Alone Again, Or: Two projects exploring life in Tokyo’s evolving fabric

Mohsen Mostafavi: Thank you for joining me today, Maki-san. I read your book, City with a Hidden Past.1 It was very kind of you to send it to me.

Fumihiko Maki: Yes, that has finally been translated into English.

Mohsen Mostafavi: Very interesting, very important. When you did the book, how did you collaborate with your colleagues in the office? They contributed valuable and informative essays about the street, about micro-topography…

Fumihiko Maki: You know, in Europe the old master just made the design, and his apprentices implemented his vision. But at the Tange Lab, in which I took part, it was different.2 Tange would decide we should have a discussion among key persons, including himself, and led the discussion. It was an open discussion, and the final decision was made by him. In this way, many ideas came from the elders as well as from younger people. I’m more or less in favor of this system.

Mohsen Mostafavi: An open collaboration regardless of hierarchy?

Fumihiko Maki: Yes.

Mohsen Mostafavi: Do you still work like that?

Fumihiko Maki: Yes, we still do that, but now younger people are taking the initiative because their ideas are better than mine.

Mohsen Mostafavi: Okay, I don’t believe you.

Fumihiko Maki: It is true.

Mohsen Mostafavi: But you’re still doing some research with the office?

Fumihiko Maki: Yes, I don’t exactly go and do research, but the exploration.

Mohsen Mostafavi: Do you call City with a Hidden Past an exploration?

Fumihiko Maki: Yes, a collaborative exploration.

Fumihiko Maki, Yukitoshi Wakatsuki, Hidetoshi Ohno, Tokihiko Takatani, Naomi Pollock, City with a Hidden Past (Tokyo: Kajima Institute Publishing, 2018)

Mohsen Mostafavi: I want to build on what you did with your book, which is about the history of Japanese urbanism. It would be interesting to analyze the present situation and also make some proposals for the future based on current conditions as well as what we can learn from the past.

For example, I notice that a number of Japanese architects have decided to give up on the city. It’s only the development companies and the railway companies that are dealing with the city. Why is that? Why is it that now it’s not possible for architects to think about the urban condition?

Fumihiko Maki: I call them atelier-type architects. They have fewer opportunities to do a large-scale development, and that’s the reason why some people are not committed to large cities like Tokyo, Osaka. This is truly a trend, but as you know, we have maybe a dozen large, corporate architects’ offices like Nikken Sekkei. They are doing many large-scale urban development projects, so architects are being divided into two groups: the boutique type and the more corporate, large-office type. They have different prospects in dealing with even large-scale projects.

Mohsen Mostafavi: I understand. But just in thinking about the atelier type or the small design practice…when you were starting out and didn’t have a big office, you still thought about big projects.

Fumihiko Maki: Sure, we were able to do that.

Mohsen Mostafavi: But now?

Fumihiko Maki: But now, not so much.

Mohsen Mostafavi: And not so many architects are making a vision for the future, though an increasing number seem interested in the suburbs and the countryside. What do you think are some important questions for the Japanese city, for Japanese urbanism?

Fumihiko Maki: I think that urbanism used to be everybody’s concern and interest in the 1950s and 1960s, but not anymore. And this is not just in Japan.

Mohsen Mostafavi: That’s why I’m very interested in doing a new kind of research, collaborative research. Not only focusing on architects or developers but also on the railway companies, artists, writers, and photographers.

Fumihiko Maki: You know, in the 1950s, we had Kevin Lynch and also a few others you’ve heard of, a very strong group. But that period is gone. Today we don’t find any well-known architects or writers addressing the big urban questions.

Developers are just interested in making money quickly. That’s all, and I think many architects follow this trend without any criticism anymore. They’re just glad to have a commission. That’s my observation worldwide—it’s true not only in the United States but in Europe as well. I don’t know, I’m 92 so I don’t have too much time left for studying or participating in this area that interests you.

What you are saying is right, but the question is, who would direct these capitalistic forces? Who would do that kind of research? Maybe the universities.

Mohsen Mostafavi: I think the question is whether it’s possible to create some contact between designers, developers, who have a special role in Tokyo—construction companies, and so on.

If we look at the voice of the architect as a form of engagement in the urbanism of Tokyo, you made a very important public statement about the new stadium for the Olympics. Your comments had a lot of influence in shaping public opinion about the role of scale.

Fumihiko Maki: I wrote a very critical comment in response to Zaha’s scheme for the Olympic stadium.3 Now the new scheme has come in,4 but again, it is still a large gymnasium in a densely populated place. It’s a big issue, not for the Olympics but after the Olympics.

In Beijing, if you don’t want to see the stadium, you don’t have to see it because there is a big open space between the place where you are walking and the gymnasium itself. But in Japan, this new stadium is in a crowded place. In Tokyo, you are forced to be near the big stadium. I went to see it and it’s so big.

I’m more concerned with what happens post-Olympics. The event may succeed in entertaining people from abroad, but after the Olympics, what are you going to do with the stadium? There are security concerns, for one. When you go to the Louvre, there’s no problem because people are constantly going into a basement and enjoying all kinds of stuff, but this will not happen in the new stadium because the use is sporadic. Only once a month or so—it wouldn’t be an animated process.

You can’t make money on it, so no private companies are interested in taking it over, and therefore the Japanese government must keep it. But the government may not be able to keep those big facilities for long either, given the costs of maintenance and landscaping. That is one of the big problems we are facing.

But a more important issue is that we are losing population and also income for the country. The big mistake of having such a huge stadium in a very crowded city like Tokyo signifies problems we are going to face in the next 10, 20, 30 years. What I think gives better prospects for the future is the many small ideas that we have and can be realized in the city.

Mohsen Mostafavi: I’d like to ask you about the “small ideas” in detail, but for the moment, let’s stay on the topic of large-scale development. What do you think about the types of projects that the developers are creating? I mean the buildings that are only for wealthy people. In new large-scale developments, there are buildings that ordinary citizens of Tokyo cannot really go inside. For instance, in Tokyo now I don’t see a good example of a mixed-use development that is also for the middle- or low-income families. They have to go outside the city. This is a trend in so many cities around the world.

Fumihiko Maki: Yes, this is true. If you want to have good urban places for the middle class, it is a big problem.

Mohsen Mostafavi: I think that Tokyo is becoming a place for wealthy people, and the contemporary design—new design—in Tokyo is invariably for the wealthy. Do you know any developers who are doing something…a little bit more experimental, unusual, and yet affordable?

Fumihiko Maki: I don’t think so.

Mohsen Mostafavi: What do you think about the demolition of some buildings in Tokyo or in other Japanese cities? For example, the Tsukiji Fish Market holds a very important place in the collective memory of the people of Tokyo even when they had not visited the market for a long time.5 Tsukiji is like a monument that has disappeared—but its memory remains, as does the sense of longing for the experience of the auctions and the early morning taste of a good sushi.

Tsukiji Fish Market (1935) photographed early in the morning, 1962. Photo: Mitsuo Sakayori. Courtesy of Chuo City Kyobashi Library

Fumihiko Maki: I understand they’re trying to do some redevelopment on the site of the old fish market, but we just have to wait and see if they are successful. It’s too early to make any judgments.

Mohsen Mostafavi: But now that the market has disappeared, and people will not be able to visit it, a very important part of the memory of the city will also disappear. It’s like erasing the memory, a common memory.

Fumihiko Maki: Not only memory. As I said, we are facing the problem of declining population. And Japan is a very closed society that accepts far fewer immigrants than Western countries. In the newspaper this morning I saw a report about old people today who live into their 80s, 90s, and beyond without having much money for retirement. So we have to have a strong public policy. But, unfortunately, I don’t have much faith in the current politics or politicians.

Mohsen Mostafavi: If we look at the map of Tokyo, different parts of the city are owned by different developers—Mitsui owns part of Nihonbashi, Mori part of Roppongi and Azabu, and so on. The city belongs to private owners—I call these private empires.

Areas for deregulated urban development (Urban Renaissance Urgent Redevelopment Areas) in Tokyo designated by the national government, 2018. Source: The Cabinet Office, Tokyo Metropolitan Government

Do you know that London was developed because of the way the king gave land to different members of the royalty for their estates, like Bedford Estate and Grosvenor Estate? Tokyo is doing something similar now. In London, different neighborhoods were developed by people who were wealthy, connected with the king. In Tokyo now, the city is also, in effect, owned by these developers. Would you say that the city is becoming privatized?

Fumihiko Maki: Yes.

Mohsen Mostafavi: I agree. If Mitsui and Mori own big parts of Nihonbashi and Roppongi, respectively, then these areas are indeed becoming privatized. You can still go to Roppongi Hills, for instance, but you know that it’s also private in terms of ownership.6

Fumihiko Maki: You’re probably right, but the question is, how far will the Mori people or the Mitsui people be able to extend their reach? I don’t know.

Mohsen Mostafavi: One other observation I made is that, in Tokyo, most large-scale developments are only along the main street, and the relationship between old and new is very close. Behind a large-scale development there is often a low-rise neighborhood and you still have old Tokyo. The new development is almost like a stage set because it’s only in the front. It creates a stark scalar contrast between new and old.

Fumihiko Maki: Yes, and that’s a problem. You see, the Japanese building height and FAR [floor-area ratio] are decided by the width of the frontal street, and when you have a big street, you have greater height and FAR. Barrie Shelton made a very interesting diagram of an isometric, which shows typical Japanese development situations. The developer doesn’t touch inside large streets because it would mean negotiating with all the landowners. It’s too much of a problem, and also it doesn’t allow you to have a big development. Developers are only interested, as you said, in development along the large street.

A typical condition in large cities in Japan as a result of development. From Barrie Shelton, Learning from the Japanese City: Looking East in Urban Design (London: Taylor & Francis, 2012)

Mohsen Mostafavi: Take Omote-sando, a commercial district, for example. On the front street, you have big boutiques with the fancy image of fashion brands, but in the back it’s suddenly small-scaled.

Fumihiko Maki: Yes, exactly. Those are the jobs for small, atelier-type architects.

Mohsen Mostafavi: Hillside Terrace, which you started in 1969, stands in sharp contrast to the current development trends we’ve been discussing. What are your thoughts now when you look back on that project? And, given its longevity and its popularity, why aren’t there more Hillside Terraces in Tokyo?

Fumihiko Maki: At Hillside Terrace you have a large street like many others. Kikujiro Asakura, the founder and the grandfather of the current developer, didn’t want to have high-rise and large-scale development, so he kept the place for lower height and lower FAR. Hillside Terrace is a unique place.

Mr. Asakura decided to have a much wider street, and he gave some of his properties to make this street wider. But, at the same time, some politicians didn’t want to have this kind of large development, so we kept the places to be lower height and lower density. Therefore, as you walk, you can find these very relaxed sort of open spaces just inside this wide street. So we are very lucky to have this kind of situation.

The development of Hillside Terrace, built in six phases from 1969 to 1992, and the Royal Danish Embassy, all designed by Maki and Associates. Photo © ASPI

Mohsen Mostafavi: I agree, but it’s a new typology that doesn’t exist anywhere else.

Fumihiko Maki: Yes, because now in Japan, everybody wants to have a higher FAR. And nobody ever asked me to do anything similar to Hillside Terrace. I assume that the condition is very difficult to satisfy—a large street and low densities. That combination is something that developers in Japan always avoid. They like to have a higher FAR, but I think the time has come to have something more like Hillside Terrace in Japan.

Mohsen Mostafavi: I think that the incremental development on the wide street in Daikanyama has been very successful.

Fumihiko Maki: Sure. Mr. Asakura, the current developer, said if an earthquake destroys it, he’s going to make one exactly like it.

Mohsen Mostafavi: But why did he make it incremental?

Fumihiko Maki: I don’t know, but at least it makes a very nice extension. Hillside Terrace is becoming more active and more alive, and I was very happy with what they have done.

Mohsen Mostafavi: Did you ever design a denser version of Hillside Terrace? For example, I could imagine a design with the same Hillside Terrace, but maybe six stories and four stories instead of three stories.

Fumihiko Maki: I haven’t done that yet because I only do things when somebody else asks me to do them. I don’t look beyond that. Could you make Hillside Terrace in other places? That is a good question.

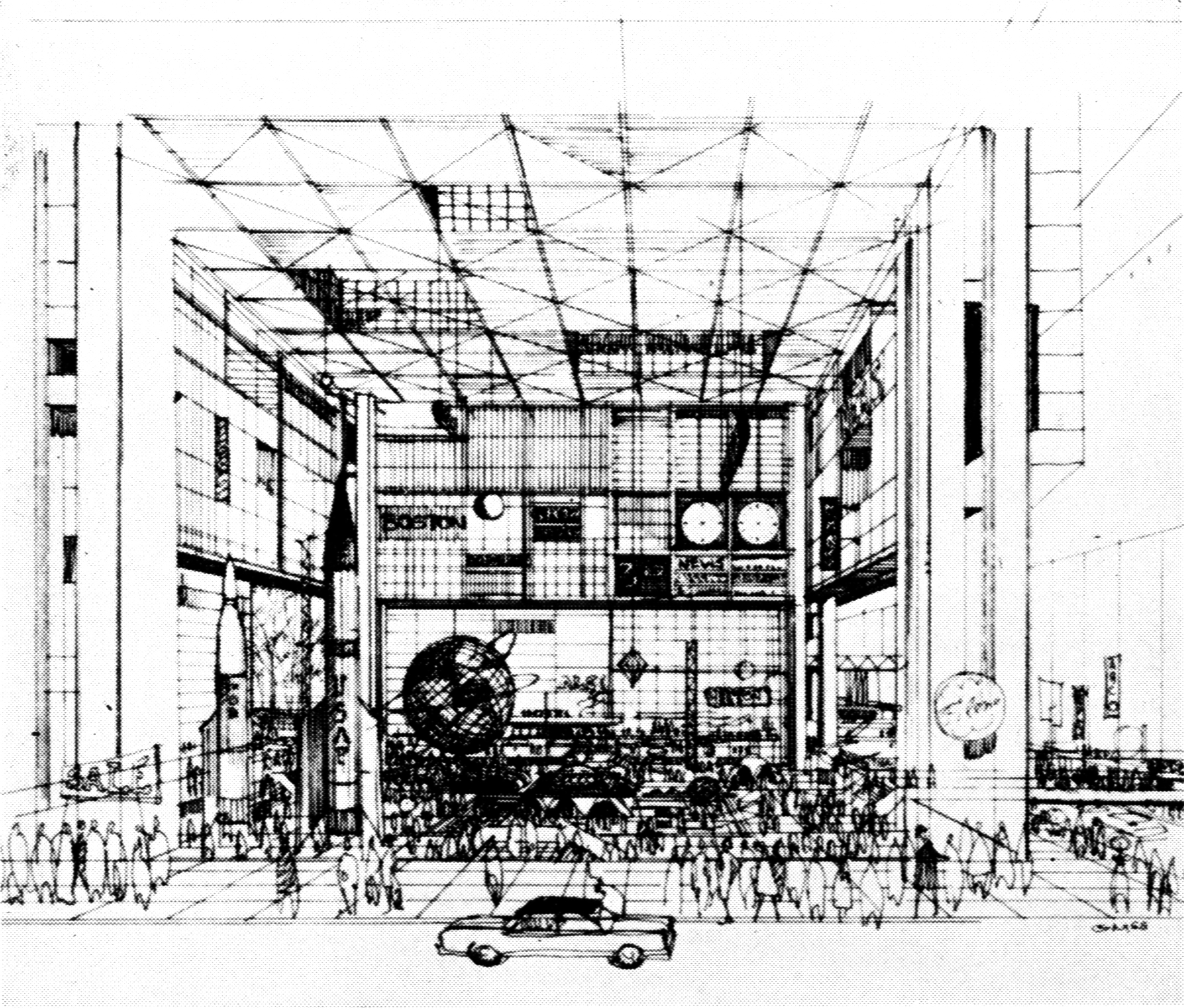

Mohsen Mostafavi: But, for example, when you were at Harvard, you thought about the idea of the “city room.”7 You didn’t have a client. You just had the idea.

Fumihiko Maki: Yes, in my 60 years of practice I was fortunate to just do whatever people asked me to do. I don’t plan and then try to sell the idea to others. But I have a fairly clear understanding of the problems and prospects and possibilities for Japanese cities because I was teaching.

Fumihiko Maki, City Room (part of the “Movement Systems in the City” proposed for the city of Boston as a traffic network plan), 1965. Perspective drawing. Courtesy of Maki and Associates

Mohsen Mostafavi: If you were doing a research project now or a studio about Japanese urbanization, the Japanese city, what would you do? What do you think should happen to the Japanese city?

Fumihiko Maki: We used to keep a small presence in the city, because Japanese are always concerned with a minute sort of environment, and I think this is also the strength of Tokyo and Japanese cities. When you go inside, you have many interesting sorts of places, and people just don’t give up or make a place desolate. Instead, they are still trying to keep places neat, quiet, and interesting.

Mohsen Mostafavi: But you also worked out a strategy for dealing with a large-scale project in Tokyo. You designed Tokyo Denki University. It has a large open space for the public.

Fumihiko Maki: We have also done work at MIT and the University of Pennsylvania, but in Tokyo it’s a fairly large development.

Mohsen Mostafavi: What do you think is the main philosophy for Tokyo Denki University?8

Fumihiko Maki: It’s very free.

Mohsen Mostafavi: Barrier-free?

Fumihiko Maki: Yes, meaning no gate, no walls, and people are able to go freely through the campus. Another interesting thing is that children can come into the place. Teachers bring children, and they enjoy places like this.

You know, the most interesting thing is individual behaviors and desires. Some of those behaviors and desires make a city. You can’t just use statistics. Millions of people’s desires and behaviors make a city, that is true.

Maki and Associates, Tokyo Denki University, Tokyo Senju Campus Ⅰ-Ⅱ, 2014–2017. View from above. Photo ©Toshiharu Kitajima

Maki and Associates, Tokyo Denki University, Tokyo Senju Campus Ⅰ-Ⅱ, 2014–2017. The large open space in the campus has become a favorite place of the neighbors. Photo ©Toshiharu Kitajima

Fumihiko Maki et al., City with a Hidden Past (Tokyo: Kajima Institute Publishing, 2018). This is the English translation of the book originally written in Japanese and published by Kajima in 1990. The book is an anthology of explorations by Maki and the staff members of his studio into how the urban composition of Tokyo has been formulated and transformed since the Edo period. Maki’s discourse on inner space (oku), Takatani’s analysis of the enduring impact of the street structure underlying the city, and Ohno’s insight into the layers of space mediating houses and the city, among other chapters, continue to inspire readers today.

Maki belonged to the lab when he was a student at the University of Tokyo.

Maki’s position statement was first published in the August 2013 issue of the JIA Magazine, a monthly of the Japan Institute of Architects, under the title “Thoughts on the New National Stadium Proposal in the Historical Context of Jingu Gaien.” It immediately created a polemic, which spread across the country.

At the time of the interview (December 2019), the stadium based on Kengo Kuma’s proposal was under construction. His proposal won the second competition, which was held after the first design, by Zaha Hadid, had been canceled.

Since its construction in 1935, Tsukiji Market played a significant role not only in supplying quality fresh food but also in enhancing the particular food culture of the country. But because traffic was congested and the buildings were becoming too small, the market was relocated farther east, to Toyosu, in 2018. Before the relocation, the market was one of the most popular tourist destinations in Tokyo.

In 2002, the Japanese government enacted the deregulation policy for urban development in Tokyo and other large cities, and in doing so, they delegated planning and managing development to consortiums of major developers.

Maki invented the concept of “city room,” which he included in his “Movement Systems in the City,” proposed for the city of Boston as a traffic network plan in 1965. The “city room” was conceived as an urban space unit that works as a node of channels of transport and activities.

The Senju campus of Tokyo Denki University, built in 2017, was designed by Maki in such a way as to help regenerate an old town surrounding the campus and the Kita-Senju station in the east of Tokyo. In an effort to share the space with the neighbors as much as possible, the campus includes wide open space, a nursery, fab labs, and learning support facilities, all of which can be accessed by local residents.