Portraits of Landscapes—Part 1

Mohsen Mostafavi: Welcome, Inui-san. It’s wonderful that you could join us today.

Kumiko Inui: Good evening.

Mohsen Mostafavi: I’d like to begin by asking you about the relationship between your practice and the larger question of urbanization in Japan. What is your reaction to the way development occurs in Japanese cities today, with so many very large-scale projects under consideration? What is the role of smaller practices like yours in such a context?

Kumiko Inui: In the big cities, market logic has come to dictate most projects. The government controls these market-based projects, encouraging large-scale development through deregulation.

It looks like the construction industry is competing globally between cities. But in reality, the government is using urban development as a tool for economic growth. It seems to me that people are losing autonomy in their urban activities due to those huge developments. With rents being so high, the only tenants are big corporations, and the commercial floors are occupied only by national chains and restaurants. So it’s not an environment that fosters unique stores and unique urban culture. And the projects that come out of these massive developments are not popular after completion because they are done independently of the local culture—it’s the developers who determine the future of the place, and they do not have roots in the community.

Yet I should note that development entities that must continue to do businesses in the area, such as private railroad companies like Tokyu or Odakyu, are a little different. They are interested in creating sustainable value. They have to keep the value along their line in order to maintain the train occupancy rate. So they may figure out a way to connect development with existing urban culture, and they may want small offices to do so.

Mohsen Mostafavi: Are you saying that, as developers, the railway companies have a different attitude than large-scale developers? Because of course, in many instances, railway companies also need to create profit. In your assessment, how are railway companies different from big developers?

Kumiko Inui: The railway companies have to keep doing business in the area after the completion of the development. They cannot escape from the land along the line, and that makes a difference. By contrast, most developers just leave the area once the project has reached completion.

Mohsen Mostafavi: I think many developers now are also interested in the continuity of their own projects because if their projects are not successful, their profits will go down. But I understand your main point about the relationship to infrastructure and the continuity of a neighborhood, and probably the railway companies are more invested in that.

Mohsen Mostafavi: Related to this question of the role of the railway companies, I know that you have been doing some very interesting work outside of Tokyo, in smaller places, like on Kyushu island, focusing more on infrastructure projects. Can you explain a little bit about how you became involved in these projects for the ferry company and for the railway company?

Kumiko Inui: There are two clients for the Kyushu project, the municipality and the national railway company, commonly called JR. They selected five young architects and asked us to submit our proposals. That was in 2011.

Mohsen Mostafavi: How is this kind of project on Kyushu different from one in Tokyo or Osaka?

Kumiko Inui: Nobeoka [Kyushu island] is a mid-sized city with a population of around 130,000. There is a large industrial presence in that city, but business had been in decline and the downtown area was deserted. As you might know, in Japan, the downtown area is almost always around the station. So the municipality and the JR thought that the station area was the best point to revitalize the city.

Kumiko Inui, Nobeoka Station Encross, 2018. Aerial view. Photo: Daici Ano

Mohsen Mostafavi: How does your station help revitalization?

Kumiko Inui: My project is not about the station itself. The site is beside it, and the building we designed includes spaces for civic activities like a library and a community center.

Kumiko Inui, Nobeoka Encross, 2018. Front view of the complex of public facilities integrated with the central station of Nobeoka. Photo: Daici Ano

Kumiko Inui, Nobeoka Encross. Library and lounge on the second level. Photo: Daici Ano

Kumiko Inui, Nobeoka Encross. Section view of the ground and upper levels. Photo: Daici Ano

Mohsen Mostafavi: And you did also the ferry terminal project. How did you become involved in that project?

Kumiko Inui: I joined the proposal for that ferry terminal.

Mohsen Mostafavi: Does this mean that there are opportunities for younger practices to work outside of big cities like Tokyo and Osaka? To work on smaller projects through competitions?

Kumiko Inui: I think so. In Tokyo, there are few competitions or proposals, but outside Tokyo and Osaka there are plenty of projects we can join. Of course, those projects are by the municipality.

Mohsen Mostafavi: And what’s important about the ferry terminal project?

Kumiko Inui: The ferry terminal is for tourism to Miyajima, where there is a very famous shrine. Most ferry terminals in Japan are just buildings, interiorized buildings. But since Miyajima has good weather, lots of sunshine and a calm sea, I tried to open up the building and make a lot of exterior space under the roof.

Kumiko Inui, Miyajimaguchi Passenger Terminal, 2020. Semi-external space. Photo: Daici Ano

Kumiko Inui, Miyajimaguchi Passenger Terminal. The complex is oriented toward Miyajima island, a World Heritage site. Photo: Daici Ano

Kumiko Inui, Miyajimaguchi Passenger Terminal. A network of public-use facilities with different functions

Kumiko Inui, Miyajimaguchi Passenger Terminal. View from the pier toward the Inland Sea. Photo: Daici Ano

Mohsen Mostafavi: Right, inside-outside.

Kumiko Inui: And I tried to combine the activity at the ferry terminal and the activity in the surrounding area.

Mohsen Mostafavi: Are there lessons that you have learned from these projects, lessons that could be applied to big cities?

Kumiko Inui: I think we can apply these lessons to Tokyo, but we cannot apply them to the big projects. I mean, Tokyo is big, but if you look closely, Tokyo is a combination of very small and local areas. So we can apply these lessons to local areas in Tokyo.

Mohsen Mostafavi: I know that when you were teaching at Tokyo University of the Arts, your research focused on this idea of small spaces in the city. What did you discover about small spaces? What can happen in small spaces in Tokyo?

Kumiko Inui: I worked with the students to identify suitable sites. And then we examined examples of activities and situations in which people operated autonomously and often in symbiosis with others.

Kumiko Inui+Tokyo University of the Arts Inui Lab, Little Spaces (TOTO Publishing, 2014). Photo courtesy of Inui Architects

Kumiko Inui+Tokyo University of the Arts Inui Lab, Little Spaces (TOTO Publishing, 2014). Photo courtesy of Inui Architects

Mohsen Mostafavi: What do you mean by symbiosis? Are you saying that your focus on the small spaces allowed you to understand the relationship between people and spaces, people and buildings, to understand in more detail how they use them in a way that’s very difficult with large developments?

Kumiko Inui: Yes. We selected scenes and spaces that were operated or maintained by the users.

Mohsen Mostafavi: What are some examples?

Kumiko Inui: Let me show you an example of a commercial area in Okinawa Prefecture. It is part of the public street, but shopkeepers use the street as part of their business area, and they keep that space so tidy. They use and maintain that space themselves. That is one example.

Space with multiple functions, Okinawa Prefecture (From Kumiko Inui+Tokyo University of the Arts Inui Lab, Little Spaces, TOTO Publishing, 2014)

In the example of Tosacho, the seawall is used as a kind of ad hoc space, and the users even put a roof over the seawall. They made the space themselves and adapted it to their needs. My research is about this kind of self-made space.

Small ad hoc space in shadow, Tosacho, Kochi Prefecture (From Kumiko Inui+Tokyo University of the Arts Inui Lab, Little Spaces, TOTO Publishing, 2014)

Another example is this very small hut that sits in front of the famous temple. In the hut there is a woman selling vegetables to the tourists, and in order to sell her product, she made and is maintaining this shade. I really like this shade because it’s very small, the size of a human. The shade and the woman are unified somehow. I think that is totally different from commercialized space.

Small kiosk in front of the Zensanji temple, Nagano Prefecture (From Kumiko Inui+Tokyo University of the Arts Inui Lab, Little Spaces, TOTO Publishing, 2014)

Mohsen Mostafavi: And this is what you mean by symbiosis?

Kumiko Inui: Yes.

Mohsen Mostafavi: So in this context, it seems like there’s a symbiotic relationship between the woman and her shelter and the space where she’s selling, and it’s very specifically designed for her needs.

Kumiko Inui: Yes, that can be called symbiosis. Let me show you another example. Here are some fishermen gathering between these pilotis, maybe relaxing after the morning session. They made their space by arranging the secondhand chairs, which might have come from a pub or a café nearby. Here, they can gather in a space away from their houses.

Space with large pilotis where fishermen lounge, Tosacho, Kochi Prefecture (From Kumiko Inui+Tokyo University of the Arts Inui Lab, Little Spaces, TOTO Publishing, 2014)

Mohsen Mostafavi: They can relax, it’s open and shaded and cool…

Kumiko Inui: The way they made their space is very free, and it looks very comfortable to me. And they didn’t pay any money to make this space—that is another point.

The last example is a very famous morning market in Kochi. Every Sunday in the center of the city, people gather to do business. The way they manage the businesses is very free, but at the same time, the market is maintained by the union of those people. That is another example of symbiosis.

Improvised space for the morning market in Kochi (From Kumiko Inui+Tokyo University of the Arts Inui Lab, Little Spaces, TOTO Publishing, 2014)

Mohsen Mostafavi: In your studies of Tokyo did you discover that some neighborhoods, some small communities, have a stronger concept of symbiosis than others? The reason I ask is because, many years ago, there was a group of people in Tokyo who started a zine about the neighborhood of Yanesen, trying to create a similar sense of consciousness and awareness in the community.

Now you are the one who knows about this symbiosis, and perhaps the people in the community are not conscious of it. I think the experiment in Yanesen was intended to make the citizens aware of the benefits of having a community. Because the community is disappearing—everything is disappearing in the big developments, so how to preserve that? Did you identify certain neighborhoods in Tokyo that still retain this strong sense of community?

Kumiko Inui: Yanesen is still one of the most charming communities. But there is also a strong community in Sugamo and Kishibojin near Ikebukuro. Even near Shibuya we have small communities. If we look closely, we can find lots of small yet active communities in Tokyo.

Mohsen Mostafavi: That’s great to hear. And now you are based in Yokohama, and I know that you have a new research project based on the question of the part and the whole. Why did you choose that? And why did you move away from the small scale?

Kumiko Inui: I think that modern planning-based urban planning is failing. And master plans are almost useless in this situation. However, we cannot leave everything to the market—we have to control it somehow. So urban planners and researchers point out the importance of incremental planning and simulation.

In Japan, which has entered a period of low growth, there are two distinct cases of urban expansion and contraction happening simultaneously. In such times I believe that an architecture project, even though it is a small point of development, must be connected to the urban and social issues that surround it. And this is why I focus on the part and the whole. I want to think about architecture and urban design at the same time.

I want to show you one example of my students’ work. This is a kind of Patrick Geddes section. The student tried to capture actors around an old building designed by Togo Murano. He drew an actor network around the building as a way of revitalizing it and the area around it.

Ryu Hanzawa, "New Parts and Whole," a proposal for a studio aimed at reactivating an old national masterpiece held by Inui at Yokohama National University, 2017

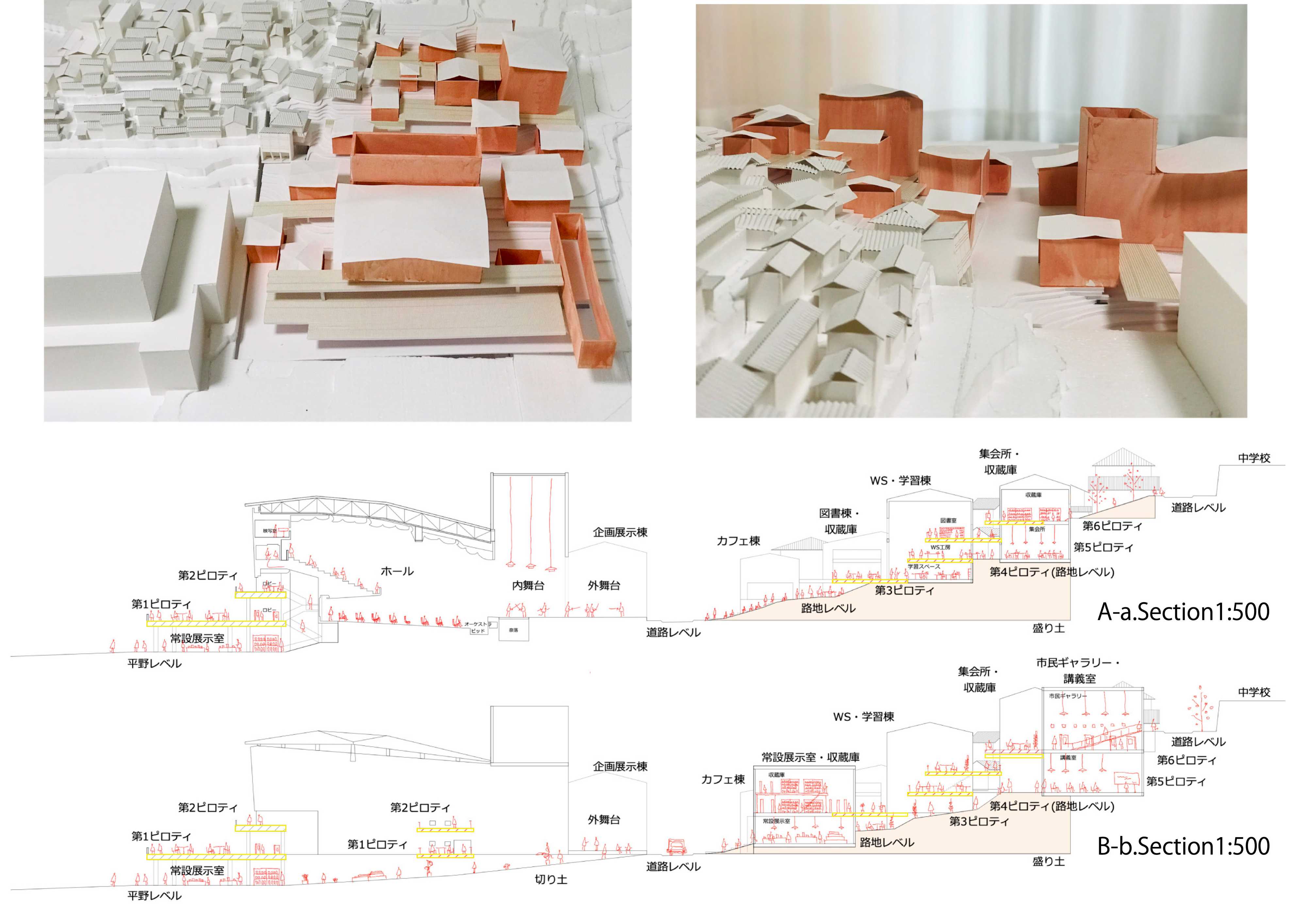

Ryu Hanzawa, "New Parts and Whole," a proposal for a studio aimed at reactivating an old national masterpiece held by Inui at Yokohama National University, 2017. Model and sections

Mohsen Mostafavi: I know that your interest in part and whole is connected to Dutch structuralism, is that right?

Kumiko Inui: Yes. The term “part and whole” comes from Dutch structuralism, but I am thinking more about urban design.

Mohsen Mostafavi: I’m interested to know why specifically you became interested in Dutch structuralism rather than, for example, rethinking Metabolism or some Japanese concepts.

Kumiko Inui: I think Metabolism is more concerned with production, with how to make buildings, whereas Dutch structuralism is more focused on the space and people. I started studying Dutch structuralism after I did the little-spaces research because I wanted to know about the relationship between space itself and building, the activities of people. I believe Dutch structuralism will give me some ideas about that relationship.

Mohsen Mostafavi: What kind of materials did you look at? What did you read?

Kumiko Inui: We have a few Dutch structuralism books in Japan. I read Aldo van Eyck in English and Herman Hertzberger in Japanese.

Mohsen Mostafavi: What do you see as the development of this issue of “part and whole” and the role of urban fragments? Where do you want the research to go?

Kumiko Inui: I want to think about the role of architecture in urbanization. Since urban planning is very difficult these days, making a building is a great way to redevelop an area. Of course, we have to know the area very well if we are to have a great influence on it.

Mohsen Mostafavi: Do you think that it is possible to make projects in Tokyo or Osaka—not single buildings, but rather urban design at a smaller scale—something different from what the big developers are doing with Rappongi Hills or Tokyo Midtown? Who would be the client? Would you need to work with the government, the state, the city, or would you work with small-scale developers?

Kumiko Inui: I think maybe the municipality, like Shibuya-ku or Shinjuku-ku—smaller-size government is the possible client. As I said, the railroad companies are also a possibility.

Mohsen Mostafavi: I ask because many of our friends are not working in the city anymore. Practices like Atelier Bow-Wow, for example, are focused on rural areas, where they can do more and have a more political voice. What do you think about this idea of people moving to rural areas rather than working in the city? They feel that politically it’s very difficult to work in Tokyo, but you seem optimistic with this part-and-whole research.

Kumiko Inui: I, too, feel that it is very difficult to do projects in Tokyo, but still there is a possibility.

Mohsen Mostafavi: Inui-san, this is very exciting work. Many congratulations on this research that you’re doing and also on your investment in infrastructure in small communities in Japan. Do you have some last words you want to share with us, any ideas or recommendations for our research?

Kumiko Inui: The other day, in a seminar with my students, I picked up Ivan Illich’s Tools for Conviviality. I think that notion is great to think about.

Mohsen Mostafavi: I’m so happy that you mentioned this. You know, I met Ivan Illich a long time ago, and he was a great friend of my teacher. I’m pleased that his work is read and discussed in Japan today because I think it demonstrates a very specific interest on your part in the role of the people—how to bring their voices in and create an architecture that is accommodating. Today there’s also a lot of interest in the topic of hospitality, and I see some parallels between conviviality and hospitality—the sense of the city as a site of welcome and a place that can host many people.

Inui-san, thank you so much for taking the time to talk to us tonight.

Kumiko Inui: Thank you very much. Good night.