Analyzing the Legacy of Olympic-Led Urbanization

Every major Japanese city is crisscrossed by boulevards, those major streets that carry traffic and delineate neighborhoods. But despite their physical prominence, boulevards play little role in the discourse of Japanese urbanism. What does this contradiction imply? Are boulevards unimportant to the experience of the Japanese city, or have they simply been neglected?

When we imagine a Japanese city scene, we are likely to call to mind a quiet residential alley (roji), a narrow shopping street (shotengai), or a secluded shrine. In Paris, by contrast, boulevards are considered defining features not only of the city, but also of the character of its residents. Tomes are devoted to Baron Haussmann’s creation of the boulevards and their social, economic, political, and aesthetic implications. The research that follows argues that Japanese boulevards, also significant public spaces, are worthy of the same close examination.

We have selected and profiled six important Japanese boulevards here for their diversity in scale, function, and composition. These boulevards shape the daily experiences of millions of pedestrians, cyclists, drivers, and transit users. They also provide space for recreation, shopping, public art, and events. The drawings reveal these diverse forms of organization and occupation. They also illustrate how attitudes toward boulevard planning have shifted gradually over time.

From Kyoto’s thousand-year-old Karasuma boulevard to Tokyo’s recently completed Kanni boulevard, this type of infrastructure has gradually become more regimented and dominated by automobiles. But with plans underway for the transformation of Osaka’s Midosuji boulevard, among others, the future of these important urban features is contested. Should boulevards expedite the movement of cars, or should they be repurposed as shared gathering places? This investigation brings boulevards into conversation with other, more recognizable elements of the Japanese cityscape to help influence these important debates.

Utagawa Hiroshige, Sugura-cho, from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1856. Image source: The Brooklyn Museum

Camille Pissarro, Boulevard Montmartre, Spring, 1897. Image source: Google Arts and Culture

Utagawa Hiroshige, Asakusa Ricefields and Torinomachi Festival, from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1856. Image source: The Brooklyn Museum

Gustave Caillebotte, Man on a Balcony, Boulevard Haussmann, 1880. Image source: ArtStor

In the nineteenth century, boulevards played a role in defining the cultural and civic life of Edo (now Tokyo) and Paris, two metropolises of the early modern world. Representations of both cities in art give us a sense of how urban space influenced the subjectivity of their inhabitants. From the secure confines of the voyeur’s perch, one can watch the bustle of modern life unfold on the boulevards below. In Utagawa Hiroshige’s view of Suruga-cho, pedestrians dominate the scene. In Camille Pissarro’s painting of Boulevard Montmartre, by contrast, much of the street is occupied by speeding carriages, appearing closer to the car-controlled boulevards of today.

Part of Kyoto’s original street grid established in 794 CE, Karasuma-dori boulevard was widened in the early Meiji era when it became the main north-south axis leading to Kyoto’s train station. The otherwise straight road swerves to preserve the entry to Higashi-Honganji, an important temple complex.

Although generous by nineteenth-century standards, Karasuma-dori is narrow compared to more recently planned boulevards, leaving little room for pedestrians and cyclists. The Kyoto Municipal Subway Karasuma Line, opened in 1981, passes below it.

A seventeenth-century street developed west of Osaka’s medieval castle, Midosuji boulevard was widened when Osaka’s first subway line was installed beneath it in the early 1930s. The street and the subway line connect Umeda and Namba, the city’s two largest transportation hubs.

More than most Japanese boulevards, Midosuji boulevard plays a strong role in Osaka’s civic imagination thanks to its broad sidewalks, art installations, and mature ginkgo trees.

Hokkaido’s relatively sparse population in the late nineteenth century made it a laboratory for Japan’s nascent urban planning profession. Like other green space in central Sapporo, O-dori Park exemplifies this through its Beaux-Arts-influenced axiality and symmetry. Partially established as a flower garden in 1879, the park approached its current form in 1909.

O-dori Park is divided into lawns, plazas, and planted areas punctuated by public art, monuments, and the iconic Sapporo TV Tower. Cars play a secondary role here, but the Tozai Subway Line stops twice along the length of the park.

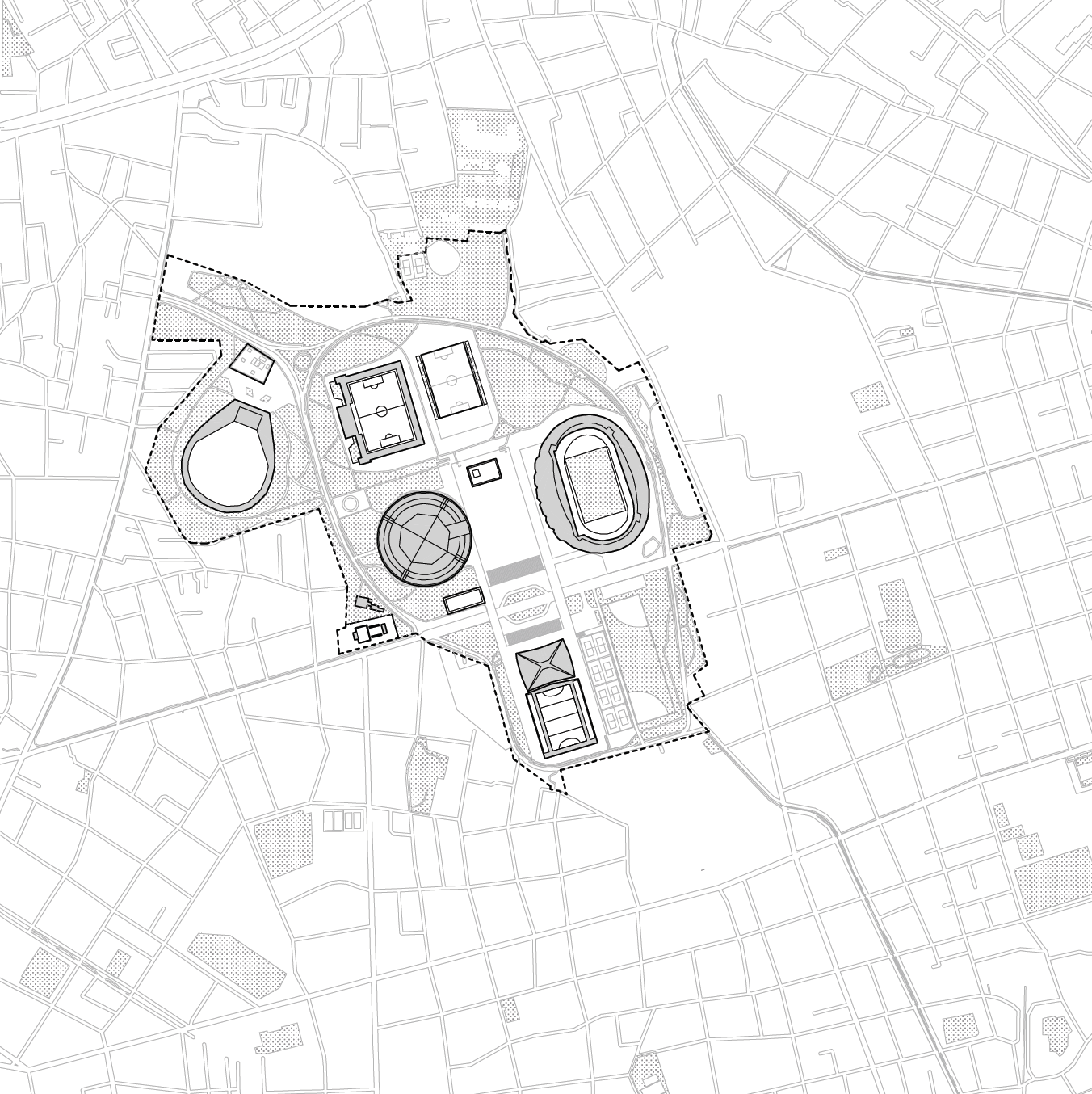

The planning of Hiroshima’s Heiwa O-dori, or “Peace Boulevard,” began in 1946, soon after the city’s devastation in WWII. It runs between Hijiyama Park and Nishi-Hiroshima station while a spur, Ekimae-dori street, leads to the city’s main train terminal. Kenzo Tange’s Peace Memorial Park and Museum is the centerpiece of the boulevard. Sculptor Isamu Noguchi designed the railings on the bridges leading to the park at Tange’s invitation.

In addition to eight traffic lanes and broad sidewalks, the 100-meter-wide boulevard contains sinuous paths dotted with public art. Faster traffic is divided from peripheral feeder streets by an undulating landscape of hillocks and berms, some with rocks and plantings referencing traditional Japanese gardening.

Yokohama’s O-dori Park, a later variation on the theme established by Sapporo, was built in 1973 on land reclaimed from an inlet on Tokyo Bay. The street is part of a chain of spaces that leads from the waterfront and civic center to neighborhoods further inland.

Yokohama’s O-dori Park is actively programmed with play structures, plazas, and public restrooms. Like many of its predecessors, the park sits on top of a train line, the Yokohama Municipal Subway Blue Line.

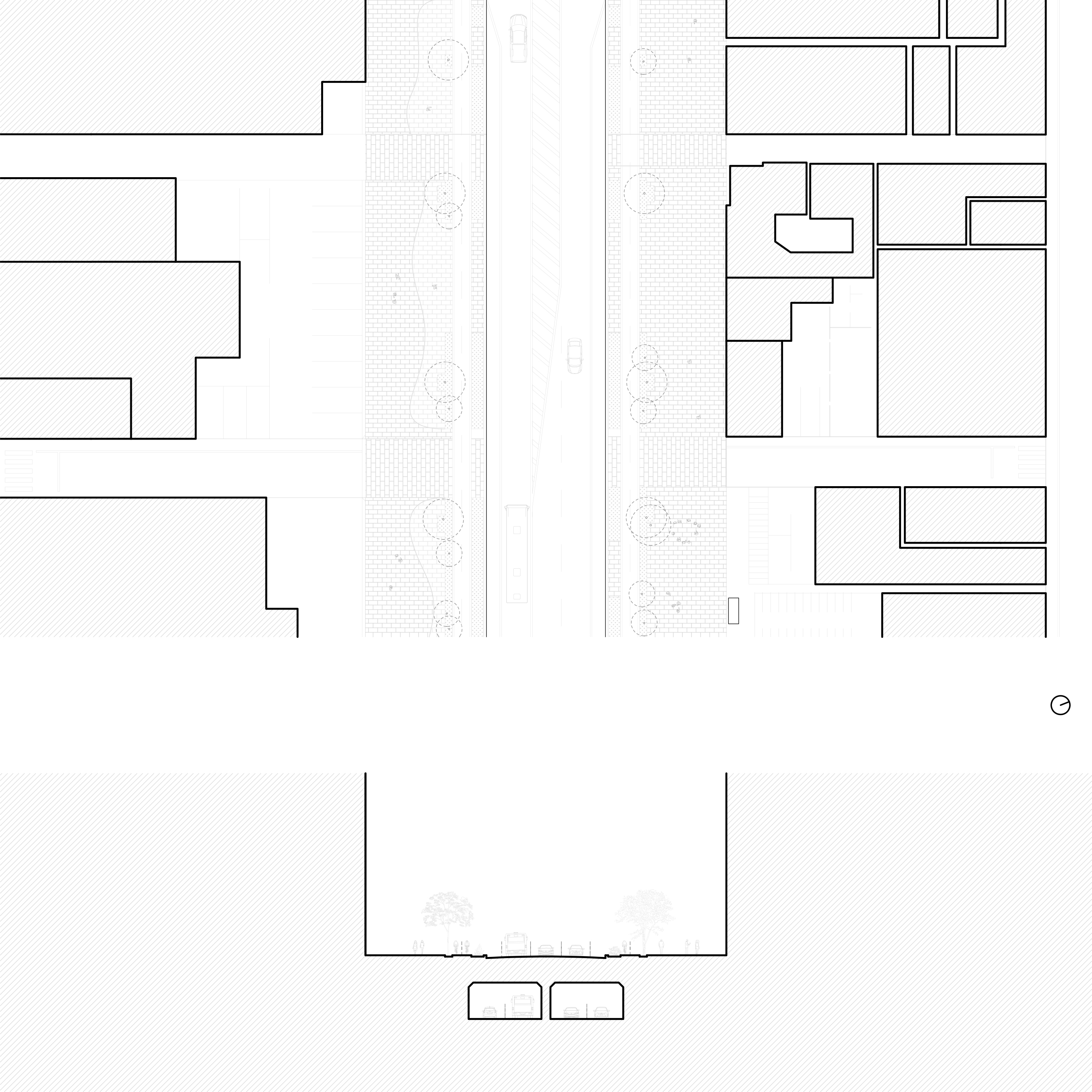

Kanni-dori was completed in 2019, completing a major link in the city’s road network at the expense of many demolished buildings and blocks. Some of the traffic on Kanni-dori is diverted into a tunnel which runs beneath Toranomon Hills, a major urban redevelopment project undertaken by Mori Building.

Billed by Mori Building as Tokyo’s answer to the Champs-Élysées, the stretch of Kanni-dori to the east of Toranomon Hills features generous sidewalks and four bike lanes. The older buildings that surround the site have not yet had time to reorient themselves to the street, leaving many irregular open spaces occupied by pop-up shops and restaurants. This diversity of fabric is unlikely to remain, as contiguous plots are consolidated for additional high-rise development.