Chapter II: Principles of Spatial Order

When bringing together buildings and natural features as compositional elements in spatial configurations, a certain degree of visual unity can serve to create spaces that suggest special functions or symbolic importance.

Here, we shall consider various concrete methods of composition to realize such spaces. In general, continual activities give shape [and character] to spaces, with axes of motion arising in the process. Streets are among the most important axes, typically bordered by townhouses much like hallways lined by physical objects, though there are many other kinds.

Axial approaches to shrines and temples afford a clear view through surrounding obstacles, functioning less as dividing lines between distinct areas than connectors between internally related elements. Even those “hallway” streets between houses tend to create very organic connections between elements as a type of extended living space.

We should note that the [thirteen] methods described here all relate by greater or lesser degree to activities:

Random scatter (あられ arare)

Branched clusters (千鳥掛け chidori-gake)

Alternating turns (折れ曲がり ore-magari)

Stressed bends (歪み hizumi)

Indenting (凹み kubomi)

Offset corners (隅違い sumi-chigai)

Cross-corners (隅掛け sumi-gake)

Obstructing (障り sawari)

Allusive detailing (盗み nusumi)

Borrowed backdrops (生けどり ikedori)

Steep and gentle slopes (男坂・女坂 otoko-zaka onna-zaka)

Half-hidden views (見えがくれ mie-gakure)

Intermittency (ひもろぎ空間 himorogi kukan)

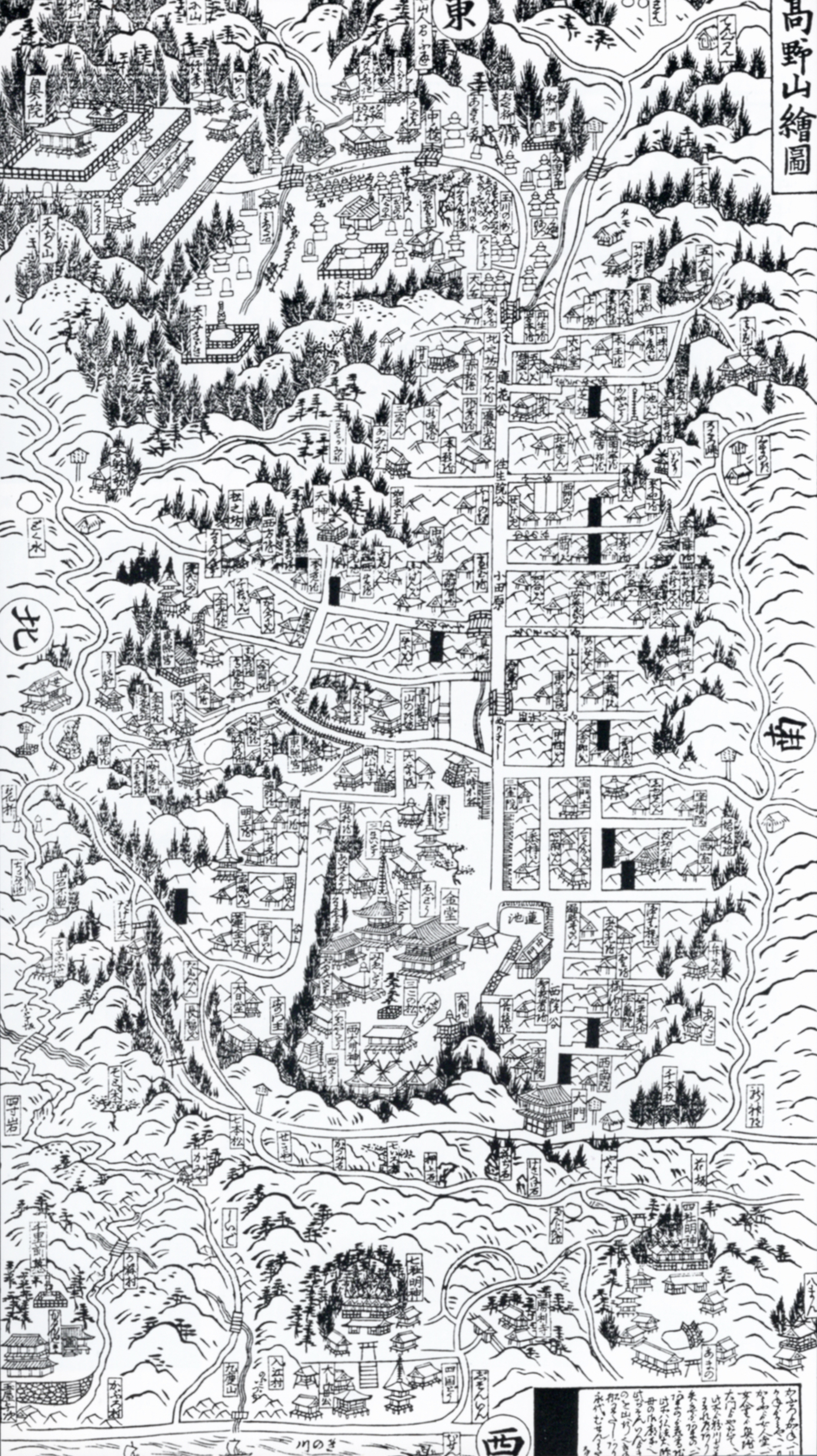

Koyasan zue [pictorial map of Mt. Koya, a sacred place for Buddhist pilgrims], 1810

As a method, ore-magari (literally, fold-and-turn) consists of multiple changes of direction in the axis of activity. The simplest example might be Hozenji Yokocho, a famous lane in Osaka that bends twice sharply to interconnect a traditional cobblestone walkway past a small shrine with a neon-lit alley of taverns, thus bridging two very different worlds.

Hozenji Yokocho lane, Osaka. Photo ©JAPAN WEB MAGAZINE

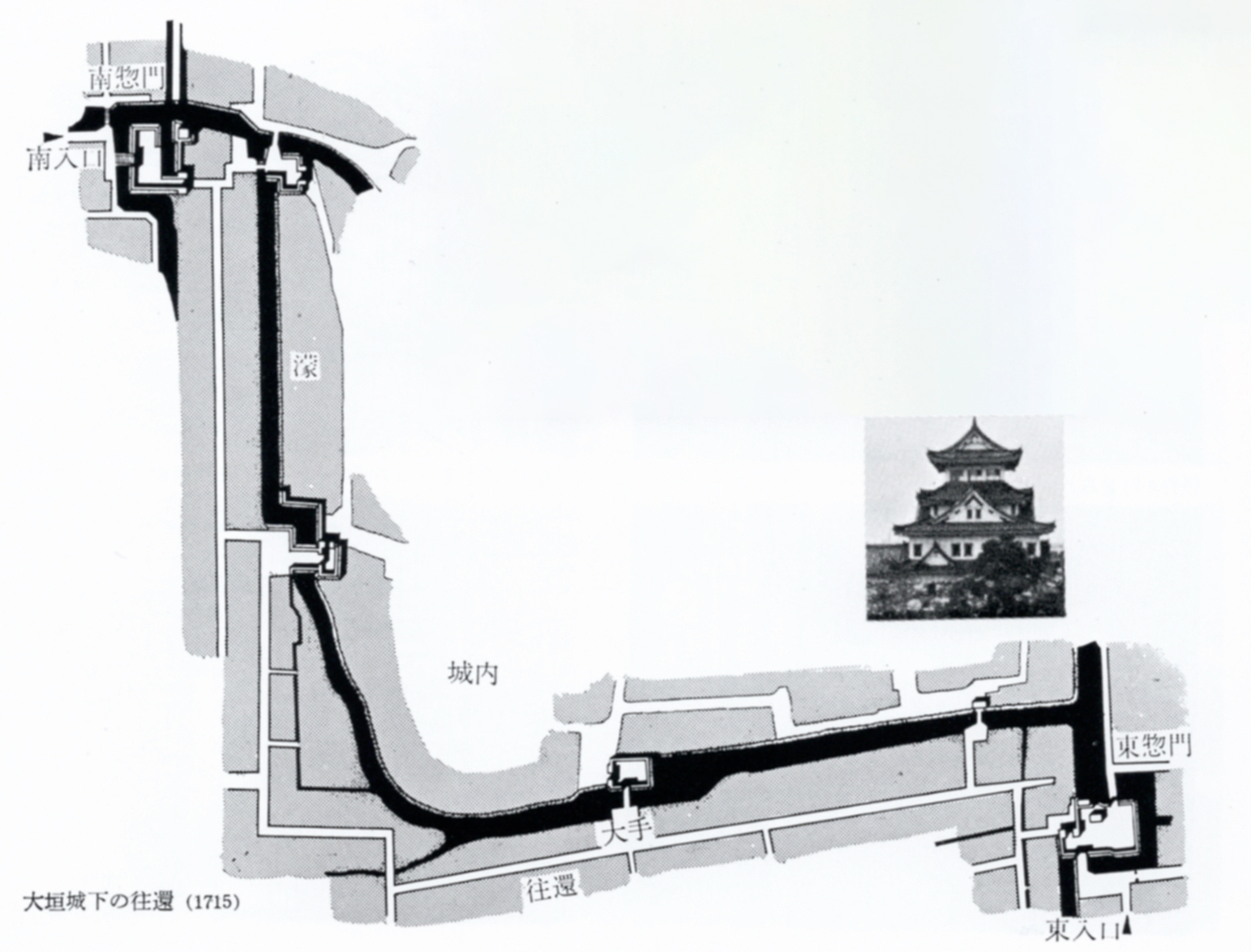

To cite more complicated cases, masugata (box-form) enclosures commonly situated at the entry gates to medieval castles [Ed.: These masugata forced anyone approaching to slow down and change directions under the watchful eye of guardsmen]. In feudal Japan, where the vital lifelines of transportation and communication almost never turned corners in any town’s commercial or residential district, even main thoroughfares always incorporated multiple turns outside castles. Perhaps the most colorful example is the twisted passageway in the castle town of Okazaki, in Aichi prefecture, likened in popular song to the long and convoluted accounts of a brothel madame. Likewise, the route skirting Ogaki Castle in Gifu prefecture took some 17 turns through the center of town between the eastern and southern gates (as shown in the diagram). The principal purpose of these turns was of course military, enabling the easy entrapment of enemies, but they also served to make cities more compact.

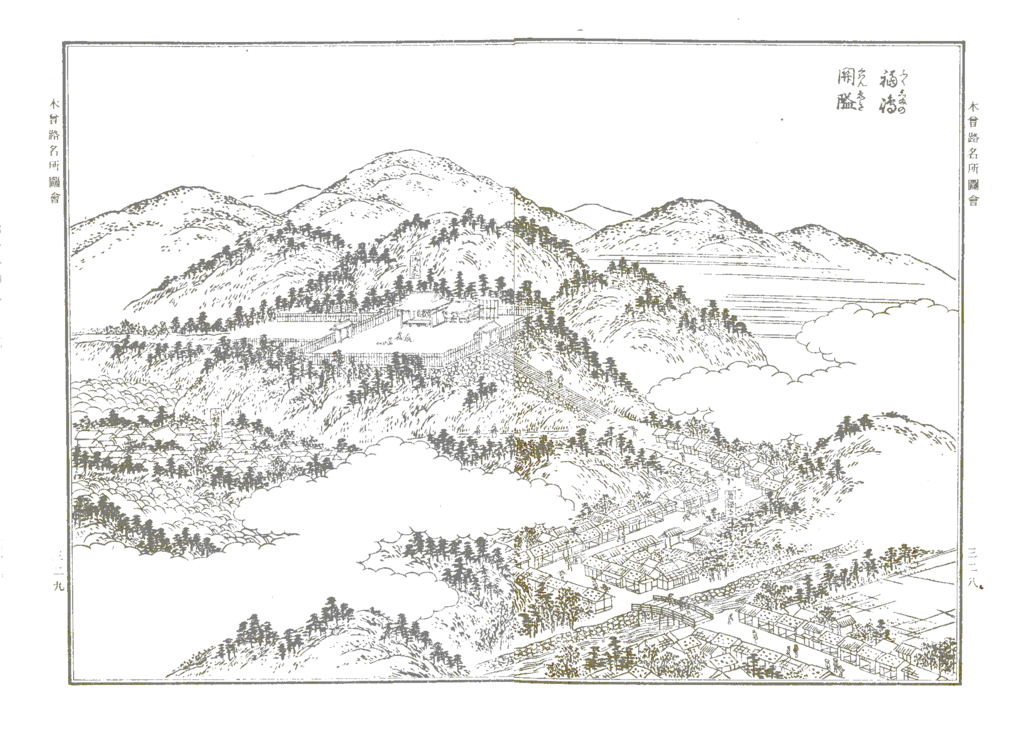

Approach to the Kiso-Fukushima checkpoint, from Akisato Rito, ed., Kisoji meisho zue [pictorial description of noted places on the Kisoji road], 1805

Thoroughfare in the Ogaki castle town made in 1715

Other classic examples of ore-magari include the approaches to Kotohiragu shrine in Kagawa prefecture, the Toshogu mausoleum and Taiyuin temple in Nikko, the Kiyomizu-dera and Ginkakuji temples in Kyoto, or the various temples along the 88-Site Pilgrimage Trail in Shikoku. Each place employs a different scheme of siting the sanctum, but essentially all approaches intentionally twist and turn to interconnect a greater variety of spaces.

Stone steps in Nijo Castle, Kyoto

Ordinarily, in geometry sumi-chigai refers to diagonals, but in the broader context of actual spatial configurations it has come to include oblique formations such as the positioning of the shoin wings of the Katsura Imperial Villa and Nijo Castle. When a line connecting every other corner in a series of buildings shows their basic orientation to be on a bias—i.e., diagonal in direction—that is sumi-chigai.

Shoin wings of the Katsura Imperial Villa, Kyoto. Photo ©alonfloc, CC BY 3.0

The idea of sumi-chigai derives from the spirit of the tea ceremony; the tea master Kobori Enshu was especially known for using it in his many [tea room and utensil] designs. As a method, sumi-chigai offers an advantage in combining elements of different sizes, materials, and shapes with relative ease and to lasting effect. In architecture, it gives each [diagonally aligned] component structure wider views from two sides.

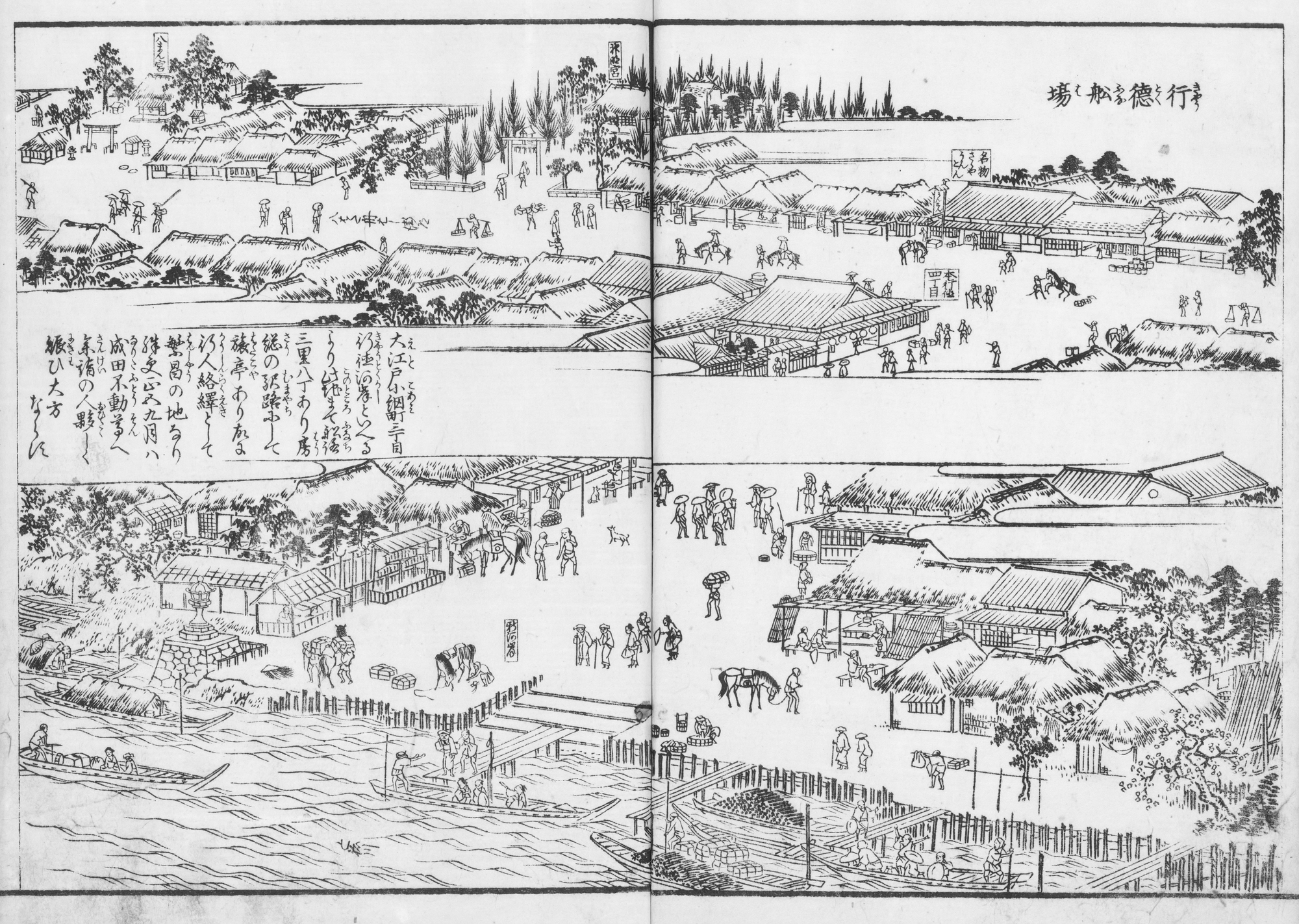

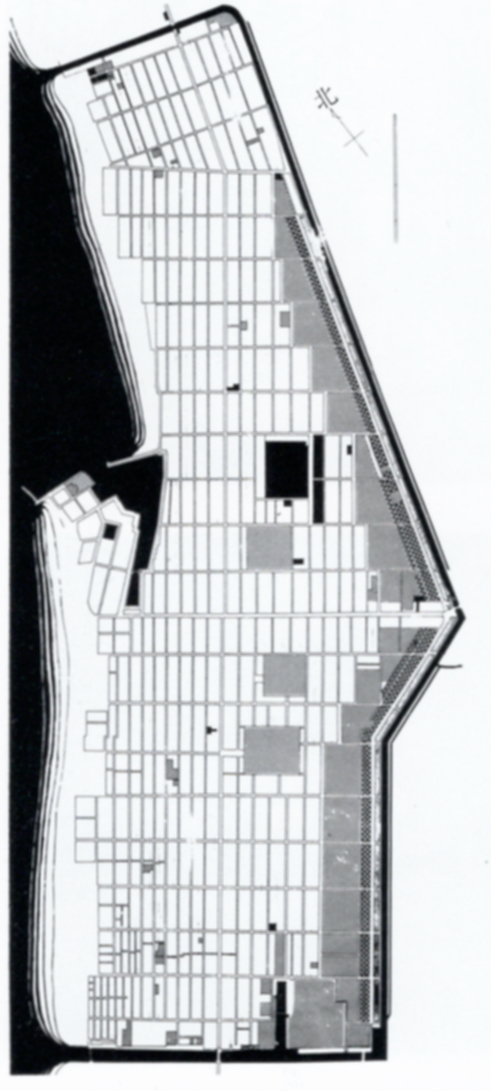

Examples of sumi-chigai on a small scale include the Jukoin temple on the grounds of Daitokuji temple; the southwest corner of the Gojo Bridge; the Inari Shrine at Shichijo-gawara in Kyoto; Nagoya Castle; and the Gyotoku salt boat pier. Or, as a larger example, the sawtooth-shaped 1689 Sakai port embankment in Osaka, whose greater sea frontage provided room for more warehouses and shops, above which the roof of a permanent theater stage soared.

Gyotoku boat pier, from Hasegawa Settan, Edo meisho zue [pictorial description of noted places in Edo], 1834

City plan of Sakai, 1689

Sakai port embankment

Moreover, when used in city planning, sumi-chigai street corners played an important role in shifting [or focusing] the flow of public activities or as highly visible gathering places (kosatsuba) for posting feudal lords’ proclamations.

The ikedori (literally, taking alive) method refers to taking serendipitous advantage of scenic natural beauty such as distant hills and rivers or noteworthy man-made features such as monuments, moats, picturesque villages, pagodas, and the like.

Entsuji temple, Kyoto. Garden and Mt. Hiei in the back. Photo: ©663highland, CC BY-SA 3.0

The well-known shakkei (borrowed landscape) style of Japanese gardens is one such example, although simply establishing a beautiful enclosed space so that it seems to merge with a beautiful outside vista is only part of the scheme. In the strictest sense, the composition of shakkei gardens should follow three precedents drawn from traditional Nihonga painting. The first requires leaving the sky as “unpainted” empty space in the composition, as in the view [over the hedges] to the hills of Iwakura at the Shugakuin Imperial Villa in northern Kyoto. The second makes use of [a mediating middle ground such as] a grove of trees with a view through the trunks to the distant expanse of the hills to act as a bridge to the close-up rock or moss garden, as in the garden at Entsuji temple, also in northern Kyoto. The third involves arranging elements such as a gate or stone lantern beyond the immediately visible space demarcated by a low hedge or wall, thereby laying claim to the further space—even if it belongs to someone else’s garden.

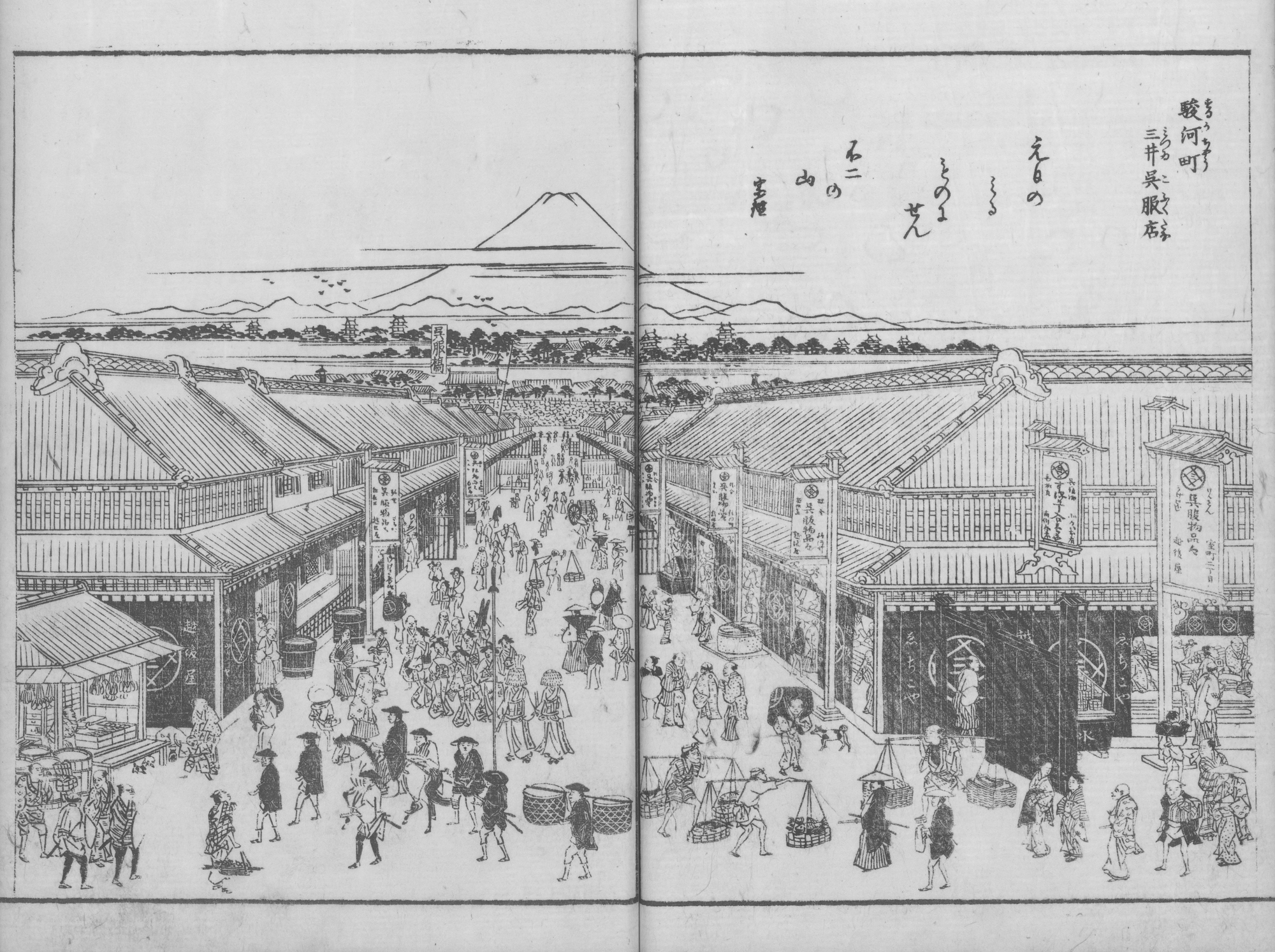

In an urban context, a classic example of ikedori may be found in the old Surugacho-dori promenade in Edo’s Nihonbashi district, where every two-story machiya shophouse had a clear view of Mt. Fuji in the distance. While it is unclear whether this was intentional on the part of the city planners who laid out the avenue at the end of the sixteenth century, the area became famous for its ikedori—in fact, the very name “Surugacho” alluded to Mt. Fuji’s Suruga province. Over the course of the twentieth century, however, tall buildings and smoky air conditions gradually obscured the view.

Surugacho Mitsui Gofukuten, from Hasegawa Settan, Edo meisho zue, 1834. Mt. Fuji is at the end of the sightline from the Surugacho street

The translation of the parts of Nihon no toshi-kukan [Japanese Urban Space] was made possible by courtesy of the publisher. Nihon no toshi-kukan was written by Toshi-dezain kenkyutai [Research Group for Urban Design], edited and published by Shokokusha Publishing Co., Ltd. in 1968.

Some of the photos in this entry were sourced from outside the original book.