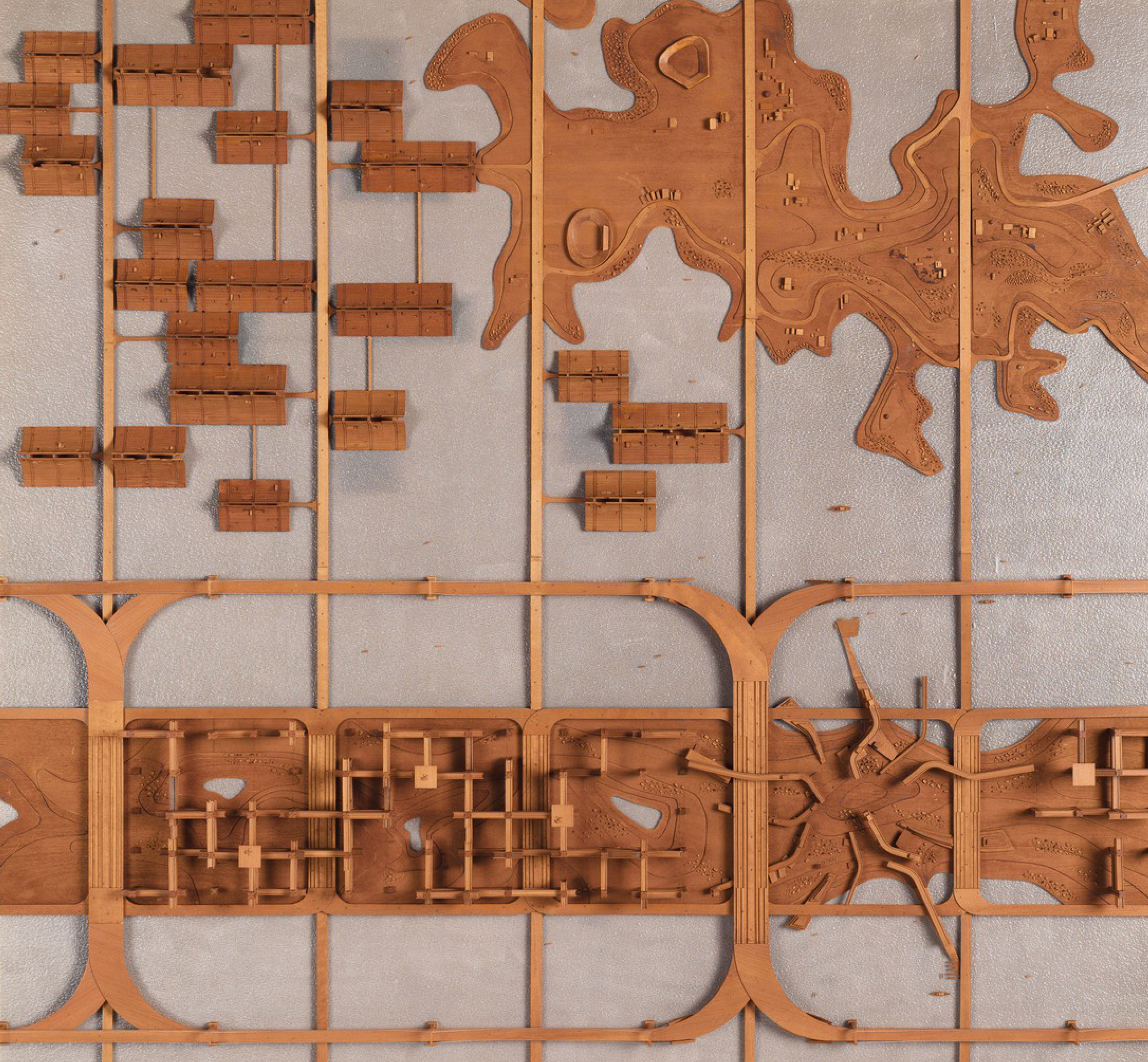

Photographer Naoya Hatakeyama on the Act of “Tracing Lines”

Naoya Hatakeyama, Tracing Lines/Yamate-Dori #3418, 2008. Courtesy of the photographer and Taka Ishii Gallery

Tracing Lines

Unlike what Mother Nature creates, what mankind creates has a reason. There are a variety of human reasons such as comfortableness, efficiency, convenience, or rights. The ultimate reason is to enable ourselves to lead a better life. For the time being, something is devised to overcome the immediate hardships.

There are many places on this earth where such human reasons have been provided with three-dimensional form and emerge in overwhelming quantity. As the overall quantity of the forms that have emerged is so absurd in such places, it seems absolutely impossible to consider the individual names or history of the people who had something to do with the emergence of a certain form despite the fact that, like me, each one of them has been leading a life of his or her own. Staring at that expanse in bewilderment, I feel as if I am conversely being deprived of my own name and abstracted into the collective “human being.” The site where we undergo such experiences is called a city.

Looking at a city, it is hard to believe that the massive lines, planes, and colors covering my field of vision are decided entirely and to the minutest detail by human beings. At the same time, I imagine the exorbitant number of reasons or plans—i.e., invisible thoughts—that must have existed prior to their embodiment as visible forms.

In the process of a thought being embodied as a form, no doubt the hands of countless persons drew lines on a piece of white paper. In order to lead a better life, in order to overcome an immediate hardship, human beings must have imagined the ideal form and tried drawing many a line. All the lines I see in the actual city are based on lines drawn in such a way. The lines in the city, however minute they may be, must all be filled with a human volition.

If I want to call the city I live in my home one day, it would be necessary to imagine the human volition entrusted in the lines composing that city and decipher the rich metaphor included there. A metaphor provides the opportunity for me to correspond with the outside world and is the great force that connects me with the environment. If I miss that, all that comes coldly to the surface from the view of the city are the collective shadows of “desire” and “unconsciousness.” I probably would not be able to call such a place my home.

I recall Takagi Jinzaburo, whose death in 2000 was mourned by many people. Although he was originally an experimental scientist who did nuclear research, after leaving university, he made a complete change and devoted the rest of his life to antinuclear activities. No other Japanese has ever thought over so thoroughly the relationship between people living in the present age of science and technology and the natural environment. He used to say that particularly when he was not feeling good on his sickbed, he found the artificial lines and planes around him unbearably loathsome. This comment left an indelible impression on me.

The window frame, the curtain rail, smooth glass, the joint where the wall and the ceiling meet, the edge and wall of the opposite building, the windows cut through there with regularity, the water tower and antenna on the roof, the power lines traversing in midair—such lines drawn by the human hand appeared unbearably loathsome to his exhausted eyes. On such occasions, his eyes kept wishing for organic lines and planes that continued to change all the time. He would search for trees, bushes, plants, water, the clouds and birds in the sky, or the mountains.

When a person on his deathbed has reached the limit of the severity of looking at things and says everything is “unbearably loathsome,” those words should contain the truth of a human being as a dying creature. Why don’t the lines and planes in the urban artifacts that were supposed to have been created to “improve life” make a person in his last moments happy? Why do visual metaphors equal to the things in nature appear nonexistent in the city? Do we have to die unable to regard the city as our home? Those of us living in the city should begin considering these issues immediately.

I do not know how far I can get involved in such a hard problem as a photographer. Some people may say, “A photographer can just keep praising the beauty of nature.” However, to a photographer who has already decided to focus on cities, such a comment is to no avail. A poster of a natural landscape hung in a sickroom may provide temporary comfort to someone in his death hours, but that too is part of the city and not real nature.

Go and look for lines that would serve as metaphors in the city. Aren’t the photographs I take supposed to function as a “pencil of nature”? Therefore, I shall begin by retracing the lines in the city with this pencil. There, I should come across double lines that both the pencils drawn by the human being and by nature have traced. Somewhere along that double line, something that had been concealed until then may appear and allow us to find a clue to a metaphor that would lead us to the entrance of our home. I shall use this pencil in search of that possibility.

The pencil I am holding is naively honest. That can’t be helped because that is the strong point of nature. Using this pencil, I recall the days when, long ago, I stopped drawing in an offhand manner and did so carefully for the first time, or when I placed a thin sheet of paper atop a picture or photograph I fancied and traced its lines. I found the perspective my hands reproduced almost automatically on the paper exciting. However, the adults who recognize a grand freedom in a child’s picture and praise it would probably look at the lines I drew and regret that art had disappeared from yet another child.

Indeed, at that point, I became incapable of understanding what it meant to “draw a picture freely.” I felt I had become an unexciting person, and the word “freedom" had suddenly changed into an obsession. Quite a while afterward, my encounter with this naively honest pencil, namely photography, set me free from that complex feeling. Like what the grown-ups regard as “art,” this pencil proved to be a tool to head toward the metaphor. However, as it proceeds via nature, the reality was simply not so easy to recognize. I realized that there are many people in this world who spend their lives simply tracing lines and that that is a hard job.

A photograph always indicates a message of some sort from nature’s side. At least, I believe so. If I continue to trace the lines in the city bearing that in mind and hold discussions based on what appears there, in due course, considerate people should appear and begin to draw new lines overcoming the present lines in the city and lines fit to become rich metaphors equal to things in nature.

As I walk along dreaming of such a future city, on the other hand, I have to consider simultaneously the question of urbanization that is happening to the pencil I am holding in my hand. For “human reasons,” such as efficiency and convenience, the naive honesty of nature is being abandoned by means of high technology. My pencil is beginning to undergo the same process in which the city was formed. Can a photographer call this new pencil his home? The difficulties are becoming even more complicated. There is a lot to be done.

This essay originally appeared in HATAKEYAMA NAOYA: Draftsman’s Pencil, published in 2007 by the Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura and Hayama, coinciding with the exhibition at the museum.

- Naoya Hatakeyama is a photographer based in Tokyo. Before completing postgraduate studies at the University of Tsukuba, he had his first solo exhibition, “Contour Line,” at Zeit-Foto Salon in Tokyo in 1983. Since then his work has been shown internationally, including Lime Works (1991–94), River Series (1993–94), Blast (1998–2005), Underground/Water (1998–99), Kesengawa (2002–03), Slow Glass/Tokyo (2006–09), Scales (2008), Tracing Lines/Yamate-Dori (2008–09), Ciel Tombé (2009), Terrils (2009–10), and Rikuzentakata 2011–2016. In 1997 he received the prestigious Kimura Ihei Memorial Photography Award. Sited in a variety of situations around the world, his work explores the relationship between nature, the city, and photography. His photographs are found in public collections including the National Museum of Modern Art Tokyo, Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA), MoMA, the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, the Swiss Foundation for Photography, La Maison Européenne de la Photographie, the Tate, and the Victoria & Albert Museum. Publications of his work include Naoya Hatakeyama: Excavating the Future City (coauthor, Aperture, 2018) and Zeche Westfalen I/II Ahlen (Nazraeli Press, 2006).