Chapter III: Methods of Spatial Composition

Japanese spatial constructs are somewhat hard to grasp by the actual end results of their formative processes. Since these spaces are replete with symbolism, subjectivity, extrinsic affinities, and innate indeterminacies, mere study of the material forms is inadequate. Of course, this is not to say that we cannot discern any spatial order, but rather that we must apprehend them as distinct non-materialized stages in the formative processes—i.e., as functional, structural, and symbolic stages.

Going forward, let us consider these various stages by looking at several significant ideas from the past to see how they serve as general compositional principles that bring order to spaces.

Four concepts that help frame the spatial “hardware” include:

Four more qualitative or cognitive concepts that we may add include:

Noh theater. Photo: © Osamu Murai

Spaces are not composed solely of material elements. As a rule, spatial creations always comprise expressive portions and blank portions, the overall meaning consisting in the interplay. One distinctive feature of Japanese spaces is the blurring and accentuation of these blank portions; expressive portions often draw attention to otherwise empty, “unseen”1 intervals, nonetheless seen as integral to the total space.

Such blank portions are called ma in Japanese. Concepts of ma permeate Japanese thinking and figure in many colloquialisms, for example, ma motanai, “loose” (lit., cannot hold ma), ma nuke, “dumb” (lit., neglecting ma), ma nobi, “delay” (lit., extended ma), or ma chigai, “error” (lit., misplaced ma).

By way of example, in the game of Go, the act of placing a stone serves to assert one’s area of control one or two places (ma) around it. The basic idea of Go is that only the empty places demarcated by the stone count as territory—the stone itself does not. Likewise, in residential architecture, rooms are referred to as ma, for example, cha no ma, “family room” (lit., ma for tea), or ima, “parlor” (lit., ma for residing). That is, rooms are customarily named not by their material components, but rather as voids whose functions or purposes manifest and are recognized through the addition of material elements.

Furthermore, adding or removing such modifying elements can change the very meaning of spaces, or shape a whole new material space. In this sense, these material modifiers may even be regarded as temporary elements and not integral to the space as a whole.

The four posts of a noh dance-theater stage once supported the roof of the stage but have since been subsumed into a symbolic role. The posts lend a sense of orientation to the stage, so that the actions of performers take on different meanings depending on which post they face. Moreover, we can generally picture the layout of Japanese houses, temples, and shrines merely from the placement of columns that serve as mediating skeletal elements between which various ma manifest.

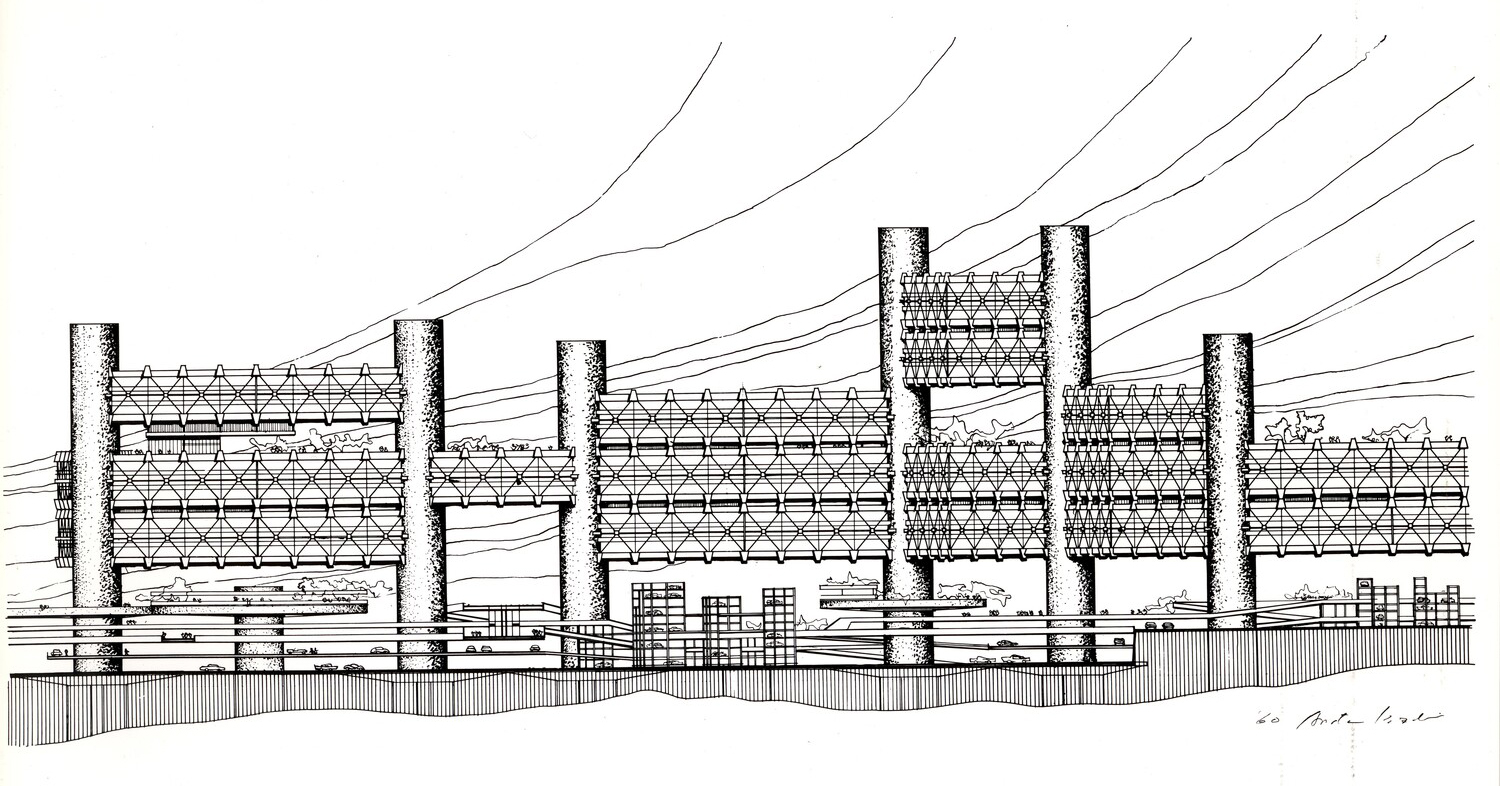

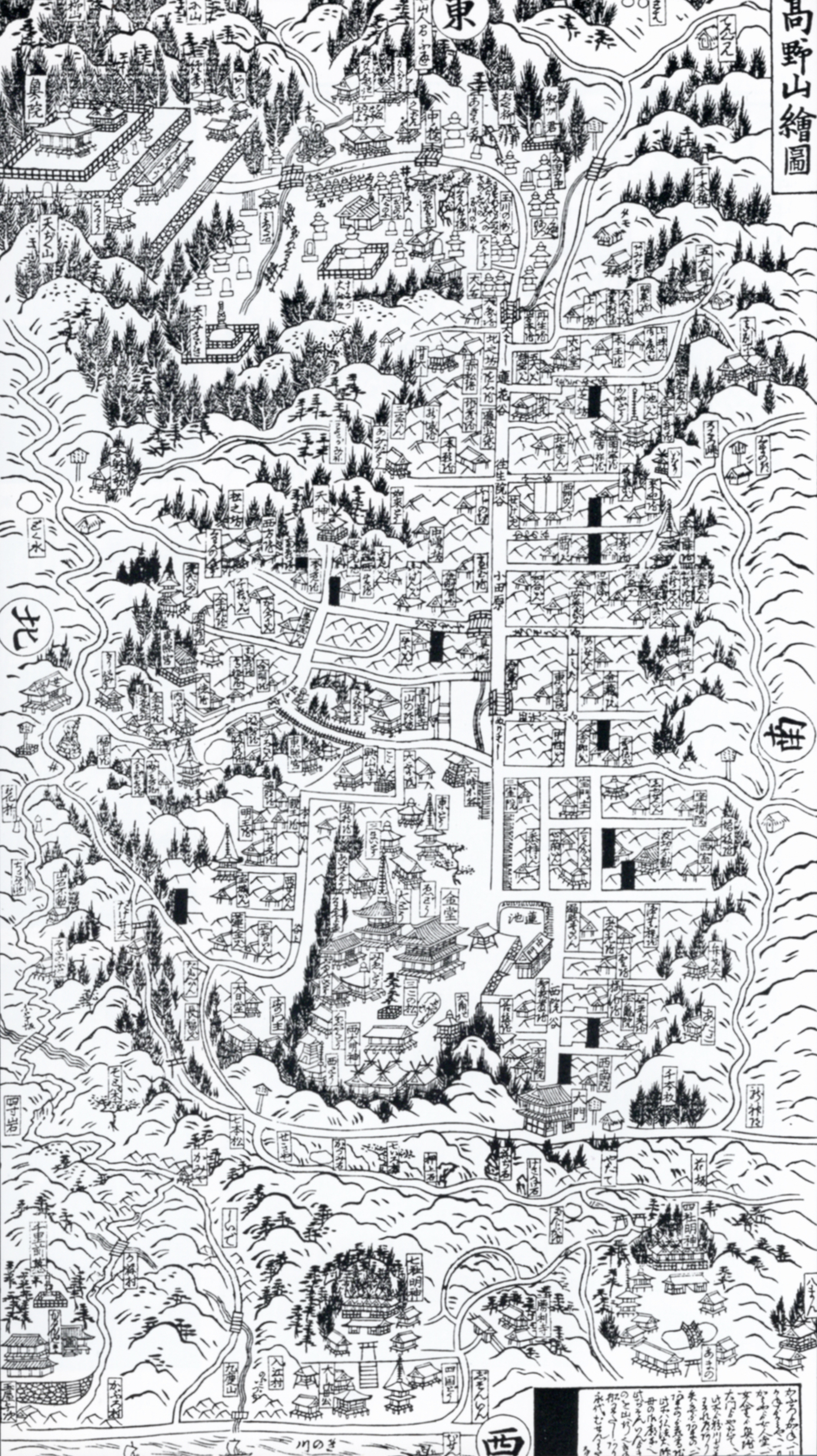

The notion of establishing a skeleton for ma by means of column foundation stones can be used in urban planning, as seen in the proposed Shinjuku Project.2

Even a single column can generate ma. The sacred central column (shin no mihashira) of Ise Shrine is both the very basis of the shrine’s architecture and a symbol of the kami divinity, thus creating a special space all around it, which is reified by spreading gravel as a modifying material.

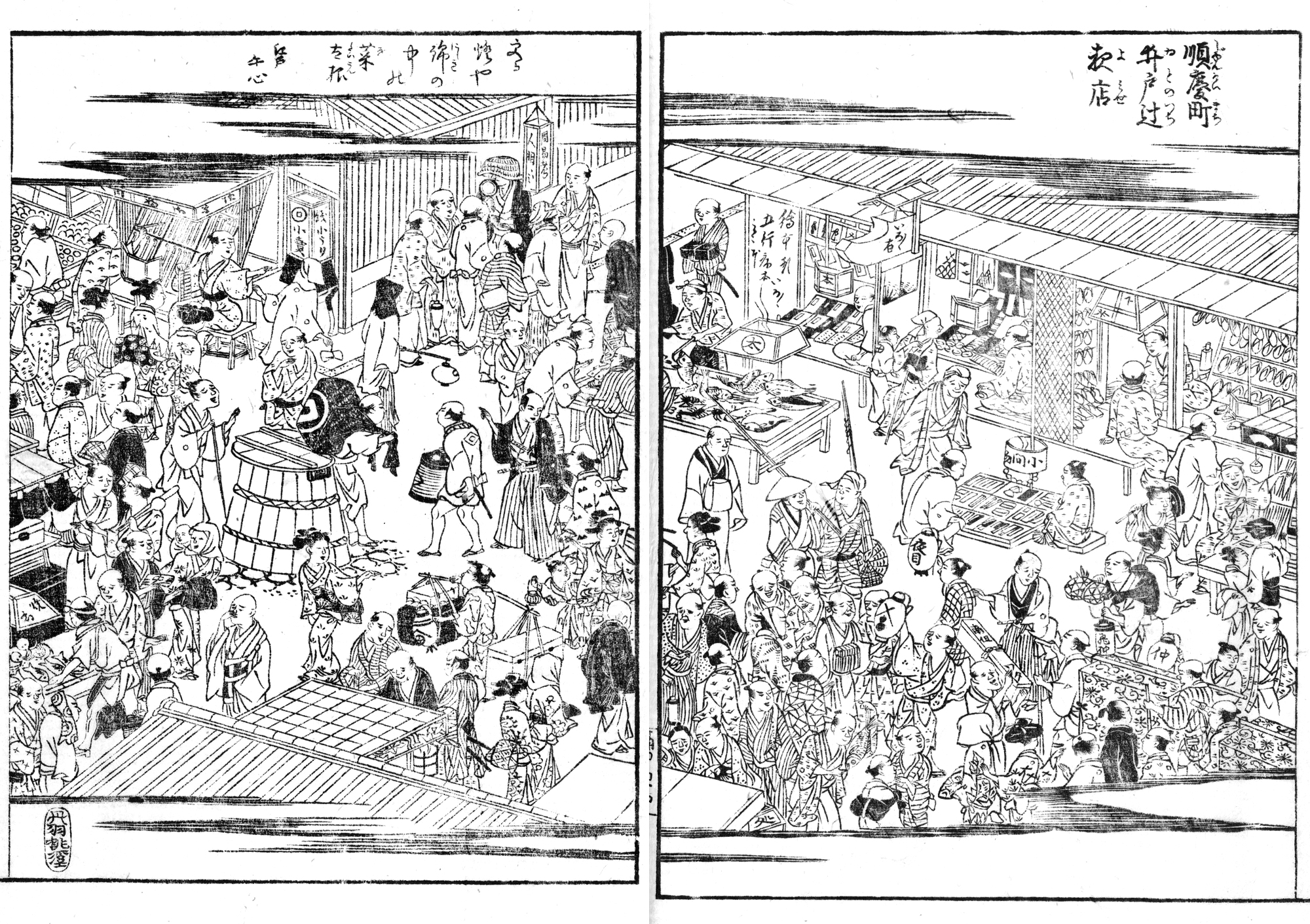

Rice transplanting in Rokushonomiya, Edo, from Edo meisho zue [a series of geographical booklets illustrating the scenic places of Edo {Tokyo}], 1834–1836

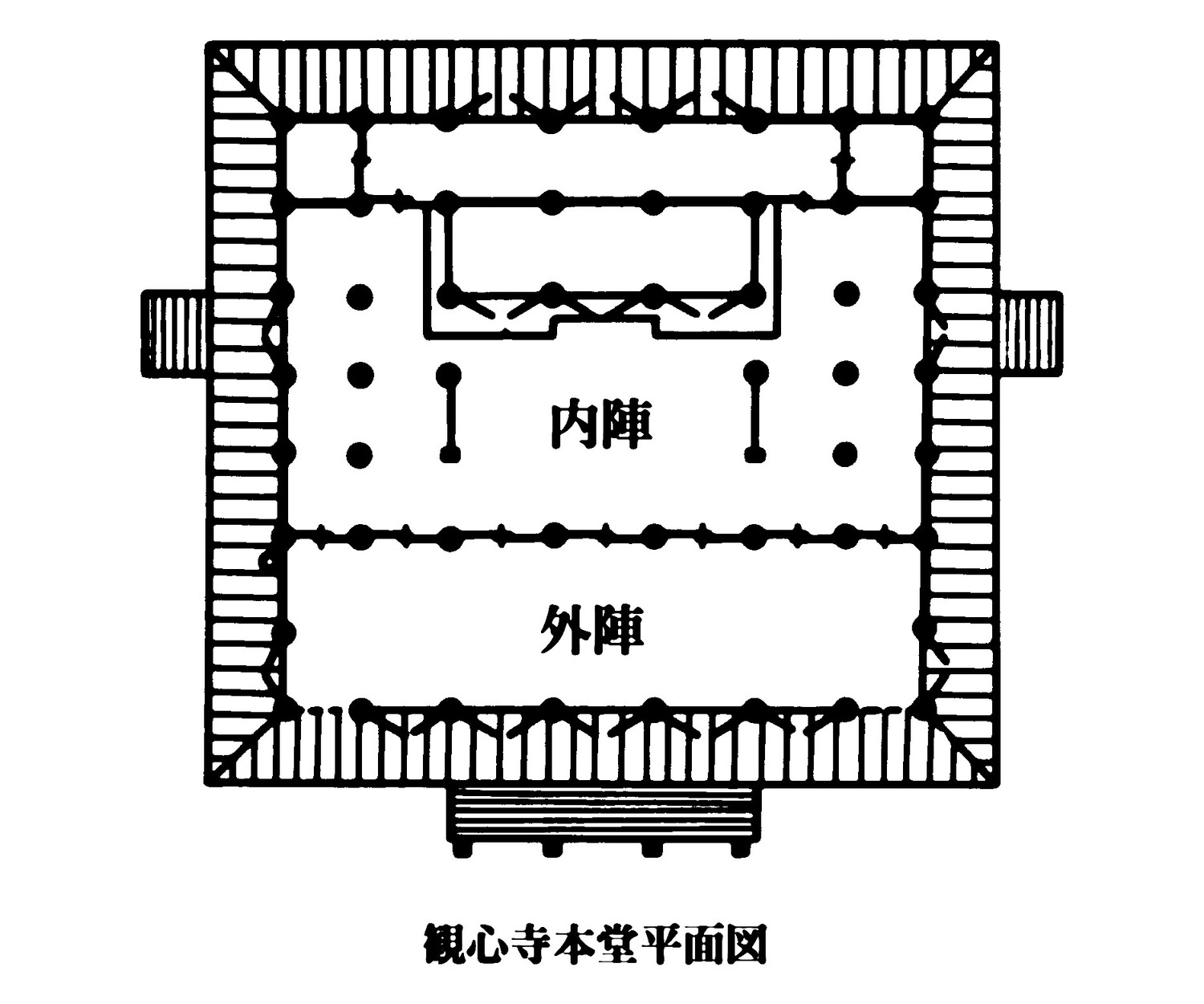

Kanshinji temple. Plan of the main hall. Kawachi-nagano, Osaka

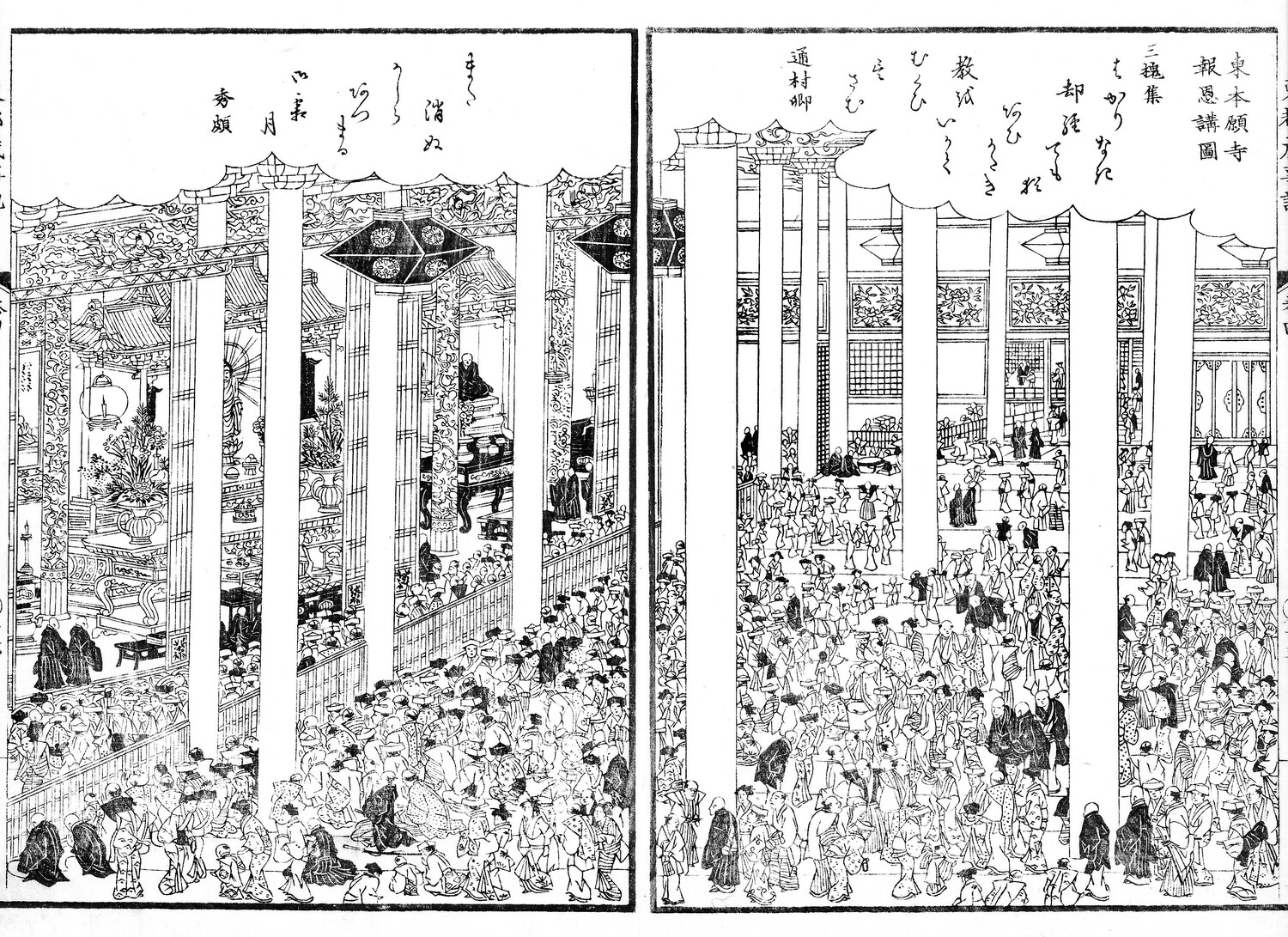

Memorial service at Higashi Honganji temple, Edo, from Toto Saijiki [an illustrated catalog of season-specific events throughout a year in the eastern capital of Edo {Tokyo}], 1838)

Arata Isozaki, City in the Air (Shinjuku Project), 1960. Courtesy of Arata Isozaki and Associates

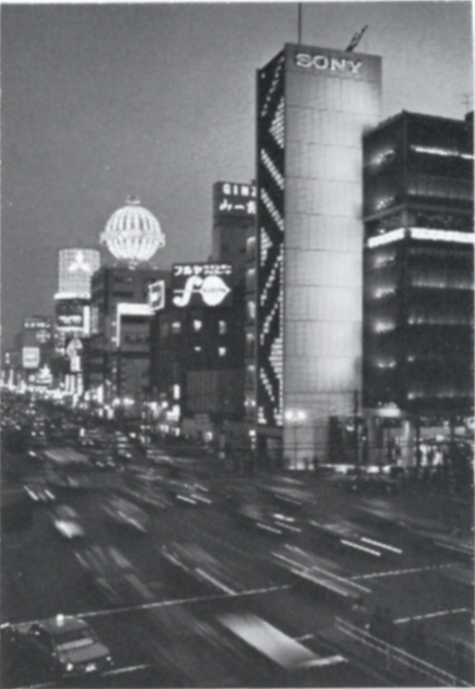

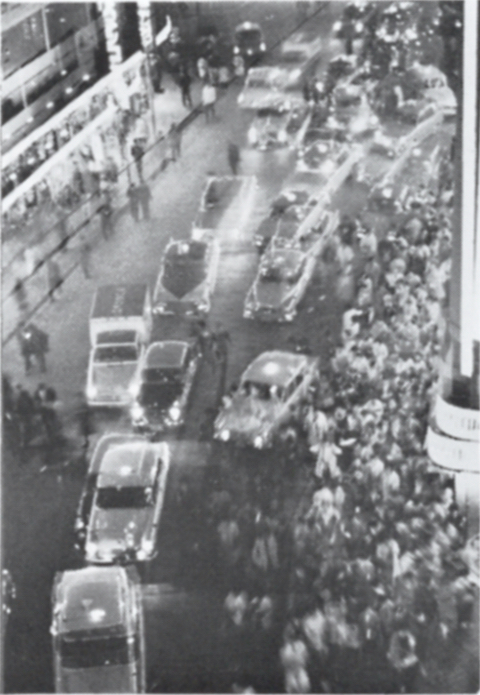

Whether we’re talking about Shijo in Kyoto, Ginza in Tokyo, or Minami in Osaka, which are more than just geographic “districts” or connective “avenues,” these names conjure up hotbeds of hustle and bustle in the city. Perhaps the most apt term in Japanese to describe such urban living spaces is kaiwai.

Kaiwai denotes a cumulative mass of individual human activities or, alternatively, an accumulation of facilities that promotes human activities. When we speak of such and such a kaiwai, we summon up a collective image shaped by personal experience, not limited to any physical configuration. Nor will such an assemblage of mental images necessarily coincide from one person to the next.

While we may have in mind one particular destination in the area, the kaiwai will also include various other facilities of similar or complementary function. Cinemas or cafés can, for instance, offer otherwise unrelated continuations of the day’s activities.

Likewise, new ventures can take advantage of the collective liveliness of these places, be they newly launched premises or pursuits that offer new options or completely spontaneous activities suggested by the local atmosphere.

Kaiwai environments characteristically combine many different intended and unintended activities and typically grow organically, without any predetermined physical core. No one single facility can be said to play a decisive role in shaping the kaiwai. The spatial contexts may be fairly constant, but the outlines are always hazy, making it impossible to say just where the kaiwai boundaries lie. Which is only to be expected, since it is an accumulation of individual activities.

As should be clear to anyone walking from Shimbashi toward Kyōbashi, there are many Ginzas. One kaiwai can comprise a number of distinct kaiwai that interpenetrate and overlap. If pressed to ascribe physical dimensions to a kaiwai, the simplest way would be to take a little walk from what seems to be the center and come back. Anything near can be said to be a kaiwai. The practice of urban design calls for techniques to integrate such kaiwai spatial units into a city.

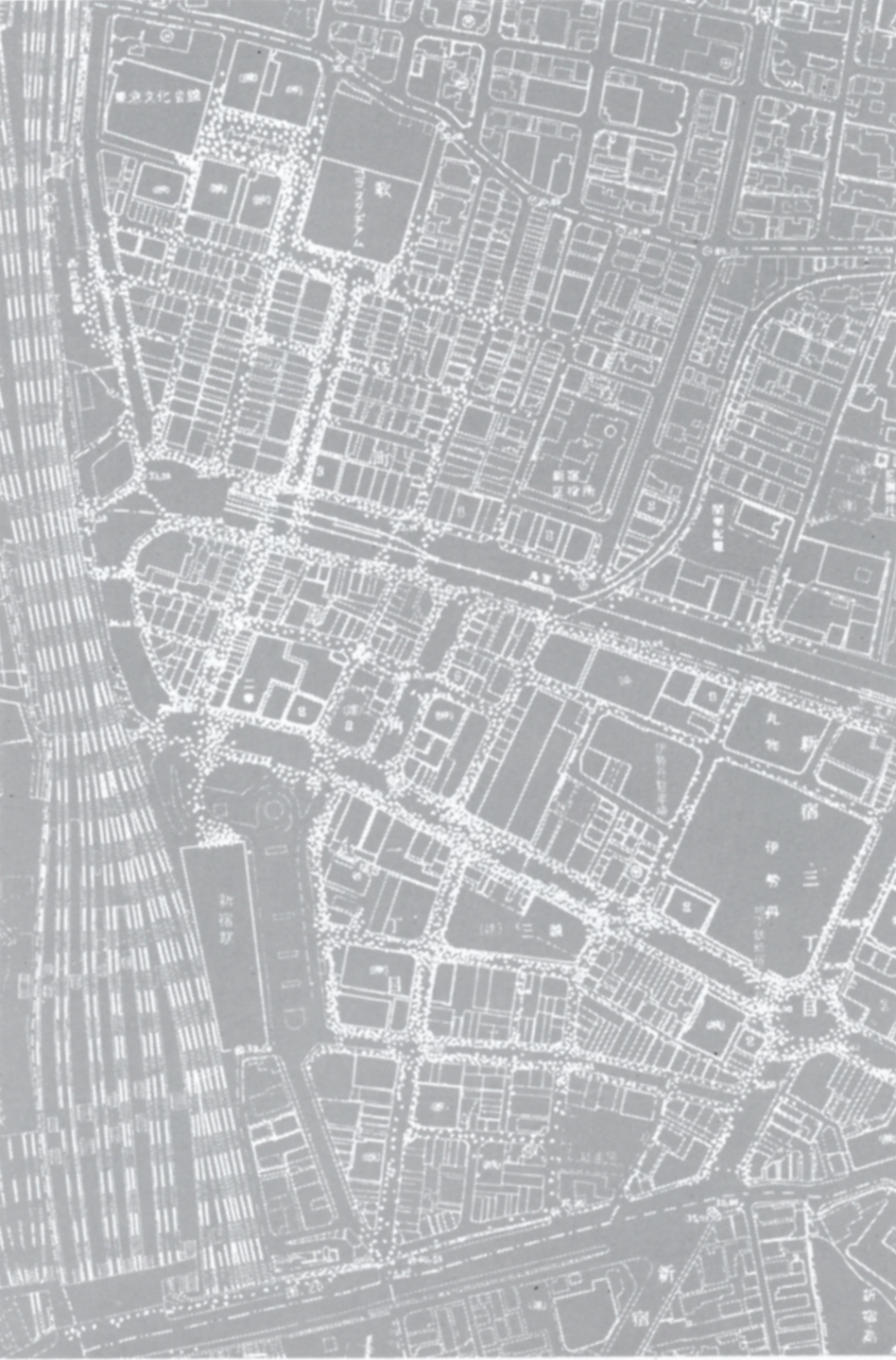

Ginza kaiwai

Population density in the Shinjuku kaiwai

Shinjuku kaiwai (by day)

Shinjuku kaiwai (by night)

Night market at the crossing with a well in Junkeimachi (Osaka), from Settsu meisho zue, Vol. 4, published in 1796–1798. Source: National Diet Library

The translation of the parts of Nihon no toshi-kukan [Japanese Urban Space] was made possible by courtesy of the publisher. Nihon no toshi-kukan was written by Toshi-dezain kenkyutai [Research Group for Urban Design], edited and published by Shokokusha Publishing Co., Ltd. in 1968.

Translator’s note: “Unseen” is intended as a paradox. In Japanese architecture and design, open and unfilled ma elements are always given considerable conscious attention. Otherwise invisible spacing is regarded (hence actually seen) as contributing the greatest aesthetic and utilitarian qualities to spatial configurations.

Also named “City in the Air.”