Social Brewery

Can Tokyo be a cultural city- a city that is cognizant of the “metabolic rift”– the often-inevitable environmental degradation that accompanies urbanization- and yet committed to confronting and even repairing it? Can it seek and imagine an alternative strategy- an architecture- that is more attuned to the nuances of relations between the social and natural worlds, and between scales and typologies of construction?

The proliferation of large urban developments in Tokyo demonstrates the increasing privatization of the public domain and of public life. Roppongi Hills, Tokyo Midtown, Toranomon Hills, COREDO Muromachi, and Azabudai Hills, are among the completed mega projects by a handful of big developers that are rapidly and dramatically changing the urban landscape of the city.

The consumerist culture embedded in these technically accomplished and often lavishly made privately owned public spaces can be alluring. But they can also be exclusionary- and challenging for the public to occupy and use with the same degree of freedom that they would a city street. Despite their thermal comfort and irresistible charm, these developments, seem to blatantly defy Henri Lefebvre’s slogan and argument for “the right to the city”, and its implied erasure of social and spatial inequity.

The work of the option studio shown in this report explored an alternative strategy. One based on the simultaneous choreography of a multitude of architectural ideas and interventions- of different scales and typologies- hybrids- that represent the needs and desires of Tokyoites to live together. Our intention is to shift the emphasis in contemporary development from the economies of scale to the economies of scope- an approach, characterized by diversity and variety rather than volume.

The location for the projects was a series of urban sites close to Ueno, and the public park that was established in the 19th century. The park contains several museums and cultural institutions, including the city’s zoo and the National Museum of Western Art, the only building by Le Corbusier in Japan. The area also encompasses two of Tokyo’s foremost academic institutions, the University of Tokyo, and Tokyo University of the Arts.

The site of investigation by the studio was the urban spine connecting these institutions to the nearby neighborhood of Yanesen. The framing of the programs took into consideration a diversity of topics, including culture and the everyday, the changes in the demography of Tokyo, the needs of young and old, housing, migrant workers, the student population, health and wellbeing, recycling of artifacts, new spaces of work, the future consequences of degrowth, as well as alternative conceptions of the relation between architecture and nature.

If Ueno Park represents the 19th century vision of culture/nature how can the phenomenon be reconceptualized today? How can architecture’s situatedness within a broader environmental agenda help structure our contemporary projects? To achieve this task, the student were encouraged to select their own site and program with the aim of designing an architectural intervention or ensemble that would reconsider and question the role of scale and typology as a means of enhancing the quality of life of the district.

The studio traveled to Tokyo in February 2024 and spent a week visiting the study area. The trip to Tokyo was organized in conjunction with the Loeb program at the GSD. All nine Loeb fellows and two administrators accompanied the studio to Japan. This collaboration added a richness to the conversations during the trip.

Professor Shunya Yoshimi an authority on the evolution of Tokyo conducted a tour of Ueno Park and the surrounding areas. The studio also visited Tokyo University of the Arts, where Professor Mitsuhiro Kanada, a structural engineer, and Professor Tom Heneghan provided presentations on the institution and the history of contemporary architecture in Japan. Professor Yusuke Obuchi conducted a similar visit to the campus of the University of Tokyo. Kayoko Ota was able to provide further insights and guidance both prior and during the visit to Tokyo. Other highlights included conversations with Toyo Ito and other architects as well as presentations at Takenaka’s headquarters.

Yanesen- provides a contrast in scale and character to Ueno. Mitsuyoshi Miyazaki, is an architect who has devoted a major portion of his practice to the regeneration of the area where he lives and works as an architect and an entrepreneur. Mr. Miyazaki gave a talk for both the studio and Loeb fellows on the topic of urban regeneration. He and his colleagues also showed us the neighborhood, including several of their design projects.

During our stay in Japan, we also organized an afternoon conference led by Professor Yoshimi on emergent issues in contemporary Japanese society. The event included the participation of several GSD alumni and friends who were able to provide further insights in response to the students’ initial design ideas. Throughout the semester we paid special attention to the relationship between design development and structural and construction challenges of each design. We were fortunate to have several interactions with Professor Mitsuhiro Kanada on the structure of each of the building proposals. Some of the comments on the projects by Professor Kanada are showing in the report.

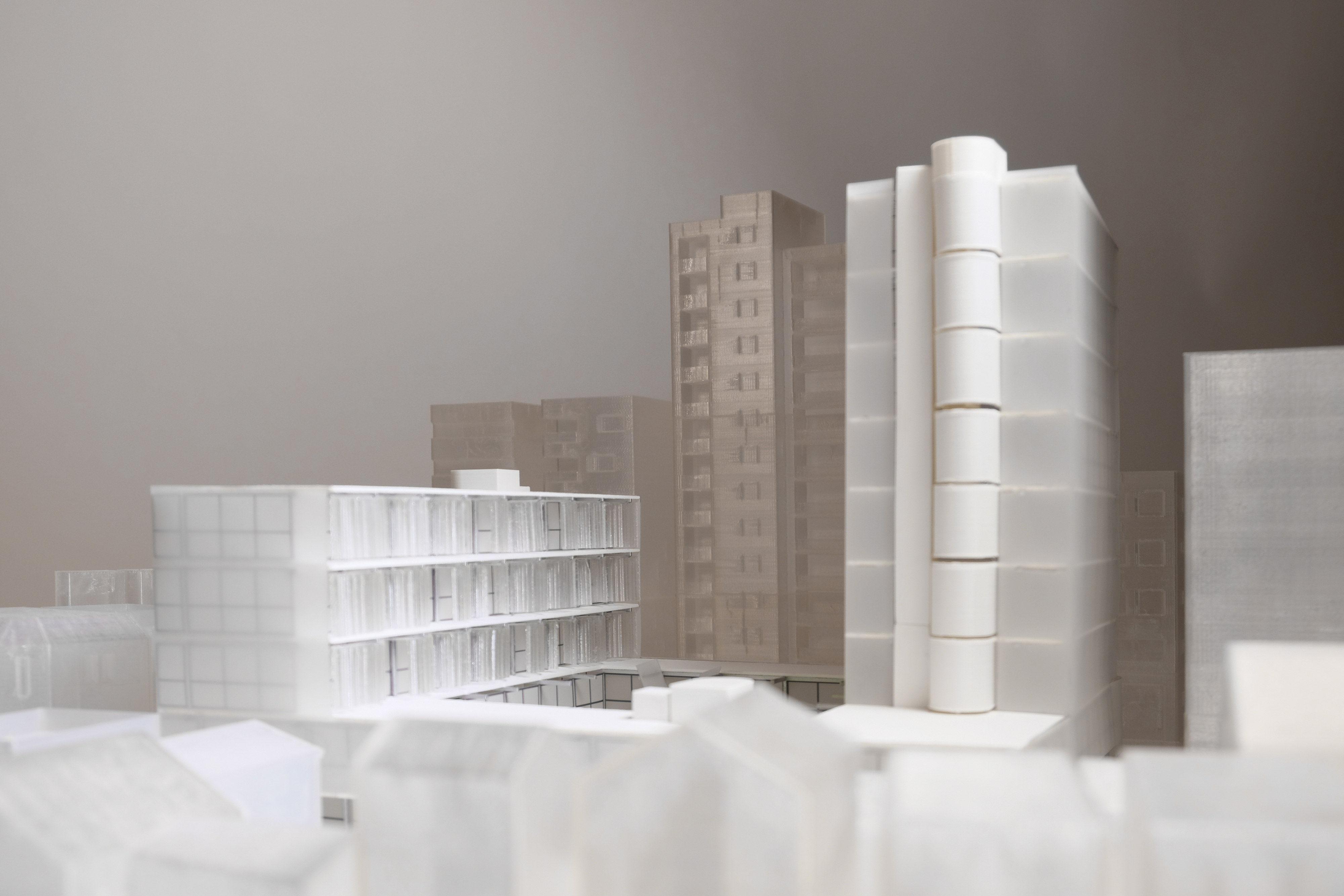

In reviewing these proposals what is important to consider is the fact that each project or sub-project is intended simultaneously as an independent and autonomous architectural artifact and yet also exists as part of a collective. The tension between the singular and the plural is represented by the drawings and models of each project as well as the larger scale maps and models that register the idea of an urban ensemble. This process is less deterministic than traditional urban design but still requires many considerations, conversations, and adjustments to programmatic and spatial qualities of each proposal. The outcome is an architecture of the city developed in response to the needs of the district and developed as part of a network of connections with the existing fabric of the city. The juxtaposition between old and new, as well as modified parts of the neighborhood produce a multiplicity of affiliations and associations, including forms of diversity, that stand in contrast to the wholesale erasure and rebuilding of the city so prevalent in contemporary development. Perhaps the outcome can also demonstrate the viability of Tokyo as a cultural city.