemented in the late nineteenth century. This new perspective was introduced in many different ways in Tokyo. For example, in the Ginza Red Brick District, constructed in 1872, you can see how the Japanese people gazed, watching Western civilization from the middle of Tokyo. You can see the western seas, the locomotive, and the civilization from this district.

Utagawa Kuniteru II, Realistic Illustration of the Main Street of Brick Masonry in Ginza, Tokyo, 1873 (early Meiji period). Source: Tokyo Metropolitan Library

The Tokyo Station building, designed by Kingo Tatsuno and constructed in 1914, had only a western entrance with vista, and no eastern entrance. That is because the Imperial Palace lies on the west side of the station. So all the passengers who got on or off at the station were encouraged or forced to see the Imperial Palace. Gazing was structurally and spatially organized between the passengers and the emperor.

Tokyo Station, 1914, photographed before World War II. Image courtesy of Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library

These kinds of gazing still exist in a big city like Tokyo. If we look at the Shibuya Scramble Crossing, which has become a famous space today, its most important dimension is that people around here are always gazed on from the global perspective, from around the world.

Shibuya Scramble Crossing, Tokyo. Photo: ©Luciano Mortula/123RF.COM

In my first book, I analyzed many of the people’s gathering places, or sakariba, in Japanese. Sakariba is something like Times Square in New York, and in Tokyo it is Ginza, Asakusa, Shinjuku, and Shibuya. I researched how these gathering places moved from one location to another over time. What kind of dramaturgy was created in the spatial changes and why?

In all of these urban spaces I looked at the gaze and the power formation, but I also realized there was something more. In my research I was really trying to understand what this “something more” was. It wasn’t only the power structure or gaze but also a kind of sentiment or a much more dramaturgical, much more…I would say some kind of interruption and movement and excitement. I sensed that the historical moment of the city emerged beyond these gazing power structures.

Mohsen Mostafavi: This is interesting, both in terms of you using the concept of the gaze to study power structures and institutions of power, and also because you yourself are looking at a lot of visual materials as a way of understanding the history of the city. We are very inspired by your work and interested in studying the city not only in terms of its history but also in terms of its future.

It’s a kind of cliché—but many people who look at Japanese organization say they don’t understand the way the city works. They find it very chaotic and confusing. Part of your research has been to try to explain the logics of the city and the organization of the city. But what are your thoughts in terms of the evolution of a city like Tokyo? What are some of the key characteristics of Tokyo in terms of its emergence?

Shunya Yoshimi: Indeed, through visual materials I believe we can understand the evolution of Tokyo or, in another sense, people’s imagination about the evolution of Tokyo. And I think the most important concept, in this sense, might be destruction.

Postwar Japan, especially postwar Tokyo, was extremely entangled with the imagination on destruction. Maybe the most globally famous example comes from Godzilla produced in 1966. Tokyo was destroyed by the big monster, and this image was so popular. And that was only the start of the destruction.

The symbolic monument, or monumental building, from the 1950s to the 1980s in Tokyo might be the Tokyo Tower, constructed in 1958. And Tokyo Tower was destroyed almost every year in the social imagination by so many different monsters: Gamera, Mothra, King Ghidorah…all of them destroyed Tokyo Tower.

Tokyo Tower—brochure from the late 1950s

And not only Tokyo Tower. The city of Tokyo itself was destroyed in many of the images in manga and anime. In Akira (1984) by Katsuhiro Otomo, Tokyo was devastated by a superpower. In the animation Neon Genesis Evangelion (first published as a manga from 1994 to 2013) and the movie Shin Godzilla (2016), Tokyo was wrecked again.

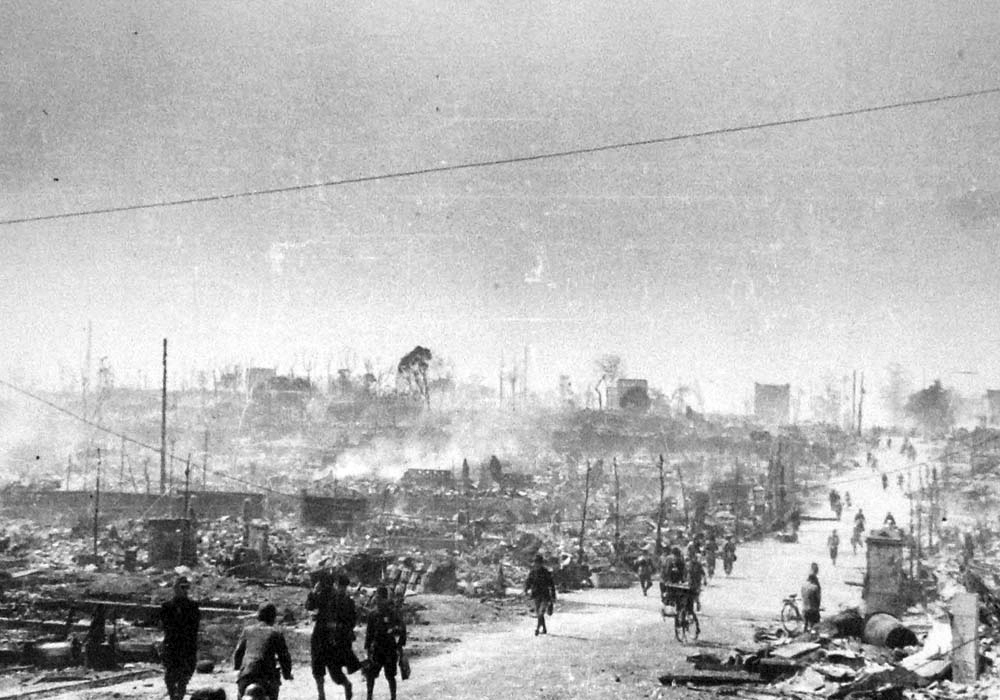

All this destruction started from one very, very strong image from 1945—the American bombing. Tokyo was burned and nothing remained. Tokyo started from that kind of destruction. But at the same time, Tokyo became an American city, a city of Americanism, over the next 50, 60 years. So this ambiguity and these two dimensions of the city are very important when we think about Tokyo since the late twentieth century.

Mohsen Mostafavi: This is fascinating. Are you saying that the destruction of 1945 stayed resonant with the people of Tokyo in the 1950s and beyond, in the form of all these images that you showed of Tokyo Tower? Is there some kind of trauma still present in the 1950s in the minds of people who are living in the city that is already developing?

As you said, there is a kind of Americanization—the Americans were still there until the Olympics. And they were, in a way, part and parcel of the development. At the same time, if Tokyo Tower was being destroyed, it means that people were also still traumatized by the war. How did people reconcile these two conflictual conditions?

Shunya Yoshimi: In general, most ordinary people in Japan have already forgotten what happened in 1945. For most young people, the destruction in 1945 is almost nothing. I think people still kept the memory in the 1950s and early 1960s, but after the rapid economic growth, most of them came to be focused on affluence and consumerism. You talked about a reconciliation. Most Japanese people have already been almost completely Americanized. So that conflict is not an issue for most people.

But with the cultural imagination, it was different. In the 1950s and 1960s, the devastation still remained. Then, in the 1970s and into the 1980s, it settled deeper in the cultural imagination, especially in Japanese manga and animated films. Katsuhiro Otomo, Hiroaki Anno, and some other Japanese animators were so creative because their kind of imagination came from the deep sense of destruction.

And if I may elaborate on the issue of destruction, I should also point out a very important aspect of the history of Tokyo, which is that the city was occupied three times: first by the Tokugawa shogunate in the late sixteenth century, then by the Satsuma and Choshu corps of the imperial army from Kyoto in the nineteenth century, and lastly by America. Many historical and memorial traces of these occupations remain today: we can see traces from the days of Edo, of ancient Tokyo, and of the Meiji. All different types of the historic power, space, or time still exist thanks to the very complex topography of Tokyo. That is a very exciting thing.

So when you talk about reconciliation, one possibility might be to consider, how we can deal with these different times, spatialized times in this city? This reconciliation should be strongly connected with urban design in the city.

Mohsen Mostafavi: So you’re saying that the city of Tokyo is a kind of palimpsest that shows the traces of its past, of its history. And every time that the city is destroyed, which is three times now, it reconstructs itself in relation to this palimpsest, in relation to what was there before. The historical trace is one regulating principle, one guideline for the evolution of the city building itself on its past, being destroyed.

But just staying with that idea, you also touched on the question of memory and the role of people thinking about the city and remembering things about the city. Tokyo Tower is not a very old structure, historically, even though it is a monument. Were there specific monuments in this city, any important structures that were destroyed—for example, in 1945? What is the relationship between monuments and memory in the Japanese context?

Shunya Yoshimi: The most interesting example would be Ueno Park. After the first occupation by Ieyasu Tokugawa and the Tokugawa shogunate, Edo Castle was built in the middle of Tokyo. But they constructed another religious city in the Ueno area with Kan’ei-ji Temple. It was huge and became the most powerful and imposing presence in the area. During the war for the second occupation, Ueno was burned by the new army, and the area was then rebuilt with many museums, an exposition site, a zoo, a concert hall, and an art university, as well as the University of Tokyo—the institutes of modernity. After the Tokugawas, Ueno changed from a religious city to a city of modernity. Still, if you visit Ueno Park today, some of the most exciting buildings are not museums but old temples, especially Toshogu, and small ancient shrines that existed even before the Tokugawa shogunate.

Most visitors to Ueno come only to see the pandas and the modern museum. But if we open and restore some of the historical sites in this modern park, we can show that modernity is not one-dimensional but has many different layers. Reconciliation or a dialogue between the different historical times should occur or should be activated spatially for visitors to Ueno Park. Ueno is a typical case, but similar things exist in many different places in Tokyo.

Mohsen Mostafavi: We’ll come back to Ueno because I know it’s very close to your heart. But for now, let’s focus a little bit on the future. If Tokyo has been a city of destruction—you mentioned three occupations and cycles of destruction—what does this mean for the future of this city? How do you see the future of Tokyo, and what are the themes and topics that require the most specific attention?

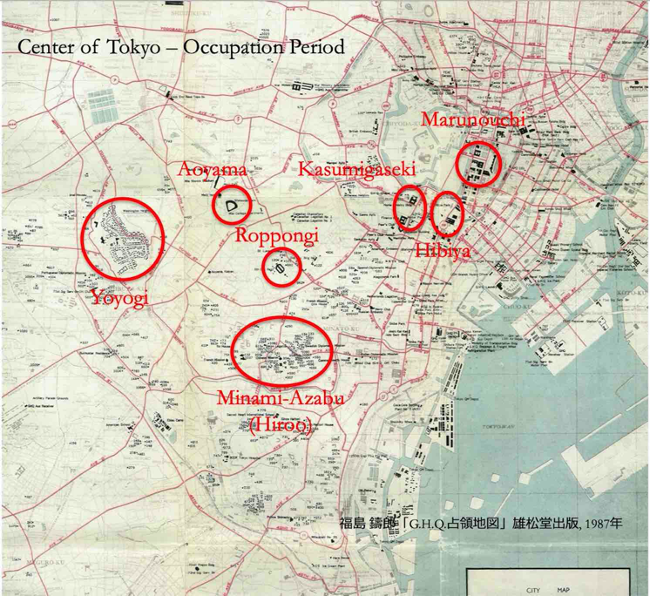

Shunya Yoshimi: In order to answer your question, I need to mention the Tokyo Olympic Games, especially in 1964, because that was when Tokyo changed direction. During the third occupation, many of the American military facilities were concentrated in the south and the west of the city. The reason for this was very simple—the American military forces took over sites used by the Japanese military. Yoyogi, Azabu, Roppongi, Aoyama, and Hibiya—all were central for the Japanese military before the war.

The central part of Tokyo during the US occupation, 1945-1952. From Juuro Fukushima, GHQ Tokyo senryo chizu [GHQ occupation map of Tokyo] (Tokyo: Yushodo Shuppan, 1987)

This kind of change is not really change—it’s some kind of continuity. Some of these American military facilities were then replaced with Olympic facilities. The most famous and most important place is Yoyogi, which had been an American military base called Washington Heights, and it was returned to Japan just before the Tokyo Olympic Games.

Tokyo after American air raids, photographed by Ishikawa Koyo in March 1945

Washington Heights, Yoyogi, photographed in 1954. Source: The Mainichi Graphic, January 13, 1954

Kenzo Tange, Yoyogi First Gymnasium, built after Washington Heights. Photo/Map: Arne Müseler / CC-BY-SA-3.0

If you look at the photo taken in Washington Heights in Yoyogi, you can see the American houses of the American army and also the houses for Japanese people. You can see the big difference between them. Of course, for ordinary Japanese people, American houses were glorious and rich and affluent and fantastic. And it was very reasonable that all the Japanese people wanted to be American.

Washington Heights, Yoyogi, photographed from the neighborhood in 1960. Photo courtesy of Shibuya City Office, Public Relations and Communication Division

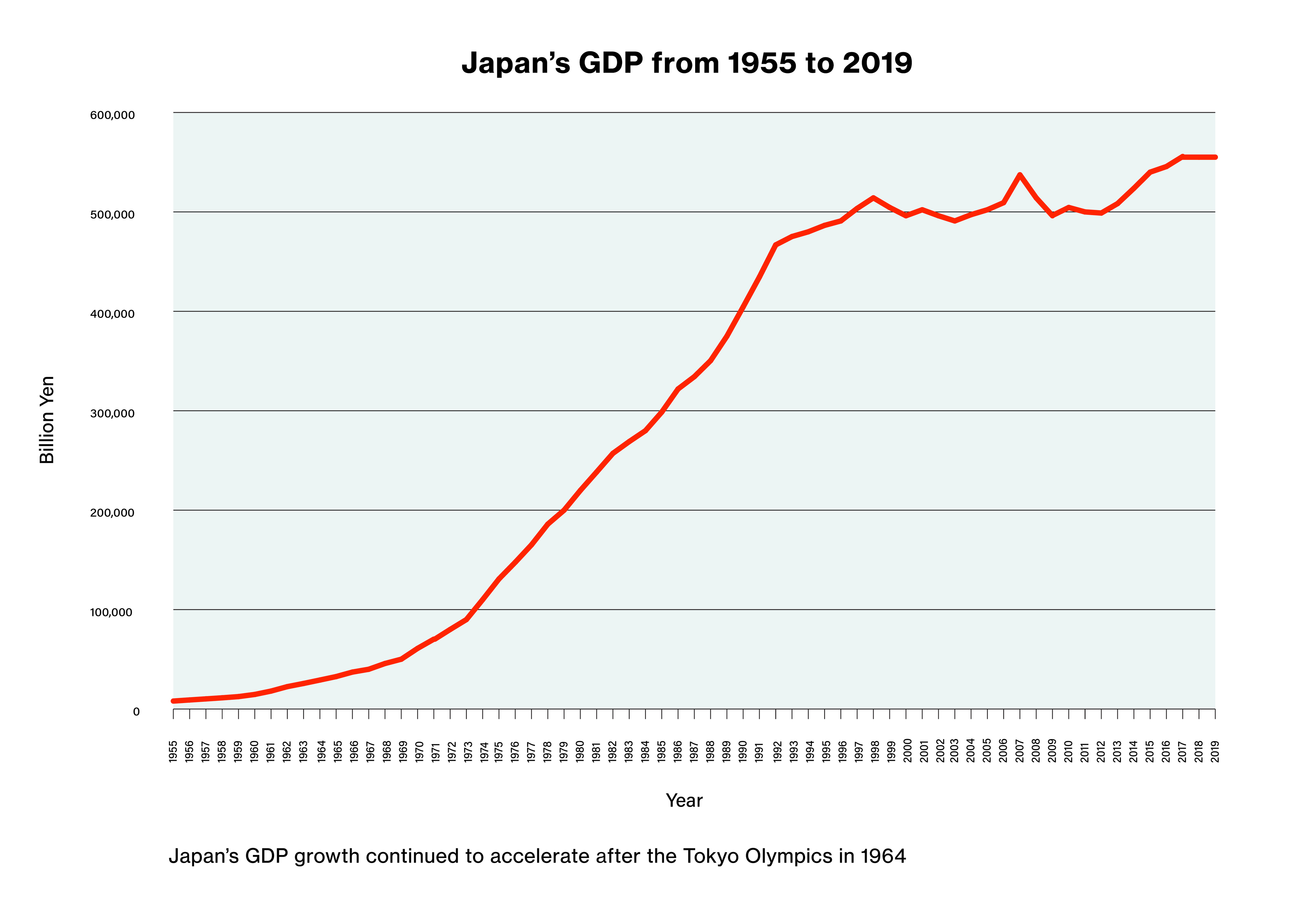

After 1964, the American military city in Tokyo changed to the Olympic city. And for the 1964 Olympics Games, the city of Tokyo pursued faster, higher, and stronger development. “Faster, higher, stronger” is itself a slogan of the Olympics Games. But the Japanese people continued to pursue this direction enthusiastically after the 1960s. And in this process, we lost rivers, canals, tram lines, old districts, a slow pace of life, and war memories—all of this.

At the same time, the cultural center of Tokyo shifted. Until the 1950s, it had been in Ueno, Asakusa, Ginza, and Nihonbashi—basically, in the northeast. But after the 1960s, the most popular, fashionable areas became Roppongi, Akasaka, Aoyama, Harajuku, Shibuya—areas concentrated in the southwest.

Shunya Yoshimi: I think what we can try to do is change that direction. Faster, higher, and stronger is the slogan of the developer. But we are living in the age of after-development. For us, sustainability, resilience, diversity, and recycling—these things are more important for the future city.

What we are trying to do, symbolically, is to move the cultural center of this city from the southwest back to the northeast. What’s interesting is that a prototype for this idea already exists. Just after World War II, in the late 1940s, people in and around the University of Tokyo tried to construct a kind of cultural city in the areas of Ueno, Hongo, and Koishikawa. The drawings were made by Kenzo Tange.

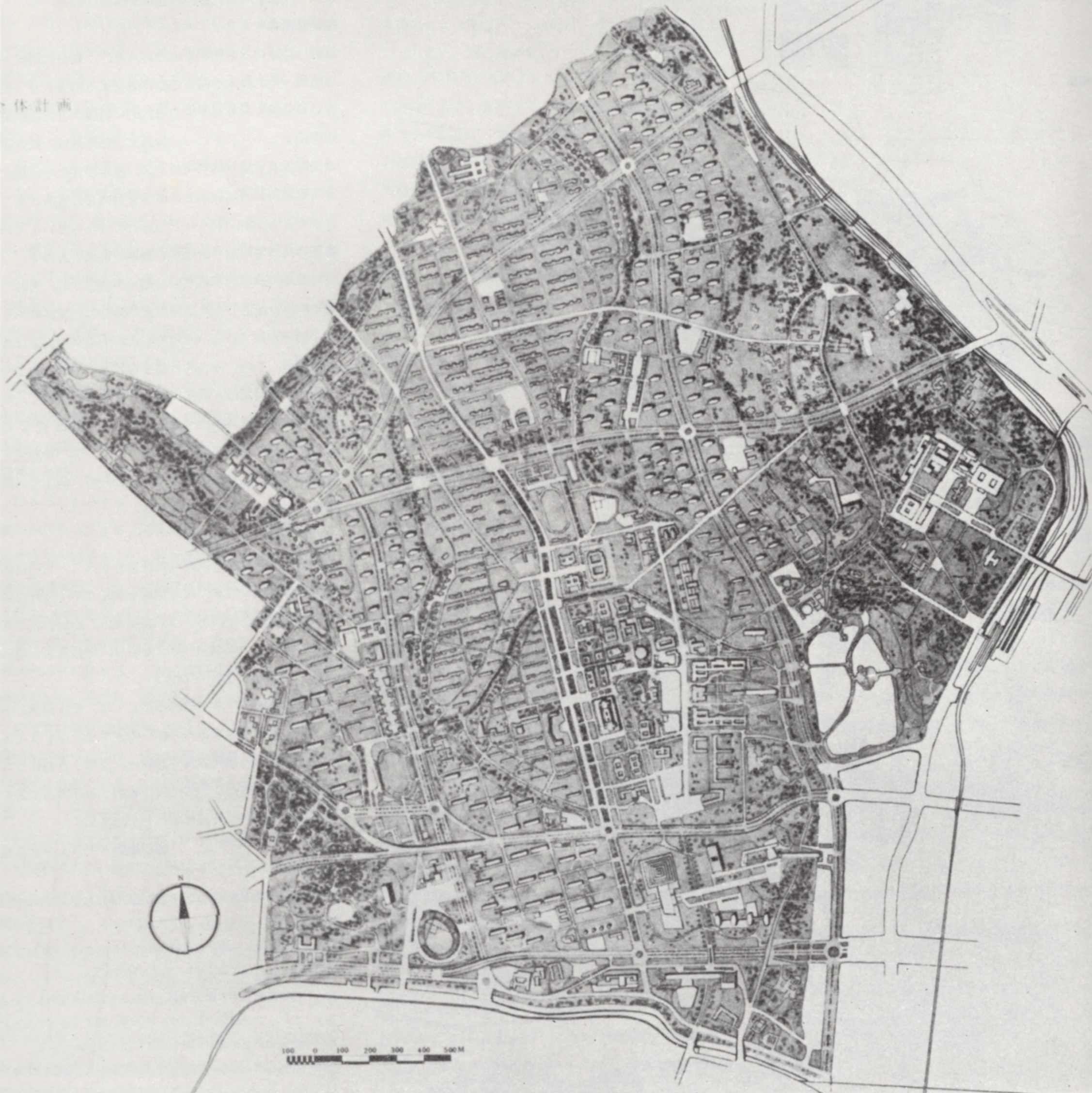

Kenzo Tange, Sachio Otani, et al., Hongo Plan. A master plan for a “university city” in the northeast part of central Tokyo. Source: "History of Urban Planning in Modern Japan," Toshi Jutaku, April 1976

It was to be a “university city,” like Oxford, but in Tokyo. Hongo is where the University of Tokyo is, and Ueno was a center for art. Koishikawa, in the lower left, was the area for recreation and Yushima, in the south, was an area for international exchange. The team made a plan, but it was not realized.

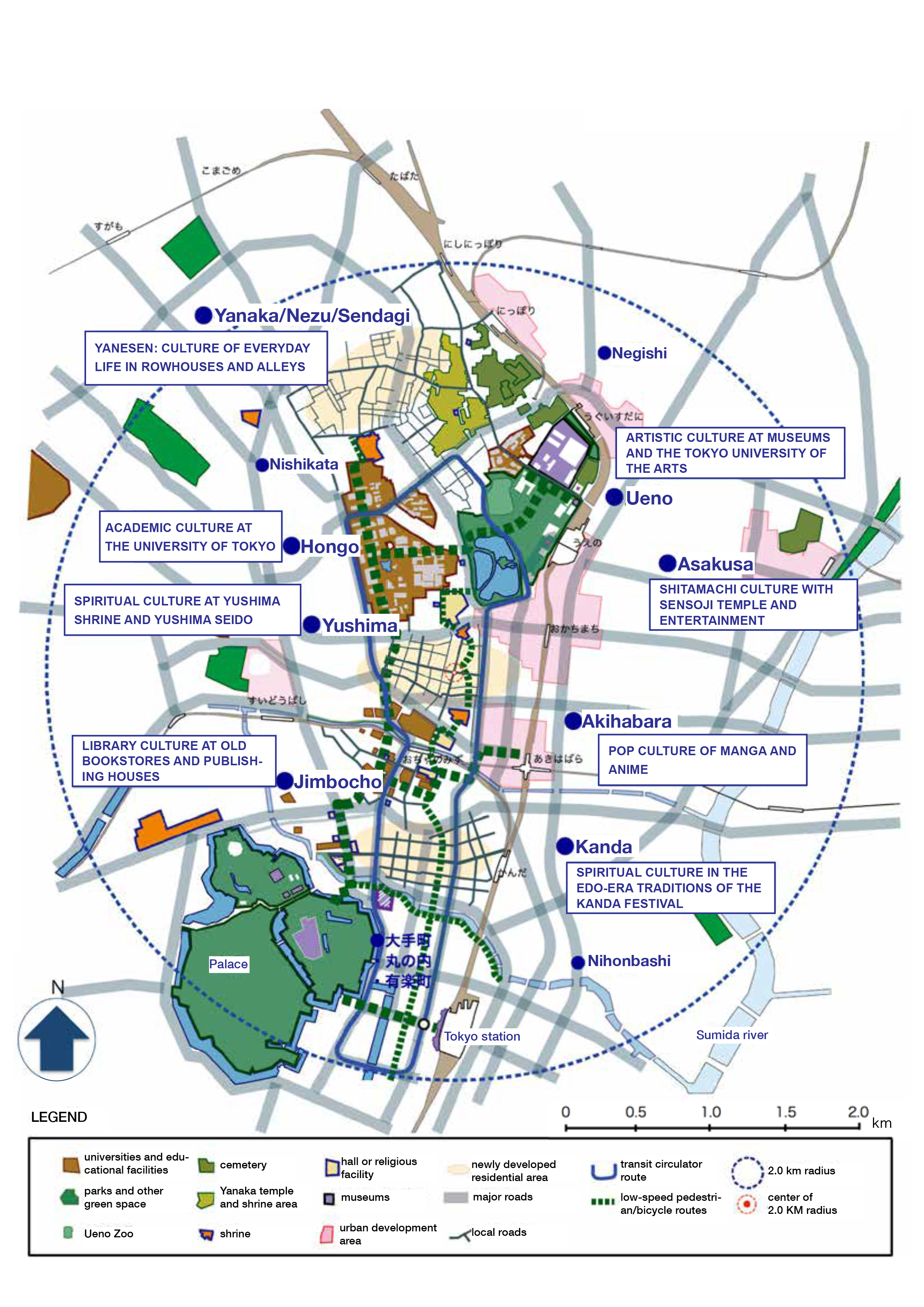

I think we should revitalize the historical heritage in this city. So much of that heritage from the Edo era or the Meiji era is concentrated in the northeast, which also has the potential to be a hub of university knowledge and art and culture.

In this northeast area, there are also many temples and shrines—not only the Shinto shrine and Buddhist temple but also a Catholic church, a Protestant church, a Confucian temple, a Russian Orthodox church, and an Islamic mosque. Why don’t we try to connect all of these different religions? The religious diversity in Tokyo is actually amazing.

The other thing we are now trying to do is reconstruct slow mobility in this city. A tram system existed in Tokyo until the early 1960s, and it was one of the major public transportation systems. But by 1964, with the Tokyo Olympic Games approaching, the tram ride was almost abolished because it was too slow. Tokyo needed to be fast—

Mohsen Mostafavi: Faster and stronger.

Shunya Yoshimi: Yes, faster and faster and faster. But we need to reevaluate slow mobility in the twenty-first century. Why not reconstruct the tram ride in Tokyo? This future tram would shift from faster and stronger toward a better quality. Resilience and cultural sustainability are among the most important concepts for a future city. The vision for Tokyo in the twenty-first century should be completely different from the one in the 1960s.

Tokyo Cultural Heritage Alliance, Vision for the Tokyo Cultural Resources District, 2020. Enhancing the already-existing cultural resources in central Tokyo's northeastern neighborhoods is the theme of the alternative urban development plan advocated by this alliance, whose diverse members, like Prof. Yoshimi, come from academia, cultural institutions, and industry. Image courtesy of the Tokyo Cultural Heritage Alliance

Mohsen Mostafavi: Well, this idea of the cultural district of the city seems very exciting. Is this project something that’s actually supported by the universities? Who is behind this plan with you? And how will you try to implement this vision?

Shunya Yoshimi: It is challenging. There is bureaucracy and conservatism in many museums in Ueno and also in the government—a reluctance to change. But there are many students and professors who understand the importance of change and also many people in the big companies and in the government.

In the late nineteenth century, at the end of the Tokugawa shogunate, there was a very interesting word in Japanese: Dappan-shishi. It refers to a samurai who purposely left his han (or pan) feudal clan, which was the established social organization unit. Many samurai understood that Japan was in crisis facing Western expansionism and needed to change. So they sometimes went outside the established institutions and connected with each other beyond the borders of those institutions. In the end, they changed society in the 1860s.

Similarly, the first thing we can do is collaborate with one another—the university professors, the museum curators, and so on—working toward the same end, beyond institutional borders. Maybe the University of Tokyo or the Japanese government cannot support our plans officially, but they can offer some other form of support. Maybe not all the big companies can support us, but some can.

The politics are very complicated. My project has no guarantee of success—it is very big and very challenging.

Mohsen Mostafavi: I think that one needs to have these kinds of visions to inspire people and to show what is possible. And I suppose, inherent in your emphasis on the idea of Tokyo as a cultural city, there is the necessity of creating a cultural hub to counteract, let’s say, what has happened in Roppongi or other areas with big developments that are made possible by new liberal policies.

I think this issue of how one makes these projects possible politically is very important. We are studying some of the large-scale developments that are happening in Roppongi and Nihonbashi. I think even the big developers now are seeking a way to work more with communities and to work with small neighborhoods. So it would be interesting to think what other types of development could occur: that is, not only large-scale developments but different-scale types of development. I think your project fits into this idea of alternative visions to complement some of the things that are happening today.

Shunya Yoshimi: Exactly. In the southwest area—Roppongi and Toranomon, Harajaku and especially Shibuya—each landowner has a relatively big space, and large developments are possible with big corporations, big capital. But in the northeast, each land parcel is relatively small. So it is quite difficult to do a large-scale development. This is not good news for the big developers, but I think it is good news for the grassroots movement for a new urban design. In order to change this district, we need to connect small things together.

Tokyo does not have a British Museum or a Louvre. Tokyo does not have the Smithsonian. But Tokyo has so many small, good places—restaurants and institutions and small museums and shrines and temples. The most important innovation for this city might not be a huge museum or a huge institution or a huge building. Rather, the key might be to connect the small, good places or things in a new network. That would be a fantastic future for this city.

Mohsen Mostafavi: I want to ask you one final question, which is about the Olympics. You already touched on the 1964 Olympics, and you’ve spoken before about the importance of the planning for the 1940 Olympics and its influence on 1964. Next year we will have the Olympics that was supposed to happen this year, with the stadium designed by Kuma-san and built by Taisei. You’ve just finished a book on the Olympics,2 and so I wonder what you think about next year’s Olympics. How do you fit next year’s Olympics into this cycle of preparations for 1940, 1964, and then the 2021 Olympics?

Shunya Yoshimi: Do you know Naomi Klein’s bestselling book, The Shock Doctrine? She said that after a huge shock like 9/11, or maybe COVID-19, new and controversial policies can be introduced while people are distracted by the crisis. I think in Japanese society we have, not a shock doctrine, but a kind of festival doctrine or Olympic doctrine. Japanese society is not easy to change, as I explained. Yet, from the perspective of the government or the ruling party, change came to this society through festivals and big events.

The 1940 Tokyo Olympic Games were planned because of the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake, which destroyed Tokyo. Massive reconstruction went on through the late 1920s, and at the end of this process, the government thought we needed a celebration. Why not have the 1940 Olympic Games in Tokyo? But we couldn’t because war broke out. So not only could we not have the Olympic Games but also we had the city completely destroyed again.

After 1945, after the total destruction, Japanese society in Tokyo was reconstructed and revived throughout the 1950s. And the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games were a celebration of the recovery from 1945…. Originally, the second Tokyo Olympic Games were planned to show the recovery from the Japanese economic depression of the 1990s, but after the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, it was decided that the next Tokyo Olympic Games should celebrate the recovery from the earthquake and the destruction.

If we can really host the Olympic Games in 2021, there is one thing we need to think about. Historically, after the success of the Tokyo Olympic Games in 1964, many people forgot what happened in 1945. They lost the historical memory before 1960. I do not want to forget what happened in 2011, including the Fukushima nuclear accident. We need to remember 2011, what happened in this country…. The Tokyo Olympic Games in 2021 should be the moment for remembering that history, remembering the historical past. If we can do that, it will be a big change from the previous Tokyo Olympic Games. This is my hope for the Tokyo Olympics in the future. It should be completely different from the past.

Mohsen Mostafavi: It’s such a big challenge for the Olympics to be not only a source of the rebuilding or the construction of the future, but also the reconstruction of some form of togetherness or the reconstruction of some form of collective memory, which is very, very key.

I think one of the exciting ways for that to happen today is for more and more people to focus not only on Tokyo, but also on other cities and the relationship, as you mentioned, with regions like Tohoku or Kobe. People from those regions should also feel that they are part of this discussion.

One of the things that we have noticed during some of our investigations is a sense of powerlessness among some of the young people, who are moving to the Tokyo suburbs or even to the countryside, trying to work in the context of circumstances where their voices can be heard and where they can really participate in the politics of everyday life. How that politics of engagement can also be more valid, more implemented, in Tokyo will be surely one of the ways to realize your dream of having the 2021 Olympics, which will hopefully happen, be different from the ones in the past.

I really want to thank you for this fascinating exploration of Tokyo.